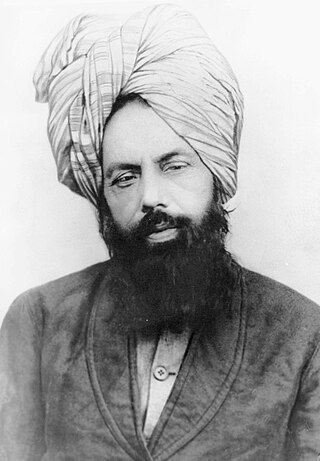

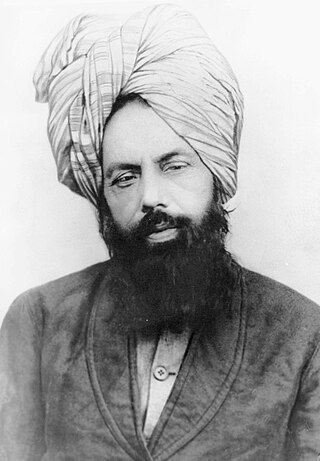

Mirza Ghulam Ahmad was an Indian religious leader and the founder of the Ahmadiyya movement in Islam. He claimed to have been divinely appointed as the promised Messiah and Mahdī—which is the metaphorical second-coming of Jesus (mathīl-iʿIsā), in fulfillment of the Islamic prophecies regarding the end times, as well as the Mujaddid of the 14th Islamic century.

Ahmadiyya Islam considers Jesus (ʿĪsā) as a mortal man, entirely human, and a prophet of God born to the Virgin Mary (Maryam). Jesus is understood to have survived the crucifixion based on the account of the canonical Gospels, the Qurʾān, hadith literature, and revelations to Mirza Ghulam Ahmad. Having delivered his message to the Israelites in Judea, Jesus is understood to have emigrated eastward to escape persecution from Judea and to have further spread his message to the Lost Tribes of Israel. In Ahmadiyya Islam, Jesus is thought to have died a natural death in India. Jesus lived to old age and later died in Srinagar, Kashmir, and his tomb is presently located at the Roza Bal shrine.

The Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement for the Propagation of Islam, is a separatist group within the Ahmadiyya movement that formed in 1914 as a result of ideological and administrative differences following the demise of Hakim Nur-ud-Din, the first Caliph after Mirza Ghulam Ahmad. Members of the Lahore Ahmadiyya movement are referred to by the majority group as ghayr mubāyi'īn and are also known colloquially as Lahori Ahmadis.

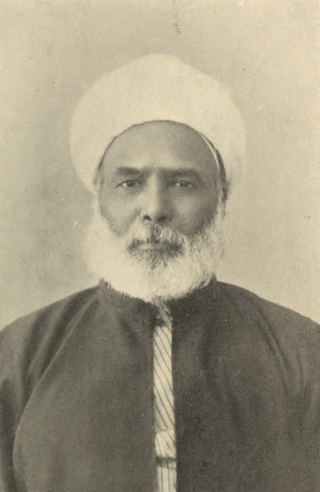

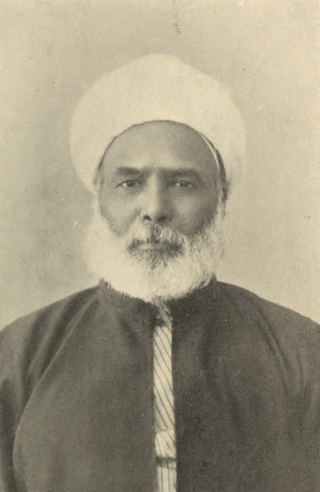

Muḥammad ʿAbduh was an Egyptian Islamic scholar, judge, and Grand Mufti of Egypt. He was a central figure of the Arab Nahḍa and Islamic Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

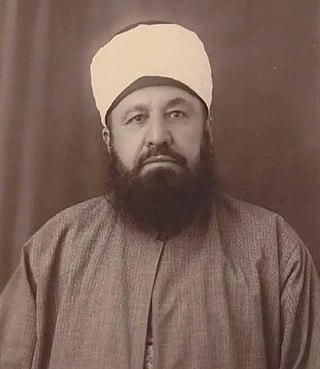

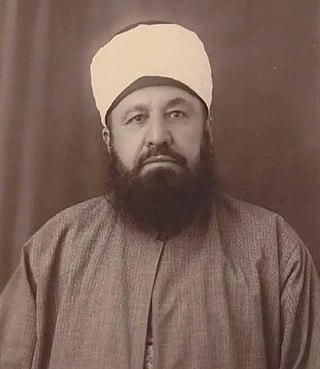

Muhammad Rashid Rida was a prominent early Salafist Sunni Islamic scholar, reformer, theologian, and Islamic revivalist. As a Salafi scholar who called for the revival of hadith studies and a theoretician of an Islamic state, Riḍā condemned the rising currents of secularism and nationalism across the Islamic world following the abolition of the Ottoman sultanate and championed a global pan-Islamist program aimed at re-establishing an Islamic caliphate.

Al-Manār, was an Islamic magazine, written in Arabic, and was founded, published and edited by Rashid Rida from 1898 until his death in 1935 in Cairo, Egypt. The magazine championed the superiority of Islamic religious system over other ideologies and was noteworthy for its campaigns for the restoration of a pan-Islamic Caliphate.

The Roza Bal, Rouza Bal, or Rozabal is a shrine located in the Khanyar quarter in downtown area of Srinagar in Kashmir, India. The word roza means tomb, the word bal mean place. Locals believe a sage is buried here, Yuz Asaf, alongside another Muslim holy man, Mir Sayyid Naseeruddin.

Muhammad Abu Zahra, (1974-1898) was an Egyptian public intellectual and an influential Hanafi jurist. He occupied a number of positions; he was a lecturer of Islamic law at Al-Azhar University and a professor at Cairo University. He was also a member of the Islamic Research Academy. His works include Abu Hanifa, Malik and al-Shafi'i.

Mirza Nasir Ahmad was the third Caliph of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. He was elected as the third successor of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad on 8 November 1965, the day after the death of his predecessor and father, Mirza Basheer-ud-Din Mahmood Ahmad.

Mirza Basheer-ud-Din Mahmood Ahmad was the second caliph, leader of the worldwide Ahmadiyya Muslim Community and the eldest son of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad from his second wife, Nusrat Jahan Begum. He was elected as the second successor of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad on 14 March 1914 at the age of 25, the day after the death of his predecessor Hakim Nur-ud-Din.

Islamic modernism is a movement that has been described as "the first Muslim ideological response to the Western cultural challenge," attempting to reconcile the Islamic faith with modern values such as democracy, civil rights, rationality, equality, and progress. It featured a "critical reexamination of the classical conceptions and methods of jurisprudence", and a new approach to Islamic theology and Quranic exegesis (Tafsir). A contemporary definition describes it as an "effort to re-read Islam's fundamental sources—the Qur'an and the Sunna, —by placing them in their historical context, and then reinterpreting them, non-literally, in the light of the modern context."

Muhibb ud-Din al-Khateeb (1886–1969) was a Syrian Salafi writer. He was the maternal uncle of Ali al-Tantawi and was the author of the "hate filled" anti-Shia pamphlet entitled al-Khutoot al-‘Areedah. He has been described as "one of the most influential anti-Shiite polemicists of the twentieth century."

Ahmadiyya, officially the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community or the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama'at (AMJ) is an Islamic revival or messianic movement originating in British India in the late 19th century. It was founded by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1835–1908), who claimed to have been divinely appointed as both the Promised Mahdi and Messiah expected by Muslims to appear towards the end times and bring about, by peaceful means, the final triumph of Islam; as well as to embody, in this capacity, the expected eschatological figure of other major religious traditions. Adherents of the Ahmadiyya—a term adopted expressly in reference to Muhammad's alternative name Aḥmad—are known as Ahmadi Muslims or simply Ahmadis.

The Review of Religions is an English-language comparative religious magazine published monthly by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. Regularly in print since 1902, it is one of the longest running Islamic periodicals in English. It has been described as the main publication of the Ahmadiyya movement in the language and as a valuable source material for information on the geographical expansion of Ahmadi activity. The magazine was launched by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad with the aim of conveying an accurate understanding of Islamic teachings across the English-speaking world and dispelling misconceptions held against the faith. The articles, however, typically comprise distinctly Ahmadi perspectives. In addition to the English edition published from London, the magazine currently publishes separate quarterly editions in German, French and Spanish.

Ahmadiyya is an Islamic branch in Indonesia. The earliest history of the community in Indonesia dates back to the early days of the Second Caliph, when during the summer of 1925, roughly two decades prior to the Indonesian revolution, a missionary of the Community, Rahmat Ali, stepped on Indonesia's largest island, Sumatra, and established the movement with 13 devotees in Tapaktuan, in the province of Aceh. The Community has an influential history in Indonesia's religious development, yet in the modern times it has faced increasing intolerance from religious establishments in the country and physical hostilities from radical Muslim groups. The Association of Religion Data Archives estimates around 400,000 Ahmadi Muslims, spread over 542 branches across the country.

The Ahmadiyya branch in Islam has relationships with a number of other religions. Ahmadiyya consider themselves to be Muslim, but are not regarded as Muslim by mainstream Islam. Mainstream Muslim branches refer to the Ahmadiyya branch by the religious slur Qadiani, and to their beliefs as Qadianism a name based on Qadian, the small town in India's Punjab region where the founder of Ahmadiyya, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad was born.

Ahmadiyya is a persecuted branch of Islam in Saudi Arabia. Although there are many foreign workers and Saudi citizens belonging to the Ahmadiyya movement in Saudi Arabia, Ahmadis are officially banned from entering the country and from performing the pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina. This has led to criticisms from multiple human rights organizations.

Ahmadiyya is an Islamic branch in the United States. The earliest contact between the American people and the Ahmadiyya movement in Islam was during the lifetime of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad. In 1911, during the era of the First Caliphate of the Community, the Ahmadiyya movement in India began to prepare for its mission to the United States. However, it was not until 1920, during the era of the Second Caliphate, that Mufti Muhammad Sadiq, under the directive of the caliph, would leave England on SS Haverford for the United States. Sadiq established the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in the United States in 1920. The U.S. Ahmadiyya movement is considered by some historians as one of the precursors to the Civil Rights Movement in America. The Community was the most influential Muslim community in African-American Islam until the 1950s. Today, there are approximately 15,000 to 20,000 American Ahmadi Muslims spread across the country.

Ahmadiyya is an Islamic religious movement in Syria under the spiritual leadership of the caliph in London.

Al Fath was a weekly political magazine which existed between 1926 and 1948 in Cairo, Egypt. The magazine is known for its cofounder and editor Muhib Al Din Al Khatib and for its role in introducing Hasan Al Banna, founder of the Muslim Brotherhood, to the Egyptian political life. It called itself as the mirror of the Islamic world.