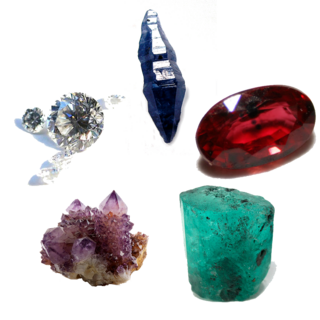

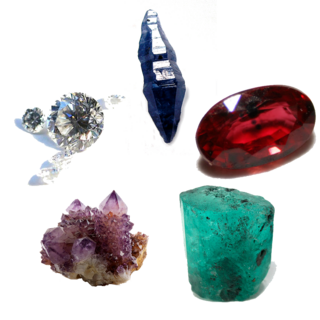

Emerald is a gemstone and a variety of the mineral beryl (Be3Al2(SiO3)6) colored green by trace amounts of chromium or sometimes vanadium. Beryl has a hardness of 7.5–8 on the Mohs scale. Most emeralds have lots of material trapped inside during the gem's formation, so their toughness (resistance to breakage) is classified as generally poor. Emerald is a cyclosilicate.

A gemstone is a piece of mineral crystal which, in cut and polished form, is used to make jewelry or other adornments. However, certain rocks and occasionally organic materials that are not minerals are also used for jewelry and are therefore often considered to be gemstones as well. Most gemstones are hard, but some soft minerals are used in jewelry because of their luster or other physical properties that have aesthetic value. Rarity and notoriety are other characteristics that lend value to gemstones.

Sapphire is a precious gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum, consisting of aluminium oxide (α-Al2O3) with trace amounts of elements such as iron, titanium, cobalt, lead, chromium, vanadium, magnesium, boron, and silicon. The name sapphire is derived via the Latin "sapphirus" from the Greek "sappheiros", which referred to lapis lazuli. It is typically blue, but natural "fancy" sapphires also occur in yellow, purple, orange, and green colors; "parti sapphires" show two or more colors. Red corundum stones also occur, but are called rubies rather than sapphires. Pink-colored corundum may be classified either as ruby or sapphire depending on locale. Commonly, natural sapphires are cut and polished into gemstones and worn in jewelry. They also may be created synthetically in laboratories for industrial or decorative purposes in large crystal boules. Because of the remarkable hardness of sapphires – 9 on the Mohs scale (the third hardest mineral, after diamond at 10 and moissanite at 9.5) – sapphires are also used in some non-ornamental applications, such as infrared optical components, high-durability windows, wristwatch crystals and movement bearings, and very thin electronic wafers, which are used as the insulating substrates of special-purpose solid-state electronics such as integrated circuits and GaN-based blue LEDs. Sapphire is the birthstone for September and the gem of the 45th anniversary. A sapphire jubilee occurs after 65 years.

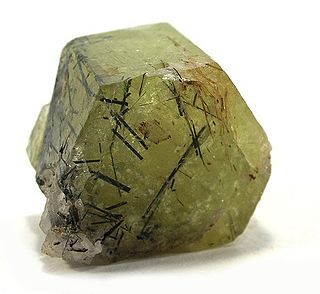

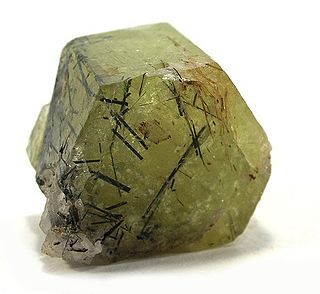

Topaz is a silicate mineral of aluminium and fluorine with the chemical formula Al2SiO4(F,OH)2. It is used as a gemstone in jewelry and other adornments. Common topaz in its natural state is colorless, though trace element impurities can make it pale blue or golden brown to yellow orange. Topaz is often treated with heat or radiation to make it a deep blue, reddish-orange, pale green, pink, or purple.

A ruby is a pinkish red to blood-red colored gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum. Ruby is one of the most popular traditional jewelry gems and is very durable. Other varieties of gem-quality corundum are called sapphires. Ruby is one of the traditional cardinal gems, alongside amethyst, sapphire, emerald, and diamond. The word ruby comes from ruber, Latin for red. The color of a ruby is due to the element chromium.

The mineral or gemstone chrysoberyl is an aluminate of beryllium with the formula BeAl2O4. The name chrysoberyl is derived from the Greek words χρυσός chrysos and βήρυλλος beryllos, meaning "a gold-white spar". Despite the similarity of their names, chrysoberyl and beryl are two completely different gemstones, although they both contain beryllium. Chrysoberyl is the third-hardest frequently encountered natural gemstone and lies at 8.5 on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness, between corundum (9) and topaz (8).

Lustre is the way light interacts with the surface of a crystal, rock, or mineral. The word traces its origins back to the Latin lux, meaning "light", and generally implies radiance, gloss, or brilliance.

The Star of India is a 563.35-carat star sapphire, one of the largest such gems in the world. It is almost flawless and is unusual in that it has stars on both sides of the stone. The greyish-blue gem was mined in Sri Lanka and is housed in the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

In mineralogy, an inclusion is any material that is trapped inside a mineral during its formation. In gemology, an inclusion is a characteristic enclosed within a gemstone, or reaching its surface from the interior.

An asterism is a star-shaped concentration of light reflected or refracted from a gemstone. It can appear when a suitable stone is cut en cabochon.

The Logan Sapphire is a 422.98-carat (84.596 g) sapphire from Sri Lanka. One of the largest blue faceted sapphires in the world, it was owned by Sir Victor Sassoon and then purchased by M. Robert Guggenheim as a gift for his wife, Rebecca Pollard Guggenheim, who donated the sapphire to the Smithsonian Institution in 1960. The sapphire's name is derived from Rebecca's new surname after she later married John A. Logan. It has been on display in the National Gem Collection of the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., since 1971. It is a mixed cushion-cut sapphire, approximately the size of a large chicken egg, and set in a silver and gold brooch surrounded by 20 round brilliant-cut diamonds.

The Eagle Diamond is a gemstone discovered in Eagle, Wisconsin in 1876 that was about 16 carats. It was found on a hillside about 30 feet below the surface in glacial till while digging a well. It was one of more than a dozen rare gems stolen in a heist from the American Museum of Natural History in 1964 and remains missing to this day.

The Star of Bombay is a 182-carat (36.4-g) cabochon-cut star sapphire originating in Sri Lanka. The violet-blue gem was given to silent film actress Mary Pickford by her husband, Douglas Fairbanks. She bequeathed it to the Smithsonian Institution. It is the namesake of the popular alcoholic beverage Bombay Sapphire, a British-manufactured gin.

Hiddenite, North Carolina, United States, is a centre for the mining of gemstones. Three larger mines found there are Adams Mine, NAEM and the Emerald Hollow Mine. They are collectively known as the Hiddenite Gem Mines.

Morganite is an orange or pink variety of beryl and is also a gemstone. Morganite is mined in Brazil, Afghanistan, Mozambique, Namibia, the United States, and Madagascar.

Aquamarine is a pale-blue to light-green variety of beryl. The color of aquamarine can be changed by heat.