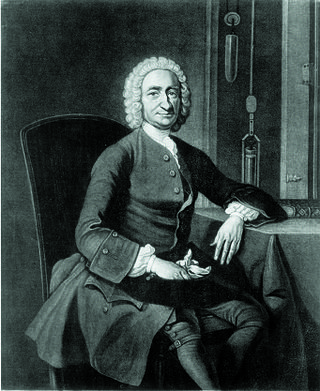

John Flamsteed was an English astronomer and the first Astronomer Royal. His main achievements were the preparation of a 3,000-star catalogue, Catalogus Britannicus, and a star atlas called Atlas Coelestis, both published posthumously. He also made the first recorded observations of Uranus, although he mistakenly catalogued it as a star, and he laid the foundation stone for the Royal Greenwich Observatory.

The Royal Observatory, Greenwich is an observatory situated on a hill in Greenwich Park in south east London, overlooking the River Thames to the north. It played a major role in the history of astronomy and navigation, and because the Prime Meridian passed through it, it gave its name to Greenwich Mean Time, the precursor to today's Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). The ROG has the IAU observatory code of 000, the first in the list. ROG, the National Maritime Museum, the Queen's House and the clipper ship Cutty Sark are collectively designated Royal Museums Greenwich.

A prime meridian is an arbitrarily-chosen meridian in a geographic coordinate system at which longitude is defined to be 0°. Together, a prime meridian and its anti-meridian form a great circle. This great circle divides a spheroid, like Earth, into two hemispheres: the Eastern Hemisphere and the Western Hemisphere. For Earth's prime meridian, various conventions have been used or advocated in different regions throughout history. Earth's current international standard prime meridian is the IERS Reference Meridian. It is derived, but differs slightly, from the Greenwich Meridian, the previous standard.

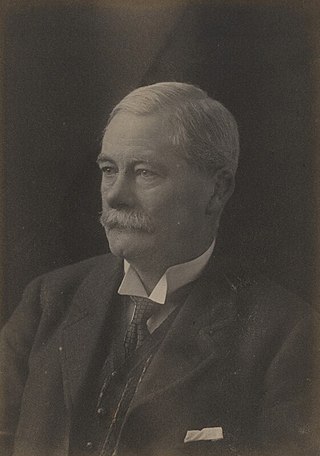

John Couch Adams was a British mathematician and astronomer. He was born in Laneast, near Launceston, Cornwall, and died in Cambridge.

Sir George Biddell Airy was an English mathematician and astronomer, as well as the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics from 1826 to 1828 and the seventh Astronomer Royal from 1835 to 1881. His many achievements include work on planetary orbits, measuring the mean density of the Earth, a method of solution of two-dimensional problems in solid mechanics and, in his role as Astronomer Royal, establishing Greenwich as the location of the prime meridian.

Sir Frank Watson Dyson, KBE, FRS, FRSE was an English astronomer and the ninth Astronomer Royal who is remembered today largely for introducing time signals ("pips") from Greenwich, England, and for the role he played in proving Einstein's theory of general relativity.

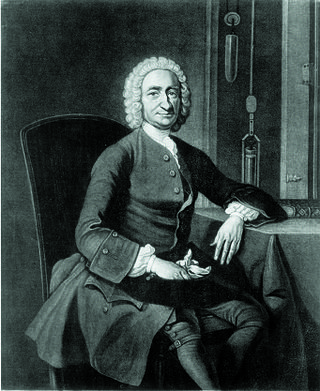

George Graham, FRS was an English clockmaker, inventor, and geophysicist, and a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Herbert Hall Turner was a British astronomer and seismologist.

Sir Harold Spencer Jones KBE FRS FRSE PRAS was an English astronomer. He became renowned as an authority on positional astronomy and served as the tenth Astronomer Royal for 23 years. Although born "Jones", his surname became "Spencer Jones".

The planet Neptune was mathematically predicted before it was directly observed. With a prediction by Urbain Le Verrier, telescopic observations confirming the existence of a major planet were made on the night of September 23–24, 1846, at the Berlin Observatory, by astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle, working from Le Verrier's calculations. It was a sensational moment of 19th-century science, and dramatic confirmation of Newtonian gravitational theory. In François Arago's apt phrase, Le Verrier had discovered a planet "with the point of his pen".

The history of longitude describes the centuries-long effort by astronomers, cartographers and navigators to discover a means of determining the longitude of any given place on Earth. The measurement of longitude is important to both cartography and navigation. In particular, for safe ocean navigation, knowledge of both latitude and longitude is required, however latitude can be determined with good accuracy with local astronomical observations.

Richard Towneley was an English mathematician, natural philosopher and astronomer, resident at Towneley Hall, near Burnley in Lancashire. His uncle was the antiquarian and mathematician Christopher Towneley (1604–1674).

Edwin Dunkin FRS, FRAS was a British astronomer and the president of the Royal Astronomical Society and the Royal Institution of Cornwall.

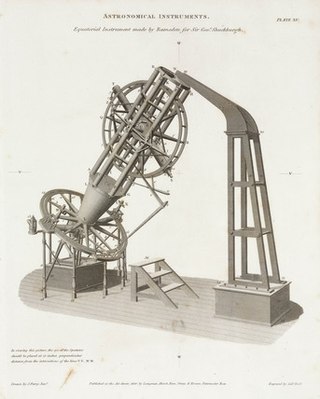

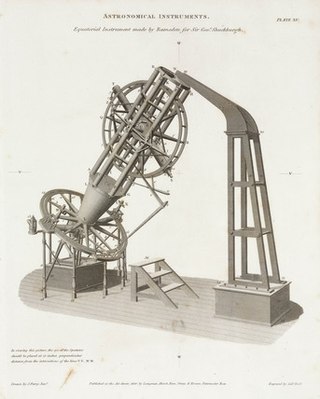

The Shuckburgh telescope or Shuckburgh equatorial refracting telescope was a 4.1 inches (10.4 cm) diameter aperture telescope on an equatorial mount completed in 1791 for Sir George Shuckburgh (1751–1804) in Warwickshire, England, and built by British instrument maker Jesse Ramsden (1735–1800). It was transferred to the Royal Observatory, Greenwich in 1811 and the London Science Museum in 1929. Even though it has sometimes not been regarded as particularly successful, its design was influential. It was one of the larger achromatic doublet telescopes at the time, and one of the largest to have an equatorial mount. It was also known as the eastern equatorial for its location.

Robert Grant, FRS was a Scottish astronomer.

The 1874 Transit of Venus Expedition to Hawaii was an astronomical expedition by British scientists to observe the December 8 transit of Venus at three separate observing sites in the Hawaiian Islands, then known as the Sandwich Islands. It was one of five 1874 transit expeditions organized by George Biddell Airy, Astronomer Royal at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich. The purpose of the expedition was to obtain an accurate estimate of the astronomical unit (AU), the distance from the Earth to the Sun, by measuring solar parallax. Previous efforts to obtain a precise value of an AU in 1769 had been hampered by the black drop effect. There is a collection of papers relating to this expedition at the Cambridge Digital Library.

Alice Everett was a British astronomer and engineer who grew up in Belfast. Everett is best known for being the first woman to be paid for astronomical work at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, when she began her employment at the observatory January 1890. In 1903 she was the first woman to have a paper published by the Physical Society of London. She also contributed to the fields of optics and early television.

George Lyon Tupman FRAS was the Chief Astronomer for the British astronomical expedition to Hawaii to observe the 1874 transit of Venus.

Thomas Glanville Taylor was an English astronomer who worked extensively at the Madras Observatory and produced the Madras Catalogue of Stars from around 1831 to 1839.

The Greenwich 28-inch refractor is a telescope at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, where it was first installed in 1893. It is a 28-inch ( 71 cm) aperture objective lens telescope, otherwise known as a refractor, and was made by the telescope maker Sir Howard Grubb. The achromatic lens was made Grubb from Chance Brothers glass. The mounting is older however and dates to the 1850s, having been designed by Royal Observatory director George Airy and the firm Ransomes and Simms. The telescope is noted for its spherical dome which extends beyond the tower, nicknamed the "onion" dome. Another name for this telescope is "The Great Equatorial" which it shares with the building, which housed an older but smaller telescope previously.