William Wilberforce was a British politician, philanthropist and a leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780, and became an independent Member of Parliament (MP) for Yorkshire (1784–1812). In 1785, he underwent a conversion experience and became an evangelical Christian, which resulted in major changes to his lifestyle and a lifelong concern for reform.

The Clapham Sect, or Clapham Saints, were a group of social reformers associated with Clapham in the period from the 1780s to the 1840s. Despite the label "sect", most members remained in the established Church of England, which was highly interwoven with offices of state. However, its successors were in many cases outside of the established Anglican Church.

Augustin Barruel was a French publicist and Jesuit priest. He is now mostly known for setting forth the conspiracy theory involving the Bavarian Illuminati and the Jacobins in his book Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism published in 1797. In short, Barruel wrote that the French Revolution was planned and executed by the secret societies.

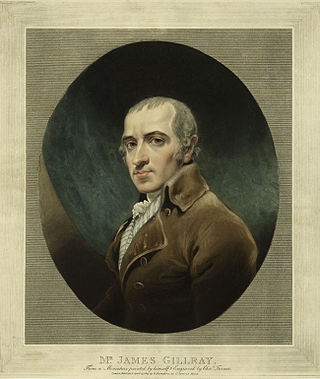

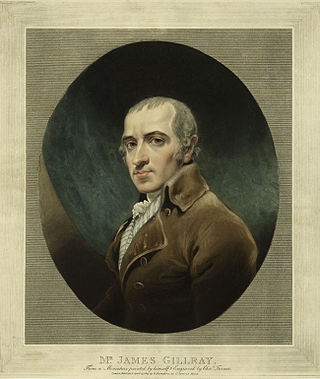

James Gillray was a British caricaturist and printmaker famous for his etched political and social satires, mainly published between 1792 and 1810. Many of his works are held at the National Portrait Gallery in London.

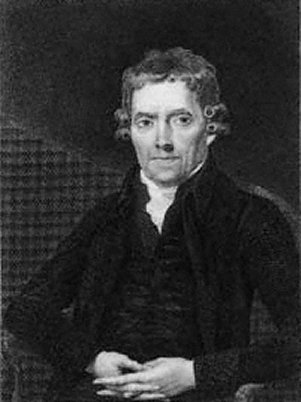

Beilby Porteus, successively Bishop of Chester and of London, was a Church of England reformer and a leading abolitionist in England. He was the first Anglican in a position of authority to seriously challenge the Church's position on slavery.

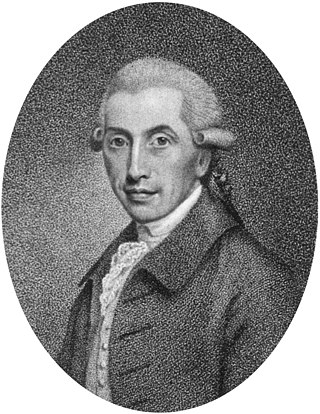

William Gifford was an English critic, editor and poet, famous as a satirist and controversialist.

Elizabeth Hamilton was a Scottish essayist, poet, satirist and novelist, who in both her prose and fiction entered into the French-revolutionary era controversy in Britain over the education and rights of women.

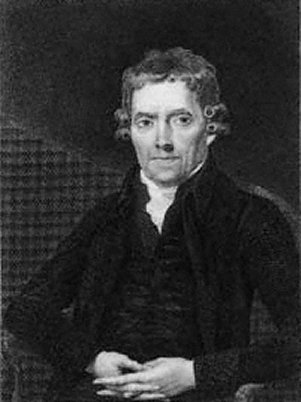

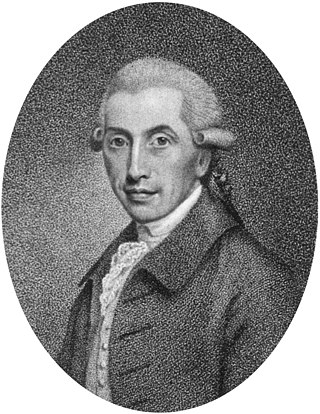

Gilbert Wakefield (1756–1801) was an English scholar and controversialist. He moved from being a cleric and academic, into tutoring at dissenting academies, and finally became a professional writer and publicist. In a celebrated state trial, he was imprisoned for a pamphlet critical of government policy of the French Revolutionary Wars; and died shortly after his release.

John Jebb (1736–1786) was an English divine, medical doctor, and religious and political reformer.

Jane West, was an English novelist who published as Prudentia Homespun and Mrs. West. She also wrote conduct literature, poetry and educational tracts.

John Robison FRSE was a British physicist and mathematician. He was a professor of natural philosophy at the University of Edinburgh.

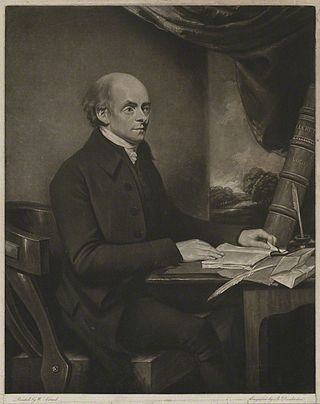

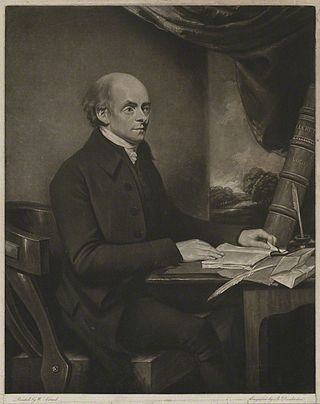

William Smith was a leading independent British politician, sitting as Member of Parliament (MP) for more than one constituency. He was an English Dissenter and was instrumental in bringing political rights to that religious minority. He was a friend and close associate of William Wilberforce and a member of the Clapham Sect of social reformers, and was in the forefront of many of their campaigns for social justice, prison reform and philanthropic endeavour, most notably the abolition of slavery. He was the grandfather of pioneer nurse and statistician Florence Nightingale and educationalist Barbara Bodichon, a founder of Girton College, Cambridge.

Anne Plumptre was an English writer and translator sometimes collaborating with her sister Annabella Plumptre. She translated several German works into English.

John Berridge was an Anglican evangelical revivalist and hymnist. J. C. Ryle wrote that as one of "the English evangelists of the eighteenth century" Berridge was "a mighty instrument for good."

Ann Jebb was an English political reformer and radical writer. She was born at Ripton-Kings, Huntingdonshire, to Dorothy Sherard and James Torkington She grew up in Huntingdonshire and was probably educated at home. She married religious and political reformer John Jebb in 1764 and fully shared his ideals. When they were first married he was lecturing at Cambridge, and she developed a reputation in university circles. Anne Plumptre was among her friends. Her writing often took the form of letters, signed with the nom de plume "Priscilla", such as the series she wrote to the London Chronicle (1772–4) during the movement of 1771 to abolish university and clerical subscription to the Thirty-nine Articles. Subsequently, in 1775, John Jebb resigned his church living, with the full support of Ann; John studied medicine and the couple later moved to London, where they were involved with a number of reformist causes such as the expansion of the franchise, opposition to the war with America, support for the French Revolution, abolitionism, and an end to legal discrimination against Roman Catholics. After she was widowed in 1786, she remained in London and continued to be politically active. Never robust, she died in 1812 and was buried with her husband.

Isaac Cruikshank was a Scottish painter and caricaturist, known for his social and political satire.

The Analytical Review was an English periodical that was published from 1788 to 1798, having been established in London by the publisher Joseph Johnson and the writer Thomas Christie. Part of the Republic of Letters, it was a gadfly publication, which offered readers summaries and analyses of the many new publications issued at the end of the eighteenth century.

The Anti-Jacobin, or, Weekly Examiner was an English newspaper founded by George Canning in 1797 and devoted to opposing the radicalism of the French Revolution. It lasted only a year, but was considered highly influential, and is not to be confused with the Anti-Jacobin Review, a publication which sprang up on its demise. The Revolution polarized British political opinion in the 1790s, with conservatives outraged at the killing of the king Louis XVI of France, the expulsion of the nobles, and the Reign of Terror. Great Britain went to war against Revolutionary France. Conservatives castigated every radical opinion in Great Britain as "Jacobin", warning that radicalism threatened an upheaval of British society. The Anti-Jacobin sentiment was expressed in print. William Gifford was its editor. Its first issue was published on 20 November 1797 and during the parliamentary session of 1797–98 it was issued every Monday.

John Gifford was an English political writer. He was born John Richards Green until changing his name at the age of 23.