A loincloth is a one-piece garment, either wrapped around itself or kept in place by a belt. It covers the genitals and sometimes the buttocks. Loincloths which are held up by belts or strings are specifically known as breechcloth or breechclout. Often, the flaps hang down in front and back.

Filipinos are citizens or people identified with the country of the Philippines. The majority of Filipinos today come from various Austronesian peoples, all typically speaking Filipino, English, or other Philippine languages. Currently, there are more than 185 ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines each with its own language, identity, culture, tradition, and history.

The Boxer Codex is a late-16th-century Spanish manuscript produced in the Philippines. It contains 75 colored illustrations of the peoples of China, the Philippines, Java, the Moluccas, the Ladrones, and Siam. About 270 pages of Spanish text describe these places, their inhabitants and customs. An additional 88 smaller drawings show mythological deities and demons, and both real and mythological birds and animals copied from popular Chinese texts and books in circulation at the time.

The timawa were the feudal warrior class of the ancient Visayan societies of the Philippines. They were regarded as higher than the uripon but below the tumao in the Visayan social hierarchy. They were roughly similar to the Tagalog maharlika caste.

The Tagalog maginoo, the Kapampangan ginu, and the Visayan tumao were the nobility social class among various cultures of the pre-colonial Philippines. Among the Visayans, the tumao were further distinguished from the immediate royal families, the kadatuan.

The baro’t saya or baro at saya is a traditional dress ensemble worn by women in the Philippines. It is a national dress of the Philippines and combines elements from both the precolonial native Filipino and colonial Spanish clothing styles. It traditionally consists of four parts: a blouse, a long skirt, a kerchief worn over the shoulders, and a short rectangular cloth worn over the skirt.

Bahag is a loincloth that was commonly used by men throughout the pre-colonial Philippines. They were either made from barkcloth or from hand-woven textiles. Before the colonial period, bahag were a common garment for commoners and the serf class. Bahag survives in some indigenous tribes of the Philippines today - most notably the Cordillerans in Northern Luzon.

In early Philippine history, the Tagalog settlement at Tondo sometimes referred to as the Kingdom of Tondo, was a major trade hub located on the northern part of the Pasig River delta, on Luzon island. Together with Maynila, the polity (bayan) that was also situated on the southern part of the Pasig River delta, had established a shared monopoly on the trade of Chinese goods throughout the rest of the Philippine archipelago, making it an established force in trade throughout Southeast Asia and East Asia.

The cultural achievements of pre-colonial Philippines include those covered by the prehistory and the early history (900–1521) of the Philippine archipelago's inhabitants, the pre-colonial forebears of today's Filipino people. Among the cultural achievements of the native people's belief systems, and culture in general, that are notable in many ethnic societies, range from agriculture, societal and environmental concepts, spiritual beliefs, up to advances in technology, science, and the arts.

In Philippine history, the Tagalog bayan of Maynila was one of the most cosmopolitan of the early historic settlements on the Philippine archipelago. Fortified with a wooden palisade which was appropriate for the predominant battle tactics of its time, it lay on the southern part of the Pasig River delta, where the district of Intramuros in Manila currently stands, and across the river from the separately-led Tondo polity.

The known recorded history of the Philippines between 900 and 1565 begins with the creation of the Laguna Copperplate Inscription in 900 and ends with the beginning of Spanish colonization in 1565. The inscription records its date of creation in the year 822 of the Hindu Saka calendar, corresponding to 900 AD in the Gregorian calendar. Therefore, the recovery of this document marks the end of the prehistory of the Philippines at 900 AD. During this historical time period, the Philippine archipelago was home to numerous kingdoms and sultanates and was a part of the theorized Indosphere and Sinosphere.

In early Philippine history, barangay is the term historically used by scholars to describe the complex sociopolitical units that were the dominant organizational pattern among the various peoples of the Philippine archipelago in the period immediately before the arrival of European colonizers. Academics refer to these settlements using the technical term "polity", but they are usually simply called "barangays".

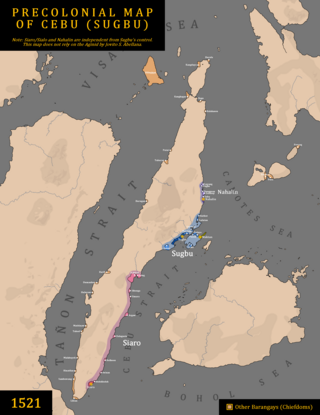

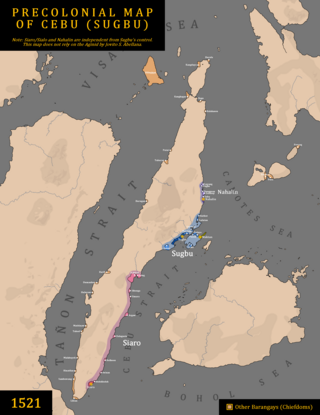

The Rajahnate of Cebu or Cebu also called as Sugbu, was an Indianized Raja monarchy Mandala (Polity) on the island of Cebu in the Philippines prior to the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors. It is known in ancient Chinese records as the nation of Sokbu (束務). According to Visayan oral legend, it was founded by Sri Lumay or Rajamuda Lumaya, a minor prince of the Tamil Chola dynasty. He was sent by the Chola Dynasty emperor from southern India to establish a base for expeditionary forces, but he rebelled and established his own independent polity. The capital of the nation was Singhapala (சிங்கப்பூர்) which is Tamil-Sanskrit for "Lion City", the same rootwords with the modern city-state of Singapore.

The maharlika were the feudal warrior class in ancient Tagalog society in Luzon, the Philippines. They belonged to the lower nobility class similar to the timawa of the Visayan people. In modern Filipino, however, the word has come to refer to aristocrats or to royal nobility, which was actually restricted to the hereditary maginoo class.

Malay is spoken by a minority of Filipinos, particularly in the Palawan, Sulu Archipelago and parts of Mindanao, mostly in the form of trade and creole languages, such as Sabah Malay.

The prehistory of Manila covers the Pleistocene epoch along with the Paleolithic, Neolithic, and Metal ages. It also includes the age of contact with other countries like China, and ends with the period of the Kingdom of Maynila.

Warfare in pre-colonial Philippines refers to the military history of the Philippines prior to Spanish colonization.

In the Philippine languages, a complex system of titles and honorifics was used extensively during the pre-colonial era, mostly by the Tagalogs and Visayans. These were borrowed from the Malay system of honorifics obtained from the Moro peoples of Mindanao, which in turn was based on the Indianized Sanskritized honorifics system in addition to the Chinese system of honorifics used in areas like Ma-i (Mindoro) and Pangasinan. The titles of historical figures such as Rajah Sulayman, Lakandula and Dayang Kalangitan evidence Indian influence. Malay titles are still used by the royal houses of Sulu, Maguindanao, Maranao and Iranun on the southern Philippine island of Mindanao. However, these are retained on a traditional basis as the 1987 Constitution explicitly reaffirms the abolition of royal and noble titles in the republic.

Karakoa were large outrigger warships from the Philippines. They were used by native Filipinos, notably the Kapampangans and the Visayans, during seasonal sea raids. Karakoa were distinct from other traditional Philippine sailing vessels in that they were equipped with platforms for transporting warriors and for fighting at sea. During peacetime, they were also used as trading ships. Large karakoa, which could carry hundreds of rowers and warriors, were known as joangas by the Spanish.