Ebla was one of the earliest kingdoms in Syria. Its remains constitute a tell located about 55 km (34 mi) southwest of Aleppo near the village of Mardikh. Ebla was an important center throughout the 3rd millennium BC and in the first half of the 2nd millennium BC. Its discovery proved the Levant was a center of ancient, centralized civilization equal to Egypt and Mesopotamia and ruled out the view that the latter two were the only important centers in the Near East during the Early Bronze Age. The first Eblaite kingdom has been described as the first recorded world power.

Mari was an ancient Semitic city-state in modern-day Syria. Its remains form a tell 11 kilometers north-west of Abu Kamal on the Euphrates River western bank, some 120 kilometers southeast of Deir ez-Zor. It flourished as a trade center and hegemonic state between 2900 BC and 1759 BC. The city was built in the middle of the Euphrates trade routes between Sumer in the south and the Eblaite kingdom and the Levant in the west.

Naram-Sin, also transcribed Narām-Sîn or Naram-Suen, was a ruler of the Akkadian Empire, who reigned c. 2254–2218 BC, and was the third successor and grandson of King Sargon of Akkad. Under Naram-Sin the empire reached its maximum strength. He was the first Mesopotamian king known to have claimed divinity for himself, taking the title "God of Akkad", and the first to claim the title "King of the Four Quarters, King of the Universe". As part of that he became city god of Akkade in the same way Enlil was city god of Nippur.

Eblaite, or Palaeo-Syrian, is an extinct East Semitic language used during the 3rd millennium BC by the populations of Northern Syria. It was named after the ancient city of Ebla, in modern western Syria. Variants of the language were also spoken in Mari and Nagar. According to Cyrus H. Gordon, although scribes might have spoken it sometimes, Eblaite was probably not spoken much, being rather a written lingua franca with East and West Semitic features.

Ibrium, also spelt Ebrium, was the vizier of Ebla for king Irkab-Damu and his successor Isar-Damu.

Ibbi-Sipish or Ibbi-Zikir was the vizier of Ebla for king Ishar-Damu for 17 years. He was the son of his predecessor, Ibrium, who had been Ishar-Damu's vizier for 15 years.

Tell Brak was an ancient city in Syria; its remains constitute a tell located in the Upper Khabur region, near the modern village of Tell Brak, 50 kilometers north-east of Al-Hasaka city, Al-Hasakah Governorate. The city's original name is unknown. During the second half of the third millennium BC, the city was known as Nagar and later on, Nawar.

Akshak was a city of ancient Sumer, situated on the northern boundary of Akkad, sometimes identified with Babylonian Upi.

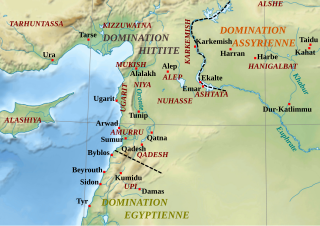

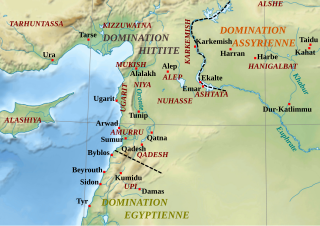

Nuhašše, also Nuhašša, was a region in northwestern Syria that flourished in the 2nd millennium BC. It was a federacy ruled by different kings who collaborated and probably had a high king. Nuhašše changed hands between different powers in the region such as Egypt, Mitanni and the Hittites. It rebelled against the latter which led Šuppiluliuma I to attack and annex the region.

The Bronze Age town of Tuttul is identified with the archaeological site of Tell Bi'a in Raqqa Governorate, northern Syria. Tell Bi'a is located near the modern city of Raqqa and the confluence of the rivers Balikh and Euphrates.

The Coastal Mountain Range also called Al-Anṣariyyah or the Nusayri mountains is a mountain range in northwestern Syria running north–south, parallel to the coastal plain. The mountains have an average width of 32 kilometres (20 mi), and their average peak elevation is just over 1,200 metres (3,900 ft) with the highest peak, Nabi Yunis, reaching 1,562 metres (5,125 ft), east of Latakia. In the north the average height declines to 900 metres (3,000 ft), and to 600 metres (2,000 ft) in the south.

The Ebla tablets are a collection of as many as 1,800 complete clay tablets, 4,700 fragments, and many thousands of minor chips found in the palace archives of the ancient city of Ebla, Syria. The tablets were discovered by Italian archaeologist Paolo Matthiae and his team in 1974–75 during their excavations at the ancient city at Tell Mardikh. The tablets, which were found in situ on collapsed shelves, retained many of their contemporary clay tags to help reference them. They all date to the period between c. 2500 BC and the destruction of the city c. 2250 BC. Today, the tablets are held in museums in the Syrian cities of Aleppo, Damascus, and Idlib.

Sarra-El also written Šarran was a prince of Yamhad who might have regained the throne after the assassination of the Hittite king Mursili I.

Armani was an ancient kingdom mentioned by Sargon of Akkad.

Vizier, is the title used by modern scholars to indicate the head of the administration in the first Eblaite kingdom. The title holder held the highest position after the king and controlled the army. During the reign of king Isar-Damu, the office of vizier became hereditary.

Ansud, was an early king (Lugal) of the second Mariote kingdom who reigned c. 2423-2416 BC. Ansud is known for warring against the Eblaites from a letter written by the later Mariote king Enna-Dagan.

Kun-Damu was a king (Malikum) of the first Eblaite kingdom ruling c. 2400 BC. The king's name is translated as "Arise, O Damu". Kun-Damu is attested in the archives of Ebla dated two generations after his reign. According to Alfonso Archi, he was a contemporary of Saʿumu of Mari. The archives of Ebla records the defeat of Mari in the 25th century BC, and based on the estimations for his reign, Kun-Damu might be the Eblaite king who inflicted this defeat upon Mari. Aleppo might have came under the rule of Ebla during his reign. Following his death, he was deified and his cult was attested in Ebla for at least 30 years after his reign.

Isar-Damu, was the king (Malikum) of the first Eblaite kingdom. Isar-Damu fought a long war with Mari which ended in Eblaite victory; he was probably the last king of the first kingdom.

Sagisu was a king (Malikum) of the first Eblaite kingdom ruling c. 2680 BC. The king's name is translated as "DN has killed".