The Egyptian language or Ancient Egyptian is an extinct Afro-Asiatic language that was spoken in ancient Egypt. It is known today from a large corpus of surviving texts which were made accessible to the modern world following the decipherment of the ancient Egyptian scripts in the early 19th century. Egyptian is one of the earliest written languages, first being recorded in the hieroglyphic script in the late 4th millennium BC. It is also the longest-attested human language, with a written record spanning over 4000 years. Its classical form is known as Middle Egyptian, the vernacular of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt which remained the literary language of Egypt until the Roman period. By the time of classical antiquity the spoken language had evolved into Demotic, and by the Roman era it had diversified into the Coptic dialects. These were eventually supplanted by Arabic after the Muslim conquest of Egypt, although Bohairic Coptic remains in use as the liturgical language of the Coptic Church.

Hapi, sometimes transliterated as Hapy, is one of the four sons of Horus in ancient Egyptian religion, depicted in funerary literature as protecting the throne of Osiris in the Underworld. Hapi was the son of Heru-ur and Isis or Serqet. He is not to be confused with another god of the same name. He is commonly depicted with the head of a hamadryas baboon, and is tasked with protecting the lungs of the deceased, hence the common depiction of a hamadryas baboon head sculpted as the lid of the canopic jar that held the lungs. Hapi is in turn protected by the goddess Nephthys. When his image appears on the side of a coffin, he is usually aligned with the side intended to face north. When embalming practices changed during the Third Intermediate Period and the mummified organs were placed back inside the body, an amulet of Hapi would be included in the body cavity.

Coptic is a language family of closely related dialects descended from the Ancient Egyptian language and historically spoken by the Copts of Egypt, starting from the third-century AD in Roman Egypt. Coptic was supplanted by Arabic as the primary spoken language of Egypt following the Muslim conquest of Egypt and was slowly replaced over the centuries. Coptic has no native speakers today, although it remains in daily use as the liturgical language of the Coptic Orthodox Church and of the Coptic Catholic Church. Innovations in grammar, phonology, and the influx of Greek loanwords distinguish Coptic from earlier periods of the Egyptian language. It is written with the Coptic alphabet, a modified form of the Greek alphabet with several additional letters borrowed from the Demotic Egyptian script.

Heka was the deification of magic and medicine in ancient Egypt. The name is the Egyptian word for "magic". According to Egyptian literature, Heka existed "before duality had yet come into being." The term ḥk3 was also used to refer to the practice of magical rituals.

The ancient Egyptians believed that a soul was made up of many parts. In addition to these components of the soul, there was the human body.

The Hymn of the Pearl is a passage of the apocryphal Acts of Thomas. In that work, originally written in Syriac, the Apostle Thomas sings the hymn while praying for himself and fellow prisoners. Some scholars believe the hymn predates the Acts, as it only appears in one Syriac manuscript and one Greek manuscript of the Acts of Thomas. The author of the Hymn is unknown, though there is a belief that it was composed by the Syriac gnostic Bardaisan from Edessa due to some parallels between his life and that of the hymn. It is believed to have been written in the 2nd century or even possibly the 1st century, and shows influences from heroic folk epics from the region.

The four sons of Horus were a group of four gods in ancient Egyptian religion, who were essentially the personifications of the four canopic jars, which accompanied mummified bodies. Since the heart was thought to embody the soul, it was left inside the body. The brain was thought only to be the origin of mucus, so it was reduced to liquid, removed with metal hooks, and discarded. This left the stomach, liver, large intestines, and lungs, which were removed, embalmed and stored, each organ in its own jar. There were times when embalmers deviated from this scheme: during the 21st Dynasty they embalmed and wrapped the viscera and returned them to the body, while the canopic jars remained empty symbols.

Sefer HaRazim is a Jewish magical text supposedly given to Noah by the angel Raziel, and passed down throughout Biblical history until it ended up in the possession of Solomon, for whom it was a great source of his wisdom and purported magical powers. Note that this is not the same work as the Sefer Raziel HaMalakh, which was given to Adam by the same angel, although both works stem from the same tradition, and large parts of Sefer HaRazim were incorporated into the Sefer Raziel under its original title.

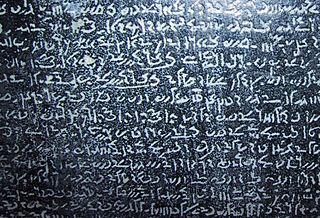

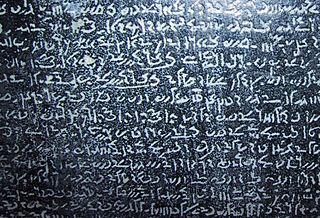

Demotic is the ancient Egyptian script derived from northern forms of hieratic used in the Nile Delta, and the stage of the Egyptian language written in this script, following Late Egyptian and preceding Coptic. The term was first used by the Greek historian Herodotus to distinguish it from hieratic and hieroglyphic scripts. By convention, the word "Demotic" is capitalized in order to distinguish it from demotic Greek.

Francis Llewellyn Griffith was an eminent British Egyptologist of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Saint Samuel the Confessor is a Coptic Orthodox saint, venerated in all Oriental Orthodox Churches. He is most famous for his torture at the hands of the Chalcedonian Byzantines, for his witness of the Arab invasion of Egypt, and for having built the monastery that carries his name in Mount Qalamoun. He carries the label "confessor" because he endured torture for his Christian faith, but was not a martyr.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Egypt face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents.

The Greek Magical Papyri is the name given by scholars to a body of papyri from Graeco-Roman Egypt, written mostly in ancient Greek, which each contain a number of magical spells, formulae, hymns, and rituals. The materials in the papyri date from the 100s BCE to the 400s CE. The manuscripts came to light through the antiquities trade, from the 1700s onward. One of the best known of these texts is the Mithras Liturgy.

Love magic is the use of magic to conjure sexual passion or romantic love. Love magic is a branch of traditional magical practice, and a long-time trope in literature and art. It is believed it can be implemented in a variety of ways, such as by written spells, dolls, charms, amulets, potions, or rituals. It is attested to on cuneiform tablets from the ancient Near East, in ancient Egyptian texts, in the Greco-Roman world, the Middle Ages, and up to the present day. It is used in the story of Heracles and Deianeira and in Gaetano Donizetti's 1832 opera The Elixir of Love, Richard Wagner's 1865 opera Tristan and Isolde, and Manuel de Falla's 1915 ballet El amor brujo, Carmella Madamé Schwering Love Spells

Homosexuality in ancient Egypt is a disputed subject within Egyptology. Historians and egyptologists alike debate what kinds of views the ancient Egyptians' society fostered about homosexuality. Only a handful of direct clues survive, and many possible indications are vague and subject to speculation.

The "Mithras Liturgy" is a text from the Great Magical Papyrus of Paris, part of the Greek Magical Papyri, numbered PGM IV.475-834. The modern name by which the text is known originated in 1903 with Albrecht Dieterich, its first translator, based on the invocation of Helios Mithras as the god who will provide the initiate with a revelation of immortality. The text is generally considered a product of the religious syncretism characteristic of the Hellenistic and Roman Imperial era, as were the Mithraic mysteries themselves. Some scholars have argued that it has no direct connection to particular Mithraic ritual. Others consider it an authentic reflection of Mithraic liturgy, or view it as Mithraic material reworked for the syncretic tradition of magic and esotericism.

Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 120 contains two letters, written in Greek and discovered in Oxyrhynchus. The manuscript was written on papyrus in the form of a sheet. The document was written in the 4th century. Currently it is housed at Haileybury College in Hertford Heath.

The Egyptian Book of the Dead of Qenna is a papyrus document housed at the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden. One of several thousand papyri containing material drawn from Book of the Dead funerary texts, Qenna uniquely includes a passage that describes a deceased person’s activity in an afterlife location it calls the “house of hearts.” While the house of hearts is mentioned in at least two tomb inscriptions, Qenna treats it in more detail. The passage appears as an addendum within Spell 151 of the Book of the Dead:

"You will enter the house of hearts, the place which is full of hearts. You will take the one that is yours and put it in its place, without your hand being hindered. Your foot will not be stopped from walking. You will not walk upside down. You will walk upright."

The Philinna Papyrus is part of a collection of ancient Greek spells written in hexameter verse. Three spells are partially preserved on the papyrus. One is a cure for headache, one probably for a skin condition, and the purpose of the third spell is uncertain. Two fragments of the papyrus survive, in the collections of the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, and the Berlin State Museums.