The video game crash of 1983 was a large-scale recession in the video game industry that occurred from 1983 to 1985, primarily in the United States. The crash was attributed to several factors, including market saturation in the number of video game consoles and available games, many of which were of poor quality. Waning interest in console games in favor of personal computers also played a role. Home video game revenue peaked at around $3.2 billion in 1983, then fell to around $100 million by 1985. The crash abruptly ended what is retrospectively considered the second generation of console video gaming in North America. To a lesser extent, the arcade video game market also weakened as the golden age of arcade video games came to an end.

A regional lockout is a class of digital rights management preventing the use of a certain product or service, such as multimedia or a hardware device, outside a certain region or territory. A regional lockout may be enforced through physical means, through technological means such as detecting the user's IP address or using an identifying code, or through unintentional means introduced by devices only supporting certain regional technologies.

Accolade, Inc. was an American video game developer and publisher based in San Jose, California. The company was founded as Accolade in 1984 by Alan Miller and Bob Whitehead, who had previously co-founded Activision in 1979. The company became known for numerous sports game series, including HardBall!, Jack Nicklaus and Test Drive.

Software copyright is the application of copyright in law to machine-readable software. While many of the legal principles and policy debates concerning software copyright have close parallels in other domains of copyright law, there are a number of distinctive issues that arise with software. This article primarily focuses on topics particular to software.

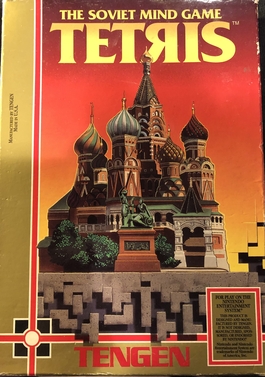

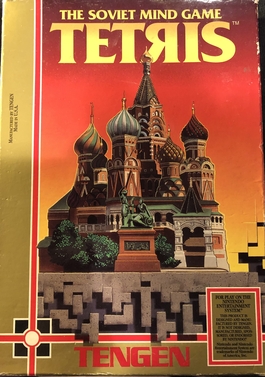

Tengen Inc. was an American video game publisher and developer that was created by the arcade game manufacturer Atari Games for publishing computer and console games. It had a Japanese subsidiary named Tengen Ltd..

Tetris is a puzzle game developed by Atari Games and originally released for arcades in 1988. Based on Alexey Pajitnov's Tetris, Atari Games' version features the same gameplay as the computer editions of the game, as players must stack differently shaped falling blocks to form and eliminate horizontal lines from the playing field. The game features several difficulty levels and two-player simultaneous play.

A video game clone is either a video game or a video game console very similar to, or heavily inspired by, a previous popular game or console. Clones are typically made to take financial advantage of the popularity of the cloned game or system, but clones may also result from earnest attempts to create homages or expand on game mechanics from the original game. An additional motivation unique to the medium of games as software with limited compatibility, is the desire to port a simulacrum of a game to platforms that the original is unavailable for or unsatisfactorily implemented on.

The Sega Genesis, also known as the Mega Drive outside North America, is a 16-bit fourth generation home video game console developed and sold by Sega. It was Sega's third console and the successor to the Master System. Sega released it in 1988 in Japan as the Mega Drive, and in 1989 in North America as the Genesis. In 1990, it was distributed as the Mega Drive by Virgin Mastertronic in Europe, Ozisoft in Australasia, and Tectoy in Brazil. In South Korea, it was distributed by Samsung Electronics as the Super Gam*Boy and later the Super Aladdin Boy.

In video gaming parlance, a conversion is the production of a game on one computer or console that was originally written for another system. Over the years, video game conversion has taken form in a number of different ways, both in their style and the method in which they were converted.

A video game console emulator is a type of emulator that allows a computing device to emulate a video game console's hardware and play its games on the emulating platform. More often than not, emulators carry additional features that surpass limitations of the original hardware, such as broader controller compatibility, timescale control, easier access to memory modifications, and unlocking of gameplay features. Emulators are also a useful tool in the development process of homebrew demos and the creation of new games for older, discontinued, or rare consoles.

Lewis Galoob Toys, Inc. v. Nintendo of America, Inc. is a 1992 legal case where the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit concluded that there was no copyright infringement made by the Game Genie, a video game accessory that could alter the output of games for the Nintendo Entertainment System. The court determined that Galoob's Game Genie did not violate Nintendo's exclusive right to make derivative works of their games, because the Game Genie did not create a new permanent work. The court also found that the alterations produced by the Game Genie qualified as non-commercial fair use, and none of the alterations were supplanting demand for Nintendo's games.

In copyright law, a derivative work is an expressive creation that includes major copyrightable elements of a first, previously created original work. The derivative work becomes a second, separate work independent from the first. The transformation, modification or adaptation of the work must be substantial and bear its author's personality sufficiently to be original and thus protected by copyright. Translations, cinematic adaptations and musical arrangements are common types of derivative works.

A fan game is a video game that is created by fans of a certain topic or IP. They are usually based on one, or in some cases several, video game entries or franchises. Many fan games attempt to clone or remake the original game's design, gameplay, and characters, but it is equally common for fans to develop a unique game using another as a template. Though the quality of fan games has always varied, recent advances in computer technology and in available tools, e.g. through open source software, have made creating high-quality games easier. Fan games can be seen as user-generated content, as part of the retrogaming phenomena, and as expression of the remix culture.

The Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) is an 8-bit third-generation home video game console produced by Nintendo. It was first released in Japan in 1983 as the Family Computer (FC), commonly referred to as Famicom. It was redesigned to become the NES, which was released in American test markets on October 18, 1985, and was soon fully launched in North America and other regions.

Sega Enterprises Ltd. v. Accolade, Inc., 977 F.2d 1510, is a case in which the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit applied American intellectual property law to the reverse engineering of computer software. Stemming from the publishing of several Sega Genesis games by video game publisher Accolade, which had disassembled Genesis software in order to publish games without being licensed by Sega, the case involved several overlapping issues, including the scope of copyright, permissible uses for trademarks, and the scope of the fair use doctrine for computer code.

The Checking Integrated Circuit (CIC) is a lockout chip designed by Nintendo for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) video game console in 1985; the chip is part of a system known as 10NES, in which a key is used by the lock to both check if the game is authentic, and if the game is the same region as the console.

Sony Computer Entertainment v. Connectix Corporation, 203 F.3d 596 (2000), is a decision by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals which ruled that the copying of a copyrighted BIOS software during the development of an emulator software does not constitute copyright infringement, but is covered by fair use. The court also ruled that Sony's PlayStation trademark had not been tarnished by Connectix Corp.'s sale of its emulator software, the Virtual Game Station.

The protection of intellectual property (IP) of video games through copyright, patents, and trademarks, shares similar issues with the copyrightability of software as a relatively new area of IP law. The video game industry itself is built on the nature of reusing game concepts from prior games to create new gameplay styles but bounded by illegally direct cloning of existing games, and has made defining intellectual property protections difficult since it is not a fixed medium.

Nintendo of America, Inc. v. Blockbuster Entertainment Corp. is a 1989 legal case related to the copyright of video games, where Blockbuster agreed to stop photocopying game instruction manuals owned by Nintendo. Blockbuster publicly accused Nintendo of starting the lawsuit after being excluded from the Computer Software Rental Amendments Act, which prohibited the rental of computer software but allowed the rental of Nintendo's game cartridges. Nintendo responded that they were enforcing their copyright as an essential foundation of the video game industry.

Atari, Inc. v. North American Philips Consumer Electronics Corp., 672 F.2d 607, is one of the first legal cases applying copyright law to video games, barring sales of the game K.C. Munchkin! for its similarities to Pac-Man. Atari had licensed the commercially successful arcade game Pac-Man from Namco and Midway, to produce a version for their Atari 2600 console. Around the same time, Philips created Munchkin as a similar maze-chase game, leading Atari to sue them for copyright infringement.