Cape Canaveral is a cape in Brevard County, Florida, in the United States, near the center of the state's Atlantic coast. Officially Cape Kennedy from 1963 to 1973, it lies east of Merritt Island, separated from it by the Banana River. It is part of a region known as the Space Coast, and is the site of the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. Since many U.S. spacecraft have been launched from both the station and the Kennedy Space Center on adjacent Merritt Island, the two are sometimes conflated with each other.

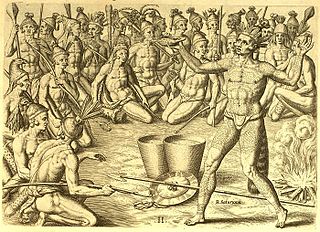

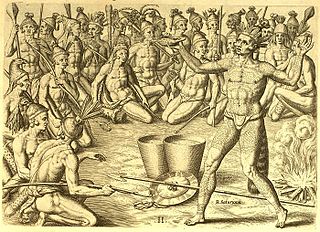

The Calusa were a Native American people of Florida's southwest coast. Calusa society developed from that of archaic peoples of the Everglades region. Previous indigenous cultures had lived in the area for thousands of years.

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés was a Spanish admiral, explorer and conquistador from Avilés, in Asturias, Spain. He is notable for planning the first regular trans-oceanic convoys, which became known as the Spanish treasure fleet, and for founding St. Augustine, Florida, in 1565. This was the first successful European settlement in La Florida and the most significant city in the region for nearly three centuries.

Tocobaga was the name of a chiefdom, its chief, and its principal town during the 16th century. The chiefdom was centered around the northern end of Old Tampa Bay, the arm of Tampa Bay that extends between the present-day city of Tampa and northern Pinellas County. The exact location of the principal town is believed to be the archeological Safety Harbor site, which gives its name to the Safety Harbor culture, of which the Tocobaga are the most well-known group.

Spanish Florida was the first major European land claim and attempted settlement in North America during the European Age of Discovery. La Florida formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and the Spanish Empire during Spanish colonization of the Americas. While its boundaries were never clearly or formally defined, the territory was initially much larger than the present-day state of Florida, extending over much of what is now the southeastern United States, including all of present-day Florida plus portions of Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, and the Florida Parishes of Louisiana. Spain's claim to this vast area was based on several wide-ranging expeditions mounted during the 16th century. A number of missions, settlements, and small forts existed in the 16th and to a lesser extent in the 17th century; they were eventually abandoned due to pressure from the expanding English and French colonial settlements, the collapse of the native populations, and the general difficulty in becoming agriculturally or economically self-sufficient. By the 18th century, Spain's control over La Florida did not extend much beyond a handful of forts near St. Augustine, St. Marks, and Pensacola, all within the boundaries of present-day Florida.

Jonathan Dickinson (1663–1722) was a merchant from Port Royal, Jamaica who was shipwrecked on the southeast coast of Florida in 1696, along with his family and the other passengers and crew members of the ship. He wrote about their experiences. The party was held captive by Jobe ("Hoe-bay") Indians for several days, and then was allowed to travel by small boat and on foot the 230 miles up the coast to Saint Augustine. The party was subjected to harassment and physical abuse at almost every step of the journey to Saint Augustine. Five members of the party died from exposure and starvation on the way.

The Jaega were Native Americans living in a chiefdom of the same name, which included the coastal parts of present-day Martin County and northern Palm Beach County, Florida at the time of initial European contact, and until the 18th century. The name Jobé, or Jové, has been identified as a synonym of Jaega, a sub-group of the Jaega, or a town of the Jaega.

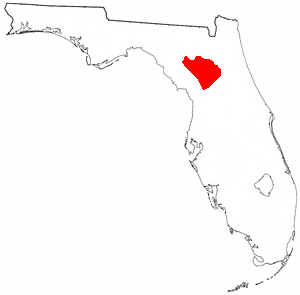

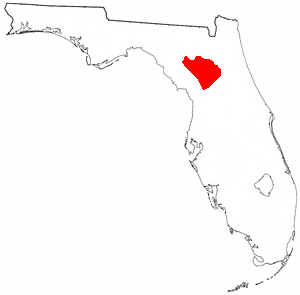

The Potano tribe lived in north-central Florida at the time of first European contact. Their territory included what is now Alachua County, the northern half of Marion County and the western part of Putnam County. This territory corresponds to that of the Alachua culture, which lasted from about 700 until 1700. The Potano were among the many tribes of the Timucua people, and spoke a dialect of the Timucua language.

The Mocama were a Native American people who lived in the coastal areas of what are now northern Florida and southeastern Georgia. A Timucua group, they spoke the dialect known as Mocama, the best-attested dialect of the Timucua language. Their heartland extended from about the Altamaha River in Georgia to south of the mouth of the St. John's River, covering the Sea Islands and the inland waterways, Intracoastal. and much of present-day Jacksonville. At the time of contact with Europeans, there were two major chiefdoms among the Mocama, the Saturiwa and the Tacatacuru, each of which evidently had authority over multiple villages. The Saturiwa controlled chiefdoms stretching to modern day St. Augustine, but the native peoples of these chiefdoms have been identified by Pareja as speaking Agua Salada, which may have been a distinct dialect.

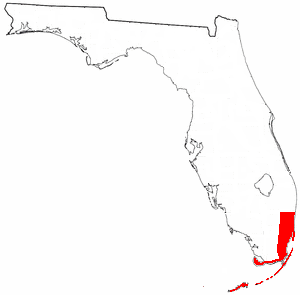

The Tequesta, also Tekesta, Tegesta, Chequesta, Vizcaynos, were a Native American tribe. At the time of first European contact they occupied an area along the southeastern Atlantic coast of Florida. They had infrequent contact with Europeans and had largely migrated by the middle of the 18th century.

The Surruque people lived along the middle Atlantic coast of Florida during the 16th and 17th centuries. They may have spoken a dialect of the Timucua language, but were allied with the Ais. The Surruque became clients of the Spanish government in St. Augustine, but were not successfully brought into the Spanish mission system.

Acuera was the name of both an indigenous town and a province or region in central Florida during the 16th and 17th centuries. The indigenous people of Acuera spoke a dialect of the Timucua language. In 1539 the town first encountered Europeans when it was raided by soldiers of Hernando de Soto's expedition. French colonists also knew this town during their brief tenure (1564–1565) in northern Florida.

The indigenous people of the Everglades region arrived in the Florida peninsula of what is now the United States approximately 14,000 to 15,000 years ago, probably following large game. The Paleo-Indians found an arid landscape that supported plants and animals adapted to prairie and xeric scrub conditions. Large animals became extinct in Florida around 11,000 years ago. Climate changes 6,500 years ago brought a wetter landscape. The Paleo-Indians slowly adapted to the new conditions. Archaeologists call the cultures that resulted from the adaptations Archaic peoples. They were better suited for environmental changes than their ancestors, and created many tools with the resources they had. Approximately 5,000 years ago, the climate shifted again to cause the regular flooding from Lake Okeechobee that gave rise to the Everglades ecosystems.

The Timucua were a Native American people who lived in Northeast and North Central Florida and southeast Georgia. They were the largest indigenous group in that area and consisted of about 35 chiefdoms, many leading thousands of people. The various groups of Timucua spoke several dialects of the Timucua language. At the time of European contact, Timucuan speakers occupied about 19,200 square miles (50,000 km2) in the present-day states of Florida and Georgia, with an estimated population of 200,000. Milanich notes that the population density calculated from those figures, 10.4 per square mile (4.0/km2) is close to the population densities calculated by other authors for the Bahamas and for Hispaniola at the time of first European contact. The territory occupied by Timucua speakers stretched from the Altamaha River and Cumberland Island in present-day Georgia as far south as Lake George in central Florida, and from the Atlantic Ocean west to the Aucilla River in the Florida Panhandle, though it reached the Gulf of Mexico at no more than a couple of points.

The indigenous peoples of Florida lived in what is now known as Florida for more than 12,000 years before the time of first contact with Europeans. However, the indigenous Floridians living east of the Apalachicola River had largely died out by the early 18th century. Some Apalachees migrated to Louisiana, where their descendants now live; some were taken to Cuba and Mexico by the Spanish in the 18th century, and a few may have been absorbed into the Seminole and Miccosukee tribes.

The Saturiwa were a Timucua chiefdom centered on the mouth of the St. Johns River in what is now Jacksonville, Florida. They were the largest and best attested chiefdom of the Timucua subgroup known as the Mocama, who spoke the Mocama dialect of Timucuan and lived in the coastal areas of present-day northern Florida and southeastern Georgia. They were a prominent political force in the early days of European settlement in Florida, forging friendly relations with the French Huguenot settlers at Fort Caroline in 1564 and later becoming heavily involved in the Spanish mission system.

The Agua Dulce or Agua Fresca (Freshwater) were a Timucua people of northeastern Florida. They lived in the St. Johns River watershed north of Lake George, and spoke a dialect of the Timucua language also known as Agua Dulce.

Tacatacuru was a Timucua chiefdom located on Cumberland Island in what is now the U.S. state of Georgia in the 16th and 17th centuries. It was one of two chiefdoms of the Timucua subgroup known as the Mocama, who spoke the Mocama dialect of Timucuan and lived in the coastal areas of southeastern Georgia and northern Florida.

Alvaro Mexia was a 17th-century Spanish explorer and cartographer of the east coast of Florida. Mexia was stationed in St Augustine and was given a diplomatic mission to the native populations living south of St. Augustine and in the Cape Canaveral area. This mission resulted in a "Period of Friendship" between the Spanish and the Ais native population.

San Buenaventura de Potano was a Spanish mission near Orange Lake in southern Alachua County or northern Marion County, Florida, located on the site where the town of Potano had been located when it was visited by Hernando de Soto in 1539. The Richardson/UF Village Site (8AL100), in southern Alachua County, has been proposed as the location of the town and mission.