Related Research Articles

The Ethnological Society of London (ESL) was a learned society founded in 1843 as an offshoot of the Aborigines' Protection Society (APS). The meaning of ethnology as a discipline was not then fixed: approaches and attitudes to it changed over its lifetime, with the rise of a more scientific approach to human diversity. Over three decades the ESL had a chequered existence, with periods of low activity and a major schism contributing to a patchy continuity of its meetings and publications. It provided a forum for discussion of what would now be classed as pioneering scientific anthropology from the changing perspectives of the period, though also with wider geographical, archaeological and linguistic interests.

The concept of race as a categorization of anatomically modern humans has an extensive history in Europe and the Americas. The contemporary word race itself is modern; historically it was used in the sense of "nation, ethnic group" during the 16th to 19th centuries. Race acquired its modern meaning in the field of physical anthropology through scientific racism starting in the 19th century. With the rise of modern genetics, the concept of distinct human races in a biological sense has become obsolete. In 2019, the American Association of Biological Anthropologists stated: "The belief in 'races' as natural aspects of human biology, and the structures of inequality (racism) that emerge from such beliefs, are among the most damaging elements in the human experience both today and in the past."

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism, racial inferiority, or racial superiority. Before the mid-20th century, scientific racism received credence throughout the scientific community, but it is no longer considered scientific. The division of humankind into biologically distinct groups, and the attribution of specific traits both physical and mental to them by constructing and applying corresponding explanatory models, i.e. racial theories, is sometimes called racialism, race realism, or race science by its proponents. Modern scientific consensus rejects this view as being irreconcilable with modern genetic research.

The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex is a book by English naturalist Charles Darwin, first published in 1871, which applies evolutionary theory to human evolution, and details his theory of sexual selection, a form of biological adaptation distinct from, yet interconnected with, natural selection. The book discusses many related issues, including evolutionary psychology, evolutionary ethics, evolutionary musicology, differences between human races, differences between sexes, the dominant role of women in mate choice, and the relevance of the evolutionary theory to society.

Jean Louis Armand de Quatrefages de Bréau was a French biologist.

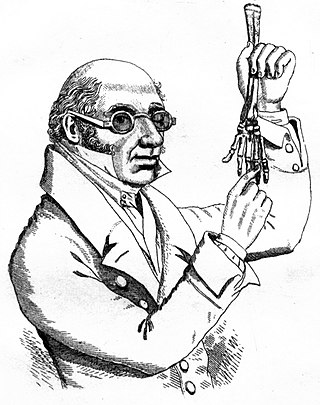

Robert Knox was a Scottish anatomist and ethnologist best known for his involvement in the Burke and Hare murders. Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, Knox eventually partnered with anatomist and former teacher John Barclay and became a lecturer on anatomy in the city, where he introduced the theory of transcendental anatomy. However, Knox's incautious methods of obtaining cadavers for dissection before the passage of the Anatomy Act 1832 and disagreements with professional colleagues ruined his career in Scotland. Following these developments, he moved to London, though this did not revive his career.

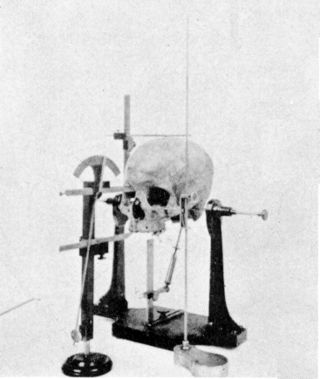

Craniometry is measurement of the cranium, usually the human cranium. It is a subset of cephalometry, measurement of the head, which in humans is a subset of anthropometry, measurement of the human body. It is distinct from phrenology, the pseudoscience that tried to link personality and character to head shape, and physiognomy, which tried the same for facial features. However, these fields have all claimed the ability to predict traits or intelligence.

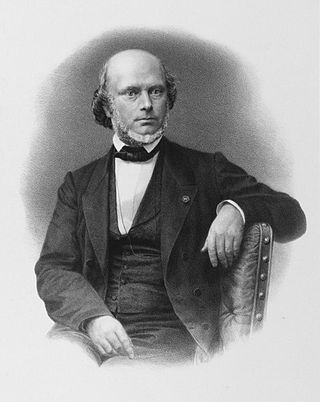

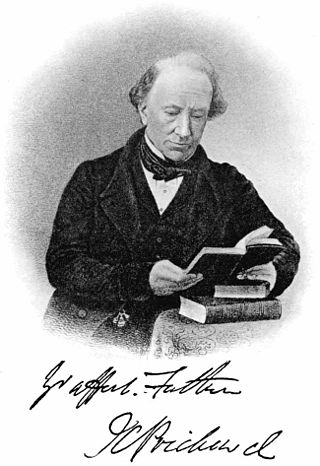

James Cowles Prichard, FRS was a British physician and ethnologist with broad interests in physical anthropology and psychiatry. His influential Researches into the Physical History of Mankind touched upon the subject of evolution. From 1845, Prichard served as a Medical Commissioner in Lunacy. He also introduced the term "senile dementia".

Samuel George Morton was an American physician, natural scientist, and writer who argued against the single creation story of the Bible, monogenism, instead supporting a theory of multiple racial creations, polygenism.

Polygenism is a theory of human origins which posits the view that the human races are of different origins (polygenesis). This view is opposite to the idea of monogenism, which posits a single origin of humanity. Modern scientific views no longer favor the polygenic model, with the monogenic "Out of Africa" hypothesis and its variants being the most widely accepted models for human origins. Historically, polygenism has been used to advance racial inequality.

Charles Gabriel Seligman FRS FRAI was a British physician and ethnologist. His main ethnographic work described the culture of the Vedda people of Sri Lanka and the Shilluk people of the Sudan. He was a professor at London School of Economics and was highly influential as the teacher of such notable anthropologists as Bronisław Malinowski, E. E. Evans-Pritchard and Meyer Fortes all of whose work overshadowed his own.

Nathaniel Southgate Shaler was an American paleontologist and geologist who wrote extensively on the theological and scientific implications of the theory of evolution, whose work is now considered scientific racism.

Josiah Clark Nott was an American surgeon and anthropologist. He is known for his studies into the etiology of yellow fever and malaria, including the theory that they originate from germs.

Monogenism or sometimes monogenesis is the theory of human origins which posits a common descent for all human races. The negation of monogenism is polygenism. This issue was hotly debated in the Western world in the nineteenth century, as the assumptions of scientific racism came under scrutiny both from religious groups and in the light of developments in the life sciences and human science. It was integral to the early conceptions of ethnology.

Negroid is an obsolete racial grouping of various people indigenous to Africa south of the area which stretched from the southern Sahara desert in the west to the African Great Lakes in the southeast, but also to isolated parts of South and Southeast Asia (Negritos). The term is derived from now-discredited conceptions of race as a biological category.

James Hunt was an anthropologist and speech therapist in London, England, during this middle of the nineteenth century. His clients included Charles Kingsley, Leo Tennyson, and Lewis Carroll author of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.

William Frédéric Edwards (1777–1842) was a French physiologist, of Jamaican background, who was also a pioneer anthropologist. He has been called "the father of ethnology in France". He is remembered largely for his principle of the permanency of physical "types." He was also a leader in the new science of "linguistique" and proposed a new branch of comparative philology based on pronunciation.

John H. Van Evrie (1814–1896) was a Canadian-born American physician and defender of slavery best known as the editor of the Weekly Day Book and the author of several books on race and slavery which reproduced the ideas of scientific racism for a popular audience. He was also the proprietor of the publishing company Van Evrie, Horton & Company. Van Evrie was described by the historian George M. Fredrickson as "perhaps the first professional racist in American history." His thought, which lacked significant scientific evidence even for the time, emphasized the inferiority of black people to white people, defended slavery as practiced in the United States and attacked abolitionism, while opposing class distinctions among white people and the oppression of the white working class. He repeatedly put "slave" and "slavery" in quotation marks, because he did not think these were the right words for enslaved Blacks.

The British explorer and Arabist Sir Richard Francis Burton (1821–1890) published over 40 books and countless articles, monographs and letters. Most of Burton's books are travel narratives or translations. His only works of original imaginative fiction are both in verse: Stone Talk (1865) and the well-known The Kasidah (1880), both of which he published under the pseudonym "Frank Baker".

Thomas Bendyshe (1827–1886) was an English barrister and academic, known as a magazine proprietor and translator.

References

- ↑ Hunt, James (1863). "Introductory Address on the Study of Anthropology". The Anthropological Review. 1 (1): 1–20. doi:10.2307/3024981. ISSN 1368-0382. JSTOR 3024981.

- ↑ Rainger, Ronald (1978). "Race, Politics, and Science: The Anthropological Society of London in the 1860s". Victorian Studies. 22 (1): 51–70. ISSN 0042-5222. JSTOR 3826928.

- ↑ RCSEd Minute Book 1847, 85-6.

- ↑ Campbell, Neil (1983). The Royal Society of Edinburgh (1783-1983). Edinburgh: Royal Society of Edinburgh. p. 72.

- ↑ Memoirs of the Anthropological Society of London, vol. 2, 1866

- ↑ Hunt 1863, p. 3.

- ↑ Hunt 1863 , p. 4

- ↑ James Hunt, President (1865), On the Negro's place in Nature, The Anthropological Review, vol. 3, pp. 53–4

- ↑ Darwin's Sacred Cause: How a hatred of slavery shaped Darwin's views on human evolution, A Desmond and J Moore, 2009 Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston/NYC; quotes from p. 332-3

- ↑ Kennedy, Dane Keith (2007). The highly civilized man : Richard Burton and the Victorian world. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02552-3.

- ↑ Sillitoe, Paul, "The Role Of Section H At The British Association For The Advancement Of Science In The History Of Anthropology", Durham Anthropology Journal, 13 (2), ISSN 1742-2930, archived from the original on 2012-10-19, retrieved 2011-06-05

- ↑ Thomas Wright (June 2004), The Life of Richard Burton, p. 65, ISBN 9781419169793

- ↑ Jorian, P. (1981), "The first anthropological society", Man, New, 1 (1): 142–144, JSTOR 2801983