Korean shamanism or Mu-ism is a religion from Korea. It is also called musok in Korean. Scholars of religion have classified it as a folk religion. There is no central authority in control of the religion and much diversity exists among practitioners.

Korean mythology is the group of myths told by historical and modern Koreans. There are two types: the written, literary mythology in traditional histories, mostly about the founding monarchs of various historical kingdoms, and the much larger and more diverse oral mythology, mostly narratives sung by shamans or priestesses (mansin) in rituals invoking the gods and which are still considered sacred today.

The People's Republic of China is officially an atheist state, but the government formally recognizes five religions: Buddhism, Taoism, Christianity, and Islam. In the early 21st century, there has been increasing official recognition of Confucianism and Chinese folk religion as part of China's cultural heritage. Chinese civilization has historically long been a cradle and host to a variety of the most enduring religio-philosophical traditions of the world. Confucianism and Taoism (Daoism), later joined by Buddhism, constitute the "three teachings" that have shaped Chinese culture. There are no clear boundaries between these intertwined religious systems, which do not claim to be exclusive, and elements of each enrich popular or folk religion. The emperors of China claimed the Mandate of Heaven and participated in Chinese religious practices. In the early 20th century, reform-minded officials and intellectuals attacked all religions as superstitious; since 1949, China has been governed by the CCP, an officially atheist party that prohibits party members from practicing religion while in office. In the culmination of a series of atheistic and anti-religious campaigns already underway since the late 19th century, the Cultural Revolution against old habits, ideas, customs, and culture, lasting from 1966 to 1976, destroyed or forced them underground. Under subsequent leaders, religious organisations have been given more autonomy.

The practice of Christianity in Korea is marginal in North Korea, but significant in South Korea, where it revolves around two of its largest branches, Protestantism and Catholicism, accounting for 8.6 million and 5.8 million members, respectively. Catholicism was first introduced during the late Joseon Dynasty period by Confucian scholars who encountered it in China. In 1603, Yi Gwang-jeong, a Korean diplomat, returned from Beijing carrying several theological books written by Matteo Ricci, an Italian Jesuit missionary to China. He began disseminating the information in the books, introducing Christianity to Korea. In 1758, King Yeongjo of Joseon officially outlawed Catholicism as an "evil practice." Catholicism was reintroduced in 1785 by Yi Seung-hun and since then French and Chinese Catholic priests were invited by the Korean Christians.

The Saemaul Undong, also known as the New Community Movement, New Village Movement, Saemaul Movement or Saema'eul Movement, was a political initiative launched on April 22, 1970 by South Korean president Park Chung-hee to modernize the rural South Korean economy. The idea was based on the Korean traditional communalism called Hyangyak and Dure (두레), which provided the rules for self-governance and cooperation in traditional Korean communities. The movement initially sought to rectify the growing disparity of the standard of living between the nation's urban centers, which were rapidly industrializing, and the small villages, which continued to be mired in poverty. Diligence, self-help and collaboration were the slogans to encourage community members to participate in the development process. The early stage of the movement focused on improving the basic living conditions and environments, whereas later projects concentrated on building rural infrastructure and increasing community income. Though hailed as a great success by force in the 1970s, the movement lost momentum during the 1980s due to the unexpected assassination of Park Chung-hee.

Christianity in China has been present since the early medieval period and it has gained a significant amount of influence during the last 200 years.

Asian witchcraft encompasses various types of witchcraft practices across Asia. In ancient times, magic played a significant role in societies such as ancient Egypt and Babylonia, as evidenced by historical records. In the Middle East, references to magic can be found in the Torah, where witchcraft is condemned due to its association with belief in magic, as it is within other Abrahamic religions.

Indigenous Philippine folk religions are the distinct native religions of various ethnic groups in the Philippines, where most follow belief systems in line with animism. Generally, these indigenous folk religions are referred to as Anito or Anitism or the more modern and less ethnocentric Dayawism, where a set of local worship traditions are devoted to the anito or diwata, terms which translate to gods, spirits, and ancestors. 0.23% of the population of the Philippines are affiliated with the indigenous Philippine folk religions according to the 2020 national census, an increase from the previous 0.19% from the 2010 census.

Throughout the ages, there have been various popular religious traditions practiced on the Korean peninsula. The oldest indigenous religion of Korea is the Korean folk religion, which has been passed down from prehistory to the present. Buddhism was introduced to Korea from China during the Three Kingdoms era in the fourth century, and the religion pervaded the culture until the Joseon Dynasty when Confucianism was established as the state philosophy. During the Late Joseon Dynasty, in the 19th century, Christianity began to gain a foothold in Korea. While both Christianity and Buddhism would play important roles in the resistance to the Japanese occupation of Korea in the first half of the 20th century, only about 4% of Koreans were members of a religious organization in 1940.

There are no known official statistics of religions in North Korea. Officially, North Korea is an atheist state, although its constitution guarantees free exercise of religion, provided that religious practice does not introduce foreign forces, harm the state, or harm the existing social order. Based on estimates from the late 1990s and the 2000s, North Korea is mostly irreligious, with the main religions being Shamanism and Chondoism. There are small communities of Buddhists and Christians. Chondoism is represented in politics by the Party of the Young Friends of the Heavenly Way, and is regarded by the government as Korea's "national religion" because of its identity as a minjung (popular) and "revolutionary anti-imperialist" movement.

Many adherents of Buddhism have experienced religious persecution because of their adherence to the Buddhist practice, including unwarranted arrests, imprisonment, beating, torture, and/or execution. The term also may be used in reference to the confiscation or destruction of property, temples, monasteries, centers of learning, meditation centers, historical sites, or the incitement of hatred towards Buddhists.

Religion in South Korea is diverse. A substantial number of South Koreans have no religion. Christianity and Buddhism are the dominant confessions among those who affiliate with a formal religion. Buddhism and Confucianism play an influential role in the lives of many South Korean people. Buddhism, which arrived in Korea in 372 AD, has thousands of temples built across the country.

According to a 2021 Gallup Korea poll, 17% of South Koreans identify as Protestant; this is about 8.5 million people. About two-thirds of these are Presbyterians. Presbyterians in South Korea worship in over 100 different Presbyterian denominational churches who trace their history back to the United Presbyterian Assembly.

Mu (Korean: 무) is the Korean term for a shaman in Korean shamanism. Korean shamans hold rituals called gut for the welfare of the individuals and the society.

Northeast China folk religion is the variety of Chinese folk religion of northeast China, characterised by distinctive cults original to Hebei and Shandong, transplanted and adapted by the Han Chinese settlers of Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang since the Qing dynasty. It is characterised by terminology, deities and practices that are different from those of central and southern Chinese folk religion. Many of these patterns derive from the interaction of Han religion with Manchu shamanism.

Religion in Inner Mongolia is characterised by the diverse traditions of Mongolian-Tibetan Buddhism, Chinese Buddhism, the Chinese traditional religion including the traditional Chinese ancestral religion, Taoism, Confucianism and folk religious sects, and the Mongolian native religion. The region is inhabited by a majority of Han Chinese and a substantial minority of Southern Mongols, so that some religions follow ethnic lines.

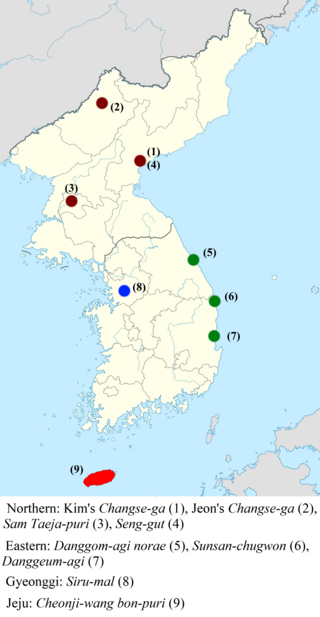

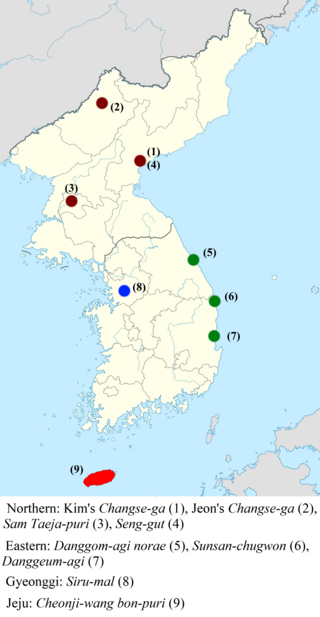

Korean creation narratives are Korean shamanic narratives which recount the mythological beginnings of the universe. They are grouped into two categories: the eight narratives of mainland Korea, which were transcribed by scholars between the 1920s and 1980s, and the Cheonji-wang bon-puri narrative of southern Jeju Island, which exists in multiple versions and continues to be sung in its ritual context today. The mainland narratives themselves are subdivided into four northern and three eastern varieties, along with one from west-central Korea.

Life replacement narratives or life extension narratives refer to three Korean shamanic narratives chanted during religious rituals, all from different regional traditions of mythology but with a similar core story: the Menggam bon-puri of the Jeju tradition, the Jangja-puri of the Jeolla tradition, and the Honswi-gut narrative of the South Hamgyong tradition. As oral literature, all three narratives exist in multiple versions.

The mengdu, also called the three mengdu and the three mengdu of the sun and moon, are a set of three kinds of brass ritual devices—a pair of knives, a bell, and divination implements—which are the symbols of shamanic priesthood in the Korean shamanism of southern Jeju Island. Although similar ritual devices are found in mainland Korea, the religious reverence accorded to the mengdu is unique to Jeju.

Gongsim is a legendary Korean princess of the Goryeo dynasty said to have been struck with sinbyeong, an illness which can only be cured by initiation into shamanism. According to the myth, she joined the shamanic priesthood at Namsan Mountain in Seoul, and introduced the shamanic religion to Korea or to parts of Korea.