The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution funded by 190 member countries, with headquarters in Washington, D.C. It is regarded as the global lender of last resort to national governments, and a leading supporter of exchange-rate stability. Its stated mission is "working to foster global monetary cooperation, secure financial stability, facilitate international trade, promote high employment and sustainable economic growth, and reduce poverty around the world." Established on December 27, 1945 at the Bretton Woods Conference, primarily according to the ideas of Harry Dexter White and John Maynard Keynes, it started with 29 member countries and the goal of reconstructing the international monetary system after World War II. It now plays a central role in the management of balance of payments difficulties and international financial crises. Through a quota system, countries contribute funds to a pool from which countries can borrow if they experience balance of payments problems. As of 2016, the fund had SDR 477 billion.

Following their defeat in World War I, the Central Powers agreed to pay war reparations to the Allied Powers. Each defeated power was required to make payments in either cash or kind. Because of the financial situation in Austria, Hungary, and Turkey after the war, few to no reparations were paid and the requirements for reparations were cancelled. Bulgaria, having paid only a fraction of what was required, saw its reparation figure reduced and then cancelled. Historians have recognized the German requirement to pay reparations as the "chief battleground of the post-war era" and "the focus of the power struggle between France and Germany over whether the Versailles Treaty was to be enforced or revised."

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the late 1920s to 1932 as well as from 1944 until 1971 when the United States unilaterally terminated convertibility of the US dollar to gold, effectively ending the Bretton Woods system. Many states nonetheless hold substantial gold reserves.

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes was an English economist and philosopher whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originally trained in mathematics, he built on and greatly refined earlier work on the causes of business cycles. One of the most influential economists of the 20th century, he produced writings that are the basis for the school of thought known as Keynesian economics, and its various offshoots. His ideas, reformulated as New Keynesianism, are fundamental to mainstream macroeconomics. He is known as the "father of macroeconomics".

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States, was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, France, Republic of China, and other Allied nations of the Second World War with food, oil, and materiel between 1941 and 1945. The aid was given free of charge on the basis that such help was essential for the defense of the United States.

A reserve currency is a foreign currency that is held in significant quantities by central banks or other monetary authorities as part of their foreign exchange reserves. The reserve currency can be used in international transactions, international investments and all aspects of the global economy. It is often considered a hard currency or safe-haven currency.

The Bretton Woods Conference, formally known as the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, was the gathering of 730 delegates from all 44 allied nations at the Mount Washington Hotel, in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, United States, to regulate the international monetary and financial order after the conclusion of World War II.

The Bretton Woods system of monetary management established the rules for commercial relations among the United States, Canada, Western European countries, and Australia among 44 other countries after the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement. The Bretton Woods system was the first example of a fully negotiated monetary order intended to govern monetary relations among independent states. The Bretton Woods system required countries to guarantee convertibility of their currencies into U.S. dollars to within 1% of fixed parity rates, with the dollar convertible to gold bullion for foreign governments and central banks at US$35 per troy ounce of fine gold. It also envisioned greater cooperation among countries in order to prevent future competitive devaluations, and thus established the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to monitor exchange rates and lend reserve currencies to nations with balance of payments deficits.

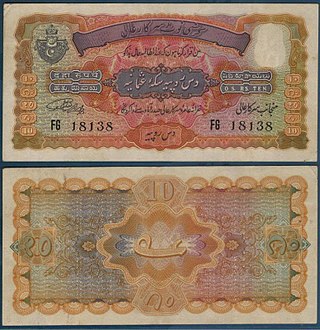

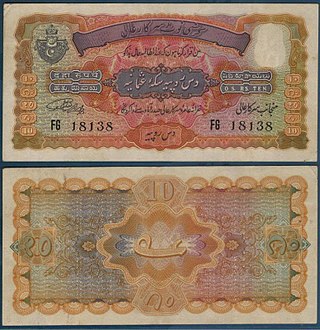

In public finance, a currency board is a monetary authority which is required to maintain a fixed exchange rate with a foreign currency. This policy objective requires the conventional objectives of a central bank to be subordinated to the exchange rate target. In colonial administration, currency boards were popular because of the advantages of printing appropriate denominations for local conditions, and it also benefited the colony with the seigniorage revenue. However, after World War II many independent countries preferred to have central banks and independent currencies.

In macroeconomics and modern monetary policy, a devaluation is an official lowering of the value of a country's currency within a fixed exchange-rate system, in which a monetary authority formally sets a lower exchange rate of the national currency in relation to a foreign reference currency or currency basket. The opposite of devaluation, a change in the exchange rate making the domestic currency more expensive, is called a revaluation. A monetary authority maintains a fixed value of its currency by being ready to buy or sell foreign currency with the domestic currency at a stated rate; a devaluation is an indication that the monetary authority will buy and sell foreign currency at a lower rate.

The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919) is a book written and published by the British economist John Maynard Keynes. After the First World War, Keynes attended the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 as a delegate of the British Treasury. At the conference as a representative of the British Treasury and deputy to the Chancellor of the Exchequer on the Supreme Economic Council he had publicly urged and secretly arranged on behalf of 'Rosie' Wemyss for a discontinuing of the food blockade of Germany but became ill and on his return found that there was 'no hope' of an economically sustainable settlement, and so resigned. In this book, he presents his arguments for a much less onerous treaty for a wider readership, not just for the sake of German civilians but for the sake of the economic well-being of all of Europe and beyond, including the Allied Powers, which the Treaty of Versailles and its associated treaties endangered.

Sir Henry Roy Forbes Harrod was an English economist. He is best known for writing The Life of John Maynard Keynes (1951) and for the development of the Harrod–Domar model, which he and Evsey Domar developed independently. He is also known for his International Economics, a former standard textbook, the first edition of which contained some observations and ruminations that would foreshadow theories developed independently by later scholars.

Robert Jacob Alexander, Baron Skidelsky, is a British economic historian. He is the author of a three-volume award-winning biography of British economist John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946). Skidelsky read history at Jesus College, Oxford, and is Emeritus Professor of Political Economy at the University of Warwick, England.

The Triffin dilemma or Triffin paradox is the conflict of economic interests that arises between short-term domestic and long-term international objectives for countries whose currencies serve as global reserve currencies. This dilemma was identified in the 1960s by Belgian-American economist Robert Triffin, who pointed out that the country whose currency, being the global reserve currency, foreign nations wish to hold, must be willing to supply the world with an extra supply of its currency to fulfill world demand for these foreign exchange reserves, leading to a trade deficit.

The sterling area was a group of countries that either pegged their currencies to sterling, or actually used sterling as their own currency.

Monetary hegemony is an economic and political concept in which a single state has decisive influence over the functions of the international monetary system. A monetary hegemon would need:

An international monetary system is a set of internationally agreed rules, conventions and supporting institutions that facilitate international trade, cross border investment and generally the reallocation of capital between states that have different currencies. It should provide means of payment acceptable to buyers and sellers of different nationalities, including deferred payment. To operate successfully, it needs to inspire confidence, to provide sufficient liquidity for fluctuating levels of trade, and to provide means by which global imbalances can be corrected. The system can grow organically as the collective result of numerous individual agreements between international economic factors spread over several decades. Alternatively, it can arise from a single architectural vision, as happened at Bretton Woods in 1944.

The Billion Dollar Gift and Mutual Aid were financial incentives instituted by the Canadian minister C. D. Howe during World War II.

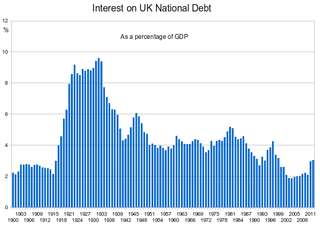

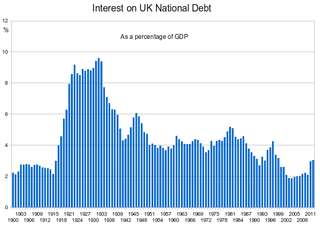

The history of the British national debt can be traced back to the reign of William III, who engaged a syndicate of City traders and merchants to offer for sale an issue of government debt, which evolved into the Bank of England. In 1815, at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, British government debt reached a peak of £1 billion.

The UK-US relations in World War II comprised an extensive and highly complex relationships, in terms of diplomacy, military action, financing, and supplies. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and American President Franklin D. Roosevelt formed close personal ties, that operated apart from their respective diplomatic and military organizations.