In linguistics, syntax is the study of how words and morphemes combine to form larger units such as phrases and sentences. Central concerns of syntax include word order, grammatical relations, hierarchical sentence structure (constituency), agreement, the nature of crosslinguistic variation, and the relationship between form and meaning (semantics). There are numerous approaches to syntax that differ in their central assumptions and goals.

In general linguistics, the comparative is a syntactic construction that serves to express a comparison between two entities or groups of entities in quality or degree - see also comparison (grammar) for an overview of comparison, as well as positive and superlative degrees of comparison.

In linguistics, a verb phrase (VP) is a syntactic unit composed of a verb and its arguments except the subject of an independent clause or coordinate clause. Thus, in the sentence A fat man quickly put the money into the box, the words quickly put the money into the box constitute a verb phrase; it consists of the verb put and its arguments, but not the subject a fat man. A verb phrase is similar to what is considered a predicate in traditional grammars.

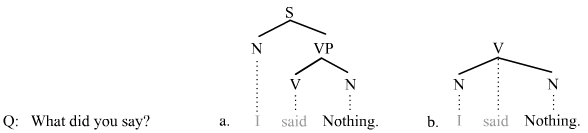

In syntactic analysis, a constituent is a word or a group of words that function as a single unit within a hierarchical structure. The constituent structure of sentences is identified using tests for constituents. These tests apply to a portion of a sentence, and the results provide evidence about the constituent structure of the sentence. Many constituents are phrases. A phrase is a sequence of one or more words built around a head lexical item and working as a unit within a sentence. A word sequence is shown to be a phrase/constituent if it exhibits one or more of the behaviors discussed below. The analysis of constituent structure is associated mainly with phrase structure grammars, although dependency grammars also allow sentence structure to be broken down into constituent parts.

Historically, grammarians have described preposition stranding or p-stranding as the syntactic construction in which a so-called stranded, hanging or dangling preposition occurs somewhere other than immediately before its corresponding object; for example, at the end of a sentence. The term preposition stranding was coined in 1964, predated by stranded preposition in 1949. Linguists had previously identified such a construction as a sentence-terminal preposition or as a preposition at the end. This kind of construction is found in English, and more generally in other Germanic languages.

In syntax, sluicing is a type of ellipsis that occurs in both direct and indirect interrogative clauses. The ellipsis is introduced by a wh-expression, whereby in most cases, everything except the wh-expression is elided from the clause. Sluicing has been studied in detail in the early 21st century and it is therefore a relatively well-understood type of ellipsis. Sluicing occurs in many languages.

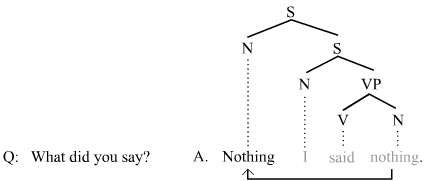

In linguistics, ellipsis or an elliptical construction is the omission from a clause of one or more words that are nevertheless understood in the context of the remaining elements. There are numerous distinct types of ellipsis acknowledged in theoretical syntax. Theoretical accounts of ellipsis seek to explain its syntactic and semantic factors, the means by which the elided elements are recovered, and the status of the elided elements.

In linguistics, verb phrase ellipsis is a type of elliptical construction and a type of anaphora in which a verb phrase has been left out (elided) provided that its antecedent can be found within the same linguistic context. For example, "She will sell sea shells, and he will <sell sea shells> too" is understood as "She will sell sea shells, and he will sell sea shells too". VP-ellipsis is well-studied, particularly with regard to its occurrence in English, although certain types can be found in other languages as well.

In linguistics, coordination is a complex syntactic structure that links together two or more elements; these elements are called conjuncts or conjoins. The presence of coordination is often signaled by the appearance of a coordinator, e.g. and, or, but. The totality of coordinator(s) and conjuncts forming an instance of coordination is called a coordinate structure. The unique properties of coordinate structures have motivated theoretical syntax to draw a broad distinction between coordination and subordination. It is also one of the many constituency tests in linguistics. Coordination is one of the most studied fields in theoretical syntax, but despite decades of intensive examination, theoretical accounts differ significantly and there is no consensus on the best analysis.

Antecedent-contained deletion (ACD), also called antecedent-contained ellipsis, is a phenomenon whereby an elided verb phrase appears to be contained within its own antecedent. For instance, in the sentence "I read every book that you did", the verb phrase in the main clause appears to license ellipsis inside the relative clause which modifies its object. ACD is a classic puzzle for theories of the syntax-semantics interface, since it threatens to introduce an infinite regress. It is commonly taken as motivation for syntactic transformations such as quantifier raising, though some approaches explain it using semantic composition rules or by adoption more flexible notions of what it means to be a syntactic unit.

In linguistics, gapping is a type of ellipsis that occurs in the non-initial conjuncts of coordinate structures. Gapping usually elides minimally a finite verb and further any non-finite verbs that are present. This material is "gapped" from the non-initial conjuncts of a coordinate structure. Gapping exists in many languages, but by no means in all of them, and gapping has been studied extensively and is therefore one of the more understood ellipsis mechanisms. Stripping is viewed as a particular manifestation of the gapping mechanism where just one remnant appears in the gapped/stripped conjunct.

In linguistics, sloppy identity is an interpretive property that is found with verb phrase ellipsis where the identity of the pronoun in an elided VP is not identical to the antecedent VP.

In linguistics, immediate constituent analysis or IC analysis is a method of sentence analysis that was proposed by Wilhelm Wundt and named by Leonard Bloomfield. The process reached a full-blown strategy for analyzing sentence structure in the distributionalist works of Zellig Harris and Charles F. Hockett, and in glossematics by Knud Togeby. The practice is now widespread. Most tree structures employed to represent the syntactic structure of sentences are products of some form of IC-analysis. The process and result of IC-analysis can, however, vary greatly based upon whether one chooses the constituency relation of phrase structure grammars or the dependency relation of dependency grammars as the underlying principle that organizes constituents into hierarchical structures.

In linguistics, a catena is a unit of syntax and morphology, closely associated with dependency grammars. It is a more flexible and inclusive unit than the constituent and its proponents therefore consider it to be better suited than the constituent to serve as the fundamental unit of syntactic and morphosyntactic analysis.

Pseudogapping is an ellipsis mechanism that elides most but not all of a non-finite verb phrase; at least one part of the verb phrase remains, which is called the remnant. Pseudogapping occurs in comparative and contrastive contexts, so it appears often after subordinators and coordinators such as if, although, but, than, etc. It is similar to verb phrase ellipsis (VP-ellipsis) insofar as the ellipsis is introduced by an auxiliary verb, and many grammarians take it to be a particular type of VP-ellipsis. The distribution of pseudogapping is more restricted than that of VP-ellipsis, however, and in this regard, it has some traits in common with gapping. But unlike gapping, pseudogapping occurs in English but not in closely related languages. The analysis of pseudogapping can vary greatly depending in part on whether the analysis is based in a phrase structure grammar or a dependency grammar. Pseudogapping was first identified, named, and explored by Stump (1977) and has since been studied in detail by Levin (1986) among others, and now enjoys a firm position in the canon of acknowledged ellipsis mechanisms of English.

Stripping or bare argument ellipsis is an ellipsis mechanism that elides everything from a clause except one constituent. It occurs exclusively in the non-initial conjuncts of coordinate structures. One prominent analysis of stripping sees it as a particular manifestation of the gapping mechanism, the difference between stripping and gapping lies merely with the number of remnants left behind by ellipsis: gapping leaves two constituents behind, whereas stripping leaves just one. Stripping occurs in many languages and is a frequent occurrence in colloquial conversation. As with many other ellipsis mechanisms, stripping challenges theories of syntax in part because the elided material often fails to qualify as a constituent in a straightforward manner.

Noun ellipsis (N-ellipsis), also noun phrase ellipsis (NPE), is a mechanism that elides, or appears to elide, part of a noun phrase that can be recovered from context. The mechanism occurs in many languages like English, which uses it less than related languages.

This article describes the syntax of clauses in the English language, chiefly in Modern English. A clause is often said to be the smallest grammatical unit that can express a complete proposition. But this semantic idea of a clause leaves out much of English clause syntax. For example, clauses can be questions, but questions are not propositions. A syntactic description of an English clause is that it is a subject and a verb. But this too fails, as a clause need not have a subject, as with the imperative, and, in many theories, an English clause may be verbless. The idea of what qualifies varies between theories and has changed over time.

In linguistics, the term right node raising (RNR) denotes a sharing mechanism that sees the material to the immediate right of parallel structures being in some sense "shared" by those parallel structures, e.g. [Sam likes] but [Fred dislikes] the debates. The parallel structures of RNR are typically the conjuncts of a coordinate structure, although the phenomenon is not limited to coordination, since it can also appear with parallel structures that do not involve coordination. The term right node raising itself is due to Postal (1974). Postal assumed that the parallel structures are complete clauses below the surface. The shared constituent was then raised rightward out of each conjunct of the coordinate structure and attached as a single constituent to the structure above the level of the conjuncts, hence "right node raising" was occurring in a literal sense. While the term right node raising survives, the actual analysis that Postal proposed is not widely accepted. RNR occurs in many languages, including English and related languages.