Dyula is a language of the Mande language family spoken mainly in Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast and Mali, and also in some other countries, including Ghana, Guinea and Guinea-Bissau. It is one of the Manding languages and is most closely related to Bambara, being mutually intelligible with Bambara as well as Malinke. It is a trade language in West Africa and is spoken by millions of people, either as a first or second language. Similar to the other Mande languages, it uses tones. It may be written in the Latin, Arabic or N'Ko scripts.

Mansa Musa was the ninth Mansa of the Mali Empire, which reached its territorial peak during his reign. Musa's reign is often regarded as the zenith of Mali's power and prestige.

The following list consists of notable concepts that are derived from Islamic and associated cultural traditions, which are expressed as words in Arabic or Persian language. The main purpose of this list is to disambiguate multiple spellings, to make note of spellings no longer in use for these concepts, to define the concept in one or two lines, to make it easy for one to find and pin down specific concepts, and to provide a guide to unique concepts of Islam all in one place.

The Mali Empire was an empire in West Africa from c. 1226 to 1670. The empire was founded by Sundiata Keita and became renowned for the wealth of its rulers, especially Mansa Musa. At its peak, Mali was the largest empire in West Africa, widely influencing the culture of the region through the spread of its language, laws, and customs.

Osei Bonsu also known as Osei Tutu Kwame was the Asantehene. He reigned either from 1800 to 1824 or from 1804 to 1824. During his reign as the king, the Ashanti fought the Fante confederation and ended up dominating Gold Coast trade. In Akan, Bonsu means whale, and is symbolic of his achievement of extending the Ashanti Empire to the coast. He died in Kumasi, and was succeeded by Osei Yaw Akoto.

The Dyula are a Mande ethnic group inhabiting several West African countries, including Mali, Cote d'Ivoire, Ghana, and Burkina Faso.

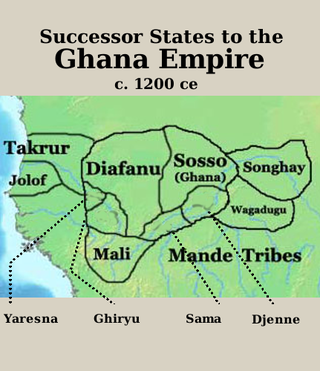

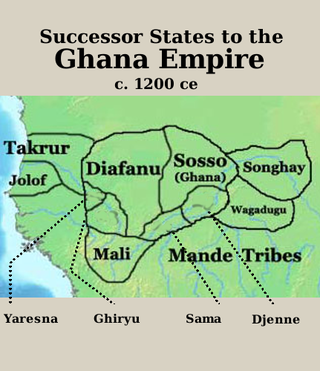

The Soninke people are a West African Mande-speaking ethnic group found in Mali, southern Mauritania, eastern Senegal, The Gambia, and Guinea. They speak the Soninke language, also called the Serakhulle or Azer language, which is one of the Mande languages. Soninke people were the founders of the ancient empire of Ghana or Wagadou c. 200–1240 CE, Subgroups of Soninke include the Jakhanke, Maraka and Wangara. When the Ghana empire was destroyed, the resulting diaspora brought Soninkes to Mali, Mauritania, Senegal, Gambia, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Guinée-Conakry, modern-day Republic of Ghana, Kano in Nigeria, and Guinea-Bissau where some of this trading diaspora was called Wangara.

Mansa Uli, also known as Yérélinkon, was the second mansa of the Mali Empire. He was the son and successor of Sunjata.

Sakura was a mansa of the Mali Empire who reigned during the late 13th century, known primarily from an account given by Ibn Khaldun in his Kitāb al-ʻIbar. Sakura was not a member of the ruling Keita dynasty, and may have been formerly enslaved. He usurped the throne following a period of political instability and led Mali to considerable territorial expansion. During his reign, trade between the Mali Empire and the rest of the Muslim world increased. He was killed in the early 1300s while returning from the hajj and the Keita dynasty was restored to power.

Essouk is a commune and small village in the Kidal Region of Mali. The village lies 45 km northwest of Kidal in the Adrar des Ifoghas massif. The ruins of the medieval town of Tadmakka lie 2 km northeast of the present village. Between the 9th and the 15th centuries Tadmekka served as an important entrepôt for the trans-Saharan trade.

The Karamogo were the scholar class among the peaceful Dyula traders of Western Africa, of which Al-Hajj Salim Suwari was a prominent member. The Karamogo developed theological rationales for living among non-Muslims, arguing that one should nurture one's own faith and let conversion happen in its own time. Accordingly, jihad should not be waged except in defensive contexts.

The Wangara are a subgroup of the Soninke who later became assimilated merchant classes that specialized in both Trans Saharan and Secret Trade of Gold Dust. Their diaspora operated all throughout West Africa Sahel-Sudan. Fostering regionally organized trade networks and Architecture projects. But based in the many Sahelian and Niger-Volta-Sene-Gambia river city-states. Particularly Dia, Timbuktu, Agadez, Kano, Gao, Koumbi Saleh, Guidimaka, Salaga, Kong, Bussa, Bissa, Kankan, Jallon, Djenné as well as Bambouk, Bure, Lobi, and Bono State goldfields and Borgu. They also were practicing Muslims with a clerical social class (Karamogo), Timbuktu Alumni political advisors, Sufi Mystic healers and individual leaders (Marabout). Living by a philosophy of mercantile pacifism called the Suwarian Tradition. Teaching peaceful coexistence with non-Muslims, reserving Jihad for self-defence only and even serving as Soothsayers or a "priesthood" of literate messengers for non-Muslim Chiefdoms/Kingdoms. This gave them a degree of control and immense wealth in lands where they were the minority. Creating contacts with almost all West African religious denominations. A group of Mande traders, loosely associated with the Kingdoms of the Sahel region and other West African Empires. Such as Ghana, Mali, Songhai, Bono State, Kong, Borgu, Dendi, Macina, Hausa Kingdoms & the Pashalik of Timbuktu. Wangara also describes any land south of Timbuktu and Agadez. The Bilad-Al-Sudan or Bilad-Al-Tibr, "Land of Black" or "Gold."

Islam in Africa is the continent's second most widely professed faith behind Christianity. Africa was the first continent into which Islam spread from Southwest Asia, during the early 7th century CE. Almost one-third of the world's Muslim population resides in Africa. Muslims crossed current Djibouti and Somalia to seek refuge in present-day Eritrea and Ethiopia during the Hijrah ("Migration") to the Christian Kingdom of Aksum. Like the vast majority (90%) of Muslims in the world, most Muslims in Africa are also Sunni Muslims; the complexity of Islam in Africa is revealed in the various schools of thought, traditions, and voices in many African countries. Many African ethnicities, mostly in North, West and East Africa consider Islam their Traditional religion. The practice of Islam on the continent is not static and is constantly being reshaped by prevalent social, economic, and political conditions. Generally Islam in Africa often adapted to African cultural contexts and belief systems forming Africa's own orthodoxies.

Pre-imperial Mali refers to the period of history before the establishment of the Mali Empire, an African empire located mostly in present-day Mali, in c. 1235.

Professor Emeritus Ivor G. Wilks was a noted British Africanist and historian, specializing in Ghana. Considered one of the founders of modern African historiography, he was an authority on the Ashanti Empire in Ghana and the Welsh working-class movement in the 19th century. At the time of his death, he was Professor Emeritus of History at Northwestern University in Illinois, USA.

The Marka people are a Mande people of northwest Mali. They speak Marka, a Manding language. Some of the Maraka (Dafin people are found in Ghana.

The Jakhanke -- also spelled Jahanka, Jahanke, Jahanque, Jahonque, Diakkanke, Diakhanga, Diakhango, Dyakanke, Diakhanké, Diakanké, or Diakhankesare -- are a Manding-speaking ethnic group in the Senegambia region, often classified as a subgroup of the larger Soninke. The Jakhanke have historically constituted a specialized caste of professional Muslim clerics (ulema) and educators. They are centered on one larger group in Guinea, with smaller populations in the eastern region of The Gambia, Senegal, and in Mali near the Guinean border. Although generally considered a branch of the Soninke, their language is closer to Western Manding languages such as Mandinka.

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community is the second largest group of Islam in Ghana after Sunni Islam. The early rise of the Community in Ghana can be traced through a sequence of events beginning roughly at the same time as the birth of the Ahmadiyya movement in 1889 in British India. It was during the early period of the Second Caliphate that the first missionary, Abdul Rahim Nayyar was sent to what was then the Gold Coast in 1921 upon invitation from Sunni Muslims in Saltpond. Having established the movement in the country, Nayyar left and was replaced by the first permanent missionary, Al Hajj Fadl-ul-Rahman Hakim in 1922.

Al-Hajj Abdul Rahim Nayyar was a companion of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad and a missionary of the Ahmadiyya Islamic movement in West Africa. He pledged allegiance to Ghulam Ahmad, formally joining the Ahmadiyya movement, in 1901. Travelling to the Gold Coast in 1921 upon invitation from Muslims in Saltpond, Nayyar was instrumental in consolidating Ahmadiyya missions in several West African countries.

Nehemia Levtzion was an Israeli scholar of African history, Near East, Islamic, and African studies, and the President of the Open University of Israel from 1987 to 1992 and the Executive Director of the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute from 1994 to 1997.