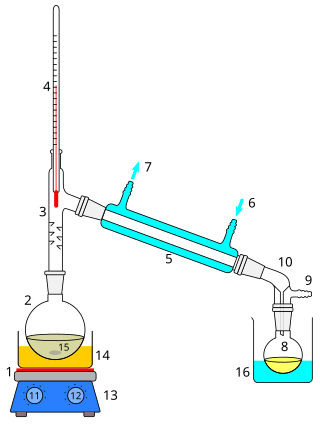

Cryogenic distillation process

Pure gases can be separated from air by first cooling it until it liquefies, then selectively distilling the components at their various boiling temperatures. The process can produce high purity gases but is energy-intensive. This process was pioneered by Carl von Linde in the early 20th century and is still used today to produce high purity gases. He developed it in the year 1895; the process remained purely academic for seven years before it was used in industrial applications for the first time (1902). [3]

The cryogenic separation process [4] [5] [6] requires a very tight integration of heat exchangers and separation columns to obtain a good efficiency and all the energy for refrigeration is provided by the compression of the air at the inlet of the unit.

To achieve the low distillation temperatures, an air separation unit requires a refrigeration cycle that operates by means of the Joule–Thomson effect, and the cold equipment has to be kept within an insulated enclosure (commonly called a "cold box"). The cooling of the gases requires a large amount of energy to make this refrigeration cycle work and is delivered by an air compressor. Modern ASUs use expansion turbines for cooling; the output of the expander helps drive the air compressor, for improved efficiency. The process consists of the following main steps: [7]

- Before compression the air is pre-filtered of dust.

- Air is compressed where the final delivery pressure is determined by recoveries and the fluid state (gas or liquid) of the products. Typical pressures range between 5 and 10 bar gauge. The air stream may also be compressed to different pressures to enhance the efficiency of the ASU. During compression water is condensed out in inter-stage coolers.

- The process air is generally passed through a molecular sieve bed, which removes any remaining water vapour, as well as carbon dioxide, which would freeze and plug the cryogenic equipment. Molecular sieves are often designed to remove any gaseous hydrocarbons from the air, since these can be a problem in the subsequent air distillation that could lead to explosions. [8] The molecular sieves bed must be regenerated. This is done by installing multiple units operating in alternating mode and using the dry co-produced waste gas to desorb the water.

- Process air is passed through an integrated heat exchanger (usually a plate fin heat exchanger) and cooled against product (and waste) cryogenic streams. Part of the air liquefies to form a liquid that is enriched in oxygen. The remaining gas is richer in nitrogen and is distilled to almost pure nitrogen (typically < 1ppm) in a high pressure (HP) distillation column. The condenser of this column requires refrigeration which is obtained from expanding the more oxygen rich stream further across a valve or through an expander (a reverse compressor).

- Alternatively the condenser may be cooled by interchanging heat with a reboiler in a low pressure (LP) distillation column (operating at 1.2-1.3 bar abs.) when the ASU is producing pure oxygen. To minimize the compression cost the combined condenser/reboiler of the HP/LP columns must operate with a temperature difference of only 1-2 K, requiring plate fin brazed aluminium heat exchangers. Typical oxygen purities range in from 97.5% to 99.5% and influences the maximum recovery of oxygen. The refrigeration required for producing liquid products is obtained using the Joule–Thomson effect in an expander which feeds compressed air directly to the low pressure column. Hence, a certain part of the air is not to be separated and must leave the low pressure column as a waste stream from its upper section.

- Because the boiling point of argon (87.3 K at standard conditions) lies between that of oxygen (90.2 K) and nitrogen (77.4 K), argon builds up in the lower section of the low pressure column. When argon is produced, a vapor side draw is taken from the low pressure column where the argon concentration is highest. It is sent to another column rectifying the argon to the desired purity from which liquid is returned to the same location in the LP column. Use of modern structured packings which have very low pressure drops enable argon with less than 1 ppm impurities. Though argon is present in less to 1% of the incoming, the air argon column requires a significant amount of energy due to the high reflux ratio required (about 30) in the argon column. Cooling of the argon column can be supplied from cold expanded rich liquid or by liquid nitrogen.

- Finally the products produced in gas form are warmed against the incoming air to ambient temperatures. This requires a carefully crafted heat integration that must allow for robustness against disturbances (due to switch over of the molecular sieve beds). [9] It may also require additional external refrigeration during start-up.

The separated products are sometimes supplied by pipeline to large industrial users near the production plant. Long distance transportation of products is by shipping liquid product for large quantities or as dewar flasks or gas cylinders for small quantities.