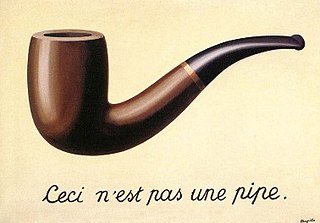

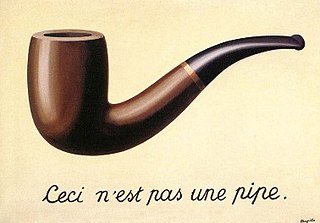

René François Ghislain Magritte was a Belgian surrealist artist known for his depictions of familiar objects in unfamiliar, unexpected contexts, which often provoked questions about the nature and boundaries of reality and representation. His imagery has influenced pop art, minimalist art, and conceptual art.

Surrealism is an art and cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists aimed to allow the unconscious mind to express itself, often resulting in the depiction of illogical or dreamlike scenes and ideas. Its intention was, according to leader André Breton, to "resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality", or surreality. It produced works of painting, writing, theatre, filmmaking, photography, and other media as well.

Chloe Anthony Wofford Morrison, known as Toni Morrison, was an American novelist and editor. Her first novel, The Bluest Eye, was published in 1970. The critically acclaimed Song of Solomon (1977) brought her national attention and won the National Book Critics Circle Award. In 1988, Morrison won the Pulitzer Prize for Beloved (1987); she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1993.

The Beat Generation was a literary subculture movement started by a group of authors whose work explored and influenced American culture and politics in the post-World War II era. The bulk of their work was published and popularized by Silent Generationers in the 1950s, better known as Beatniks. The central elements of Beat culture are the rejection of standard narrative values, making a spiritual quest, the exploration of American and Eastern religions, the rejection of economic materialism, explicit portrayals of the human condition, experimentation with psychedelic drugs, and sexual liberation and exploration.

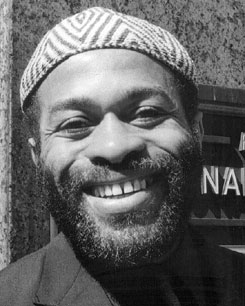

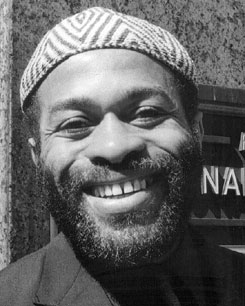

Theodore Joans was an American jazz poet, surrealist, trumpeter, and painter, who from the 1960s spent periods of time travelling in Europe and Africa. His work stands at the intersection of several avant-garde streams and some have seen in it a precursor to the orality of the spoken-word movement. However, he criticized the competitive aspect of "slam" poetry. Joans is known for his motto: "Jazz is my religion, and Surrealism is my point of view". He was the author of more than 30 books of poetry, prose, and collage, among them Black Pow-Wow, Beat Funky Jazz Poems, Afrodisia, Jazz is Our Religion, Double Trouble, WOW and Teducation.

Aimé Fernand David Césaire was a Francophone Martinican poet, author, and politician. He was "one of the founders of the Négritude movement in Francophone literature" and coined the word négritude in French. He founded the Parti progressiste martiniquais in 1958, and served in the French National Assembly from 1945 to 1993 and as President of the Regional Council of Martinique from 1983 to 1988.

The Chicago Surrealist Group was founded in Chicago, Illinois, in July 1966 by Franklin Rosemont, Penelope Rosemont, Bernard Marszalek, Tor Faegre and Robert Green after a trip to Paris in 1965, during which they were in contact with André Breton. Its initial members came from far-left or anarchist backgrounds and had already participated in groups IWW and SDS; indeed, the Chicago group edited an issue of Radical America, the SDS journal, and the SDS printshop printed some of the group's first publications.

Penelope Rosemont is a visual artist, writer, publisher, and social activist who attended Lake Forest College. She has been a participant in the Surrealist Movement since 1965. With Franklin Rosemont, Bernard Marszalek, Robert Green and Tor Faegre, she established the Chicago Surrealist Group in 1966. She was in 1964-1966 a member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), commonly known as the Wobblies, and was part of the national staff of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in 1967-68. Her influences include Andre Breton and Guy Debord of the Situationist International, Emma Goldman and Lucy Parsons.

Raymond Georges Yves Tanguy, known as just Yves Tanguy, was a French surrealist painter.

Négritude is a framework of critique and literary theory, mainly developed by francophone intellectuals, writers, and politicians in the African diaspora during the 1930s, aimed at raising and cultivating "Black consciousness" across Africa and its diaspora. Négritude gathers writers such as sisters Paulette and Jeanne Nardal, Martinican poet Aimé Césaire, Abdoulaye Sadji, Léopold Sédar Senghor, and Léon Damas of French Guiana. Négritude intellectuals disavowed colonialism, racism and Eurocentrism. They promoted African culture within a framework of persistent Franco-African ties. The intellectuals employed Marxist political philosophy, in the Black radical tradition. The writers drew heavily on a surrealist literary style, and some say they were also influenced somewhat by the Surrealist stylistics, and in their work often explored the experience of diasporic being, asserting one's self and identity, and ideas of home, home-going and belonging.

The Black Arts Movement (BAM) was an African American-led art movement that was active during the 1960s and 1970s. Through activism and art, BAM created new cultural institutions and conveyed a message of black pride. The movement expanded from the incredible accomplishments of artists of the Harlem Renaissance.

Yvan Goll was a French-German poet who was bilingual and wrote in both French and German. He had close ties to both German expressionism and to French surrealism.

Beloved is a 1987 novel by American novelist Toni Morrison. Set in the period after the American Civil War, the novel tells the story of a dysfunctional family of formerly enslaved people whose Cincinnati home is haunted by a malevolent spirit. The narrative of Beloved derives from the life of Margaret Garner, a slave in the slave state of Kentucky who escaped and fled to the free state of Ohio in 1856.

Afro-Caribbean people or African Caribbean are Caribbean people who trace their full or partial ancestry to Africa. The majority of the modern Afro-Caribbean people descend from the Africans taken as slaves to colonial Caribbean via the trans-Atlantic slave trade between the 15th and 19th centuries to work primarily on various sugar plantations and in domestic households. Other names for the ethnic group include Black Caribbean, Afro or Black West Indian or Afro or Black Antillean. The term Afro-Caribbean was not coined by Caribbean people themselves but was first used by European Americans in the late 1960s.

Amiri Baraka, previously known as LeRoi Jones and Imamu Amear Baraka, was an American writer of poetry, drama, fiction, essays, and music criticism. He was the author of numerous books of poetry and taught at several universities, including the University at Buffalo and Stony Brook University. He received the PEN/Beyond Margins Award in 2008 for Tales of the Out and the Gone. Baraka's plays, poetry, and essays have been described by scholars as constituting defining texts for African-American culture.

100 Greatest African Americans is a biographical dictionary of one hundred historically great Black Americans, as assessed by Temple University professor Molefi Kete Asante in 2002. A similar book was written by Columbus Salley. First published in 1992, Salley's book is titled The Black 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential African-Americans, Past and Present.

20th-century Western painting begins with the heritage of late-19th-century painters Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and others who were essential for the development of modern art. At the beginning of the 20th century, Henri Matisse and several other young artists including the pre-cubist Georges Braque, André Derain, Raoul Dufy and Maurice de Vlaminck, revolutionized the Paris art world with "wild", multi-colored, expressive landscapes and figure paintings that the critics called Fauvism. Matisse's second version of The Dance signified a key point in his career and in the development of modern painting. It reflected Matisse's incipient fascination with primitive art: the intense warm color of the figures against the cool blue-green background and the rhythmical succession of the dancing nudes convey the feelings of emotional liberation and hedonism.

For a history of Afro-Caribbean people in the UK, see British African Caribbean community.

Suzanne Césaire, born in Martinique, an overseas department of France, was a French writer, teacher, scholar, anti-colonial and feminist activist, and Surrealist. Her husband until 1963 was the poet and politician Aimé Césaire.

Tropiques was a quarterly literary magazine published in Martinique from 1941 to 1945. It was founded by Aimé Césaire, Suzanne Césaire, and other Martinican intellectuals of the era, who contributed poetry, essays, and fiction to the magazine. While resisting the Vichy-supported government that ruled Martinique at the time, the writers commented on colonialism, surrealism, and other topics. André Breton, the French leader of surrealism, contributed to the magazine and helped turn it into a leading voice of surrealism in the Caribbean.