The Marshall Plan was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred $13.3 billion in economic recovery programs to Western European economies after the end of World War II. Replacing an earlier proposal for a Morgenthau Plan, it operated for four years beginning on April 3, 1948, though in 1951, the Marshall Plan was largely replaced by the Mutual Security Act. The goals of the United States were to rebuild war-torn regions, remove trade barriers, modernize industry, improve European prosperity and prevent the spread of communism. The Marshall Plan proposed the reduction of interstate barriers and the economic integration of the European Continent while also encouraging an increase in productivity as well as the adoption of modern business procedures.

Following their defeat in World War I, the Central Powers agreed to pay war reparations to the Allied Powers. Each defeated power was required to make payments in either cash or kind. Because of the financial situation in Austria, Hungary, and Turkey after the war, few to no reparations were paid and the requirements for reparations were cancelled. Bulgaria, having paid only a fraction of what was required, saw its reparation figure reduced and then cancelled. Historians have recognized the German requirement to pay reparations as the "chief battleground of the post-war era" and "the focus of the power struggle between France and Germany over whether the Versailles Treaty was to be enforced or revised."

The Rothschild family is a wealthy Ashkenazi Jewish noble banking family originally from Frankfurt that rose to prominence with Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744–1812), a court factor to the German Landgraves of Hesse-Kassel in the Free City of Frankfurt, Holy Roman Empire, who established his banking business in the 1760s. Unlike most previous court factors, Rothschild managed to bequeath his wealth and established an international banking family through his five sons, who established businesses in London, Paris, Frankfurt, Vienna, and Naples. The family was elevated to noble rank in the Holy Roman Empire and the United Kingdom. The family's documented history starts in 16th century Frankfurt; its name is derived from the family house, Rothschild, built by Isaak Elchanan Bacharach in Frankfurt in 1567.

The Treaty of Sèvres was a 1920 treaty signed between the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ceded large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, as well as creating large occupation zones within the Ottoman Empire. It was one of a series of treaties that the Central Powers signed with the Allied Powers after their defeat in World War I. Hostilities had already ended with the Armistice of Mudros.

The United States occupation of Haiti began on July 28, 1915, when 330 U.S. Marines landed at Port-au-Prince, Haiti, after the National City Bank of New York convinced the President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, to take control of Haiti's political and financial interests. The July 1915 invasion took place following years of socioeconomic instability within Haiti that culminated with the lynching of President of Haiti Vilbrun Guillaume Sam by a mob angered by his decision to order the executions of political prisoners. The invasion and subsequent occupation was promoted by growing American business interests in Haiti, especially the National City Bank of New York, which had withheld funds from Haiti and paid rebels to destabilize the nation through the Bank of the Republic of Haiti with an aim at inducing American intervention.

The Young Plan was a 1929 attempt to settle issues surrounding the World War I reparations obligations that Germany owed under the terms of Treaty of Versailles. Developed to replace the 1924 Dawes Plan, the Young Plan was negotiated in Paris from February to June 1929 by a committee of international financial experts under the leadership of American businessman and economist Owen D. Young. Representatives of the affected governments then finalised and approved the plan at The Hague conference of 1929/30. Reparations were set at 36 billion Reichsmarks payable through 1988. Including interest, the total came to 112 billion Reichsmarks. The average annual payment was approximately two billion Reichsmarks. The plan came into effect on 17 May 1930, retroactive to 1 September 1929.

Following the termination of hostilities in World War II, the Allies were in control of the defeated Axis countries. Anticipating the defeat of Germany and Japan, they had already set up the European Advisory Commission and a proposed Far Eastern Advisory Commission to make recommendations for the post-war period. Accordingly, they managed their control of the defeated countries through Allied Commissions, often referred to as Allied Control Commissions (ACC), consisting of representatives of the major Allies.

Sir Cecil Arthur Spring Rice, was a British diplomat who served as British Ambassador to the United States from 1912 to 1918, as which he was responsible for the organisation of British efforts to end American neutrality during the First World War.

John Pierpont Morgan Jr. was an American banker, finance executive, and philanthropist. He inherited the family fortune and took over the business interests including J.P. Morgan & Co. after his father J. P. Morgan died in 1913.

The Lausanne Conference of 1932, held from 16 June to 9 July 1932 in Lausanne, Switzerland, was a meeting of representatives from the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Belgium, Japan and Germany that resulted in an agreement to lower Germany's World War I reparations obligations as imposed by the Treaty of Versailles and the 1929 Young Plan. The reduction of approximately 90 per cent was made as a result of the difficult economic circumstances during the Great Depression. The Lausanne Treaty never came into effect because it was dependent on an agreement with the United States on the repayment of the loans it had made to the Allied powers during World War I, and that agreement was never reached. The Lausanne Conference marked the de facto end of Germany's reparations payments until after World War II.

The Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas, generally referred to from 1982 as Paribas, was a French investment bank based in Paris. In May 2000, it merged with the Banque Nationale de Paris to form BNP Paribas.

The London Agreement on German External Debts, also known as the London Debt Agreement, was a debt relief treaty between the Federal Republic of Germany and creditor nations. The Agreement was signed in London on 27 February 1953, and came into force on 16 September 1953.

Sir Edgar Speyer, 1st Baronet was an American-born financier and philanthropist. He became a British subject in 1892 and was chairman of Speyer Brothers, the British branch of the Speyer family's international finance house, and a partner in the German and American branches. He was chairman of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London from 1906 to 1915, a period during which the company opened three underground railway lines, electrified a fourth and took over two more.

The United States entered into World War I in April 1917, more than two and a half years after the war began in Europe.

The United States declared war on the German Empire on April 6, 1917, nearly three years after World War I started. A ceasefire and armistice were declared on November 11, 1918. Before entering the war, the U.S. had remained neutral, though it had been an important supplier to the United Kingdom, France, and the other powers of the Allies of World War I.

The economic history of World War I covers the methods used by the First World War (1914–1918), as well as related postwar issues such as war debts and reparations. It also covers the economic mobilization of labour, industry, and agriculture leading to economic failure. It deals with economic warfare such as the blockade of Germany, and with some issues closely related to the economy, such as military issues of transportation. For a broader perspective see Home front during World War I.

The diplomatic history of World War I covers the non-military interactions among the major players during World War I. For the domestic histories of participants see home front during World War I. For a longer-term perspective see international relations (1814–1919) and causes of World War I. For the following (post-war) era see international relations (1919–1939). The major "Allies" grouping included Great Britain and its empire, France, Russia, Italy and the United States. Opposing the Allies, the major Central Powers included Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire (Turkey) and Bulgaria. Other countries also joined the Allies. For a detailed chronology see timeline of World War I.

The Balfour Mission, also referred to as the Balfour Visit, was a formal diplomatic visit to the United States by the British Government during World War I, shortly after the United States declaration of war on Germany (1917).

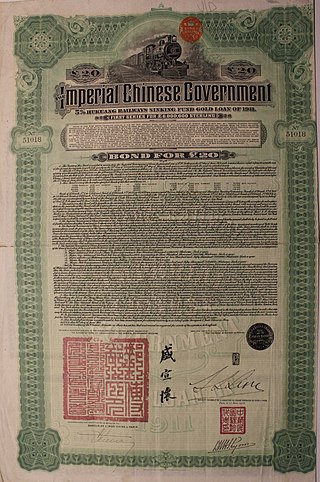

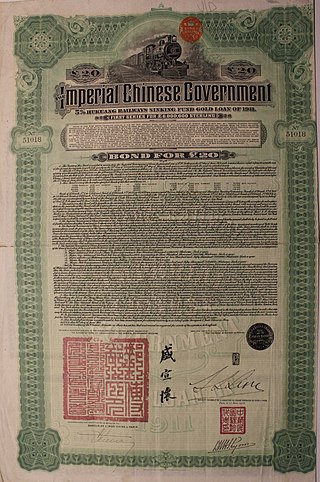

The China Consortium, also referred to as banking consortium or financial consortium or four-, five-, or six-power consortium depending on context, refers to two successive cooperative arrangements formed by foreign banks under their respective governments' directions in the early 20th century, to coordinate lending to the Chinese government. These initiatives were resented by Chinese nationalists and later similarly criticized by Chinese Communists, as instruments of colonialism wielded by Western nations and Japan.

The Economic and Financial Organization was the largest of the technical arms of the League of Nations, and the world's first international organization dedicated to promoting economic and monetary co-operation. It took shape in the early 1920s and was in activity until the creation of the United Nations in 1945. It has been described as having had seminal influence on postwar economic institutions, notably the International Monetary Fund (IMF).