Operation Peter Pan was a clandestine exodus of over 14,000 unaccompanied Cuban minors ages 6 to 18 to the United States over a two-year span from 1960 to 1962. They were sent after parents feared that Fidel Castro and the Communist party were planning to terminate parental rights and place minors in communist indoctrination centers, commonly referred to as the Patria Potestad.

The Bay of Pigs Invasion was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in 1961 by Cuban exiles, covertly financed and directed by the United States. It was aimed at overthrowing Fidel Castro's communist government. The operation took place at the height of the Cold War, and its failure influenced relations between Cuba, the United States, and the Soviet Union.

The Venceremos Brigade is an international organization founded in 1969 by members of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and officials of the Republic of Cuba. It was formed as a coalition of young people to show solidarity with the Cuban Revolution by working side by side with Cuban workers, challenging U.S. policies towards Cuba, including the United States embargo against Cuba. The yearly brigade trips, which as of 2010 have brought more than 9,000 people to Cuba, continue today and are coordinated with the Pastors For Peace Friendship Caravans to Cuba. The 48th Brigade travelled to Cuba in July 2017.

Omega 7 was an anti-Castro Cuban group based in Florida and New York made up of Cuban exiles whose stated goal was to overthrow Fidel Castro. The group had fewer than 20 members. According to the Global Terrorism Database, Omega 7 was responsible for at least 55 known anti-Castro attacks over the span of eight years with a majority of them being bombs. The group also took part in multiple high-profile murders and assassination attempts and has committed four known murders. Among their assassinations was Felix Garcia Rodriguez, a Cuban delegate who was gunned down on the 6th anniversary of the group. The group had conspired to assassinate Fidel Castro during the Cuban leader's visit to the United Nations in 1979.

The Cuban Project, also known as Operation Mongoose, was an extensive campaign of terrorist attacks against civilians and covert operations carried out by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency in Cuba. It was officially authorized on November 30, 1961 by U.S. President John F. Kennedy. The name Operation Mongoose had been agreed at a prior White House meeting on November 4, 1961. The operation was run out of JM/WAVE, a major secret United States covert operations and intelligence gathering station established a year earlier in Miami, Florida. It was led by United States Air Force General Edward Lansdale on the military side and William King Harvey at the CIA and went into effect after the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion.

The Cuban exodus is the mass emigration of Cubans from the island of Cuba after the Cuban Revolution of 1959. Throughout the exodus millions of Cubans from diverse social positions within Cuban society became disillusioned with life in Cuba and decided to emigrate in various emigration waves.

Alpha 66 is an anti-Castro paramilitary organization. The group was originally formed by Cuban exiles in the early 1960s and was most active in the late 1970s and 1980s. Its activities declined in the 1980s. Historian Alan McPherson describes it as a terrorist organization.

The Coordination of United Revolutionary Organizations was a militant group responsible for a number of terrorist activities directed at the Cuban government of Fidel Castro. It was founded by a group that included Orlando Bosch and Luis Posada Carriles, both of whom worked with the CIA at various times, and was composed chiefly of Cuban exiles opposed to the Castro government. It was formed in 1976 as an umbrella group for a number of anti-Castro militant groups. Its activities included a number of bombings and assassinations, including the killing of human-rights activist Orlando Letelier in Washington, D.C., and the bombing of Cubana Flight 455 which killed 73 people.

Relations between Cuba and Venezuela were established in 1902. The relationship deteriorated in the 1960s and Venezuela broke relations in late 1961 following the Betancourt Doctrine policy of not having ties with governments that had come to power by non-electoral means. A destabilizing factor was the Cuban support for the antigovernment guerrilla force that operates in remote rural areas. Venezuela broke off relations with Cuba after the Machurucuto invasion in 1967, when Cuban trained guerrillas landed in Venezuela seeking to recruit guerrillas and overthrow the government of Raúl Leoni. Relations were reestablished in 1974.

Dr. Bernardo Benes Baikowitz was a prominent Jewish Cuban lawyer, banker, journalist and civic leader, who was responsible for freeing 3,600 Cuban political prisoners in 1978.

Alfredo Joaquin González Durán is a Cuban-born lawyer and an advocate for dialogue as a way to bring regime change in Cuba. His views are considered controversial in some parts of the Cuban exile community in Miami.

Sandy (Alexandra) Pollack (1948–1985) was an American Communist activist. She is best known for her involvement in the founding of the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador (CISPES), which was the focus of two highly controversial FBI investigations. One addressed possible violations of the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), in which her personal contact with Farid Handal, brother of Salvadoran Communist leader Shafik, was called into question. The other concerned alleged tangible support of terrorist activities perpetrated by or on behalf of the Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional, FMLN and Frente Democrático Revolucionario FDR under the guise of international solidarity. The first case was dropped for lack of evidence. She was killed in a plane crash before the second case was settled.

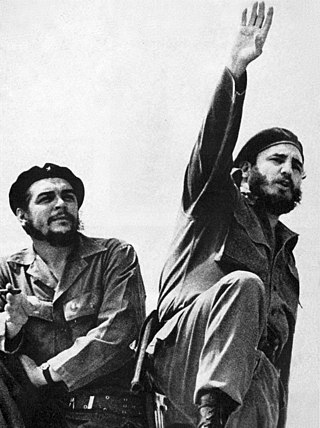

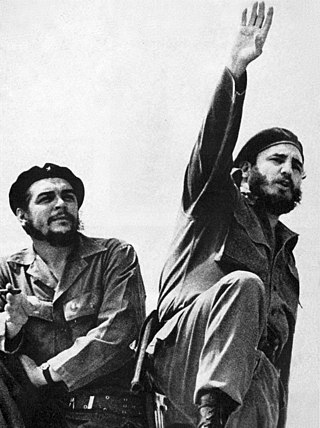

The Cuban Revolution was not only fought by armed rebels on the battlefield but also through the propaganda campaigns designed and orchestrated by Fidel Castro and his rebel comrades. Propaganda in Cuba during the revolution included Castro's use of personal interviews with journalists, radio broadcasts and publicity seeking operations that contributed significantly to the victory of the rebels over Fulgencio Batista's government and provided insight into the successful propaganda campaign established by Castro after gaining power. The limited yet successful revolutionary propaganda apparatus transitioned into what Castro has called "one of the most potent weapons in his foreign policy arsenal." Today the Cuban government maintains an intricate propaganda machine that includes a global news agency, magazines, newspapers, broadcasting facilities, publishing houses, front groups, and other miscellaneous organizations that all stem from the modest beginnings of Castro's revolutionary propaganda machine.

Lourdes Casal was an important poet and activist for the Cuban community. She was internationally known for her contributions to psychology, writing, and Cuban politics. Born and raised in Cuba, she sought exile in New York because of Cuban communist rule. Casal received a master's degree in psychology in 1962 and later, a doctorate in 1975 from the New School for Social Research. She wrote the book El caso Padilla: literatura y revolucion en Cuba, which illustrated the failing relationship between writers and Cuban officials. A year later, she co-founded a journal named Nueva Generation which focused on creating dialogue on relationships between Cubans living abroad and on the island. Casal earned notoriety by attempting to reconcile Cuban exiles in the United States. She was instrumental in organizing a dialogue between Cuban immigrants and Fidel Castro, which led to the release of thousands of Cuban prisoners. She was the first Cuban-American to receive the Casa de las Américas Prize, which was awarded to her posthumously in 1981.

The consolidation of the Cuban Revolution is a period in Cuban history typically defined as starting in the aftermath of the revolution in 1959 and ending in the first congress of the Communist Party of Cuba 1975, which signified the final political solidifaction of the Cuban revolutionaries' new government. The period encompasses early domestic reforms, human rights violations continuing under the new regime, growing international tensions, and politically climaxed with the failure of the 1970 sugar harvest.

The emigration of Cubans, from the 1959 Cuban Revolution to October of 1962, has been dubbed the Golden exile and the first emigration wave in the greater Cuban exile. The exodus was referred to as the "Golden exile" because of the mainly upper and middle class character of the emigrants. After the success of the revolution various Cubans who had allied themselves or worked with the overthrown Batista regime fled the country. Later as the Fidel Castro government began nationalizing industries many Cuban professionals would flee the island. This period of the Cuban exile is also referred to as the Historical exile, mainly by those who emigrated during this period.

A dialoguero is a label for a person who wants to open negotiations with the Cuban government. The label was coined as an epithet by hard-line anti-communist Cuban exiles.

In 1978 negotiations known as El Diálogo occurred between Cuban exile groups and the Cuban government that resulted in the release of political prisoners.

Sandra Levinson is the executive director and co-founder of the nonprofit Center for Cuban Studies, and the founder and curator of the Cuban Art Space gallery.

Gusano is a pejorative term used to refer to Cubans who fled Cuba following the rise of Fidel Castro after the Cuban Revolution, although the term was later broadly expanded to include anyone who expressed anti-revolutionary views or was a political dissident. The term has connotations referring to class, with the word being used to insinuate that someone aspired to protect their wealth from redistribution following the rise of socialism in Cuba. By some reports, at one point, the term was even extended to refer to those who believed in God as a higher power than the state.