The history of the Soviet Union from 1982 through 1991 spans the period from the Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev's death until the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Due to the years of Soviet military buildup at the expense of domestic development, and complex systemic problems in the command economy, Soviet output stagnated. Failed attempts at reform, a standstill economy, and the success of the proxies of the United States against the Soviet Union's forces in the war in Afghanistan led to a general feeling of discontent, especially in the Soviet-occupied Baltic countries and Eastern Europe.

Konstantin Ustinovich Chernenko was a Soviet politician and the seventh General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. He briefly led the Soviet Union from 1984 until his death a year later.

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev was a Soviet and Russian politician and statesman who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to the country's dissolution in 1991. He served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1985 and additionally as head of state beginning in 1988, as Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet from 1988 to 1989, Chairman of the Supreme Soviet from 1989 to 1990 and the president of the Soviet Union from 1990 to 1991. Ideologically, Gorbachev initially adhered to Marxism–Leninism but moved towards social democracy by the early 1990s. He was the only Soviet leader born after the country's foundation.

Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov was a Soviet politician who was the sixth leader of the Soviet Union and the fourth General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, taking office in late 1982 and serving until his death in 1984.

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev was a Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until his death in 1982, and Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet from 1960 to 1964 and again from 1977 to 1982. His 18-year term as General Secretary was second only to Joseph Stalin's in duration.

The president of the Soviet Union, officially the president of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, abbreviated as president of the USSR, was the head of state of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics from 15 March 1990 to 25 December 1991.

Andrei Andreyevich Gromyko was a Soviet politician and diplomat during the Cold War. He served as Minister of Foreign Affairs (1957–1985) and as Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet (1985–1988). Gromyko was responsible for many top decisions on Soviet foreign policy until he retired in 1988. In the 1940s, Western pundits called him Mr Nyet, or Grim Grom, because of his frequent use of the Soviet veto in the United Nations Security Council.

Alexei Nikolayevich Kosygin was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as the Premier of the Soviet Union from 1964 to 1980 and was one of the most influential Soviet policymakers in the mid-1960s along with General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev.

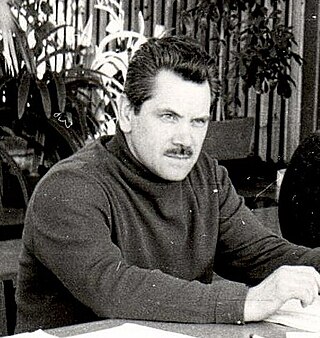

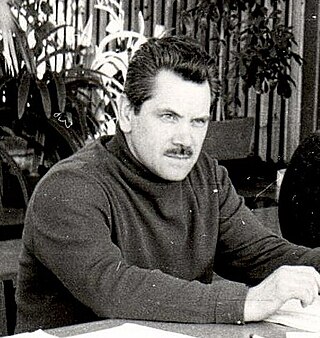

Alexander Nikolayevich Yakovlev was a Soviet and Russian politician, diplomat, and historian. A member of the Politburo and Secretariat of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union throughout the 1980s, he was termed the "godfather of glasnost", and was the intellectual force behind Mikhail Gorbachev's reform programme of glasnost and perestroika.

After the Russian Revolution, in which the Bolsheviks took over parts of the collapsing Russian Empire in 1918, they faced enormous odds against the German Empire and eventually negotiated terms to pull out of World War I. They then went to war against the White movement, pro-independence movements, rebellious peasants, former supporters, anarchists and foreign interventionists in the bitter civil war. They set up the Soviet Union in 1922 with Vladimir Lenin in charge. At first, it was treated as an unrecognized pariah state because of its repudiating of tsarist debts and threats to destroy capitalism at home and around the world. By 1922, Moscow had repudiated the goal of world revolution, and sought diplomatic recognition and friendly trade relations with the capitalist world, starting with Britain and Germany. Finally, in 1933, the United States gave recognition. Trade and technical help from Germany and the United States arrived in the late 1920s. After Lenin died in 1924, Joseph Stalin, became leader. He transformed the country in the 1930s into an industrial and military power. It strongly opposed Nazi Germany until August 1939, when it suddenly came to friendly terms with Berlin in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. Moscow and Berlin by agreement invaded and partitioned Poland and the Baltic States. Stalin ignored repeated warnings that Hitler planned to invade. He was caught by surprise in June 1941 when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. The Soviet forces nearly collapsed as the Germans reached the outskirts of Leningrad and Moscow. However, the Soviet Union proved strong enough to defeat Nazi Germany, with help from its key World War II allies, Britain and the United States. The Soviet army occupied most of Eastern Europe and increasingly controlled the governments.

The Cold War from 1979 to 1985, also called the Second Cold War, was a late phase of the Cold War marked by a sharp increase in hostility between the Soviet Union and the West. It arose from a strong denunciation of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979. With the election of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in 1979, and American President Ronald Reagan in 1980, a corresponding change in Western foreign policy approach toward the Soviet Union was marked by the rejection of détente in favor of the Reagan Doctrine policy of rollback, with the stated goal of dissolving Soviet influence in Soviet Bloc countries. During this time, the threat of nuclear war had reached new heights not seen since the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962.

Jack Foust Matlock Jr. is an American former ambassador, career Foreign Service Officer, teacher, historian, and linguist. He was a specialist in Soviet affairs during some of the most tumultuous years of the Cold War, and served as the U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union from 1987 to 1991.

Relations between the Soviet Union and the United States were fully established in 1933 as the succeeding bilateral ties to those between the Russian Empire and the United States, which lasted from 1776 until 1917; they were also the predecessor to the current bilateral ties between the Russian Federation and the United States that began in 1992 after the end of the Cold War. The relationship between the Soviet Union and the United States was largely defined by mistrust and tense hostility. The invasion of the Soviet Union by Germany as well as the attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor by Imperial Japan marked the Soviet and American entries into World War II on the side of the Allies in June and December 1941, respectively. As the Soviet–American alliance against the Axis came to an end following the Allied victory in 1945, the first signs of post-war mistrust and hostility began to immediately appear between the two countries, as the Soviet Union militarily occupied Eastern European countries and turned them into satellite states, forming the Eastern Bloc. These bilateral tensions escalated into the Cold War, a decades-long period of tense hostile relations with short phases of détente that ended after the collapse of the Soviet Union and emergence of the present-day Russian Federation at the end of 1991.

Canada and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics had diplomatic relations from 1923 to 1927 and from 1941 until the USSR's dissolution in 1991. The relationship was often tense, owing to the Cold War and Canada's membership in NATO.

Fyodor Davydovich Kulakov was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War.

Following the August 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt, the State Council of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) (‹See Tfd›Russian: Государственный Совет СССР), but also known as the State Soviet, was formed on 5 September 1991 and was designed to be one of the most important government offices in Mikhail Gorbachev's Soviet Union. The members of the council consisted of the President of the Soviet Union, and highest officials (which typically was presidents of their republics) from the Soviet Union's republics. During the period of transition it was the highest organ of state power, having the power to elect a prime minister, or a person who would take Gorbachev's place if absent; the office of Vice President of the Soviet Union had been abolished following the failed August Coup that very same year.

On 10 November 1982, Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, the third General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) and the fifth leader of the Soviet Union, died at the age of 75 after suffering heart failure following years of serious ailments. His death was officially acknowledged on 11 November simultaneously by Soviet radio and television. Brezhnev was given a state funeral after three full days of national mourning, then buried in an individual tomb on Red Square at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis. Yuri Andropov, Brezhnev's eventual successor as general secretary, was chairman of the committee in charge of managing Brezhnev's funeral, held on 15 November 1982, five days after his death.

The full understanding of the history of the late Soviet Union and of its successor, the Russian Federation, requires the assessment of the legacy of Leonid Brezhnev, the third General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) and twice Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet. Leonid Brezhnev was the leader of the CPSU from 1964 until his death in 1982, whose eighteen-year tenure has been recognized for developing the most powerful military, and for social and economic stagnation in the late Soviet Union.

Anatoly Sergeevich Chernyaev was a Russian politician and writer, member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the USSR, who became foreign-policy advisor to General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev in 1986-1991.