Related Research Articles

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

The Pan-African Congress (PAC) was a series of eight meetings which took place on the back of the Pan-African Conference held in London in 1900. The Pan-African Congress gained a reputation as a peacemaker for decolonization in Africa and in the West Indies. It made a significant advance for the Pan-African cause. One of the group's major demands was to end colonial rule and racial discrimination. It stood against imperialism and it demanded human rights and equality of economic opportunity. The manifesto given by the Pan-African Congress included the political and economic demands of the Congress for a new world context of international cooperation and the need to address the issues facing Africa as a result of European colonization of most of the continent.

Florence Moltrop Kelley was a social and political reformer and the pioneer of the term wage abolitionism. Her work against sweatshops and for the minimum wage, eight-hour workdays, and children's rights is widely regarded today.

Edward Franklin Frazier, was an American sociologist and author, publishing as E. Franklin Frazier. His 1932 Ph.D. dissertation was published as a book titled The Negro Family in the United States (1939); it analyzed the historical forces that influenced the development of the African-American family from the time of slavery to the mid-1930s. The book was awarded the 1940 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for the most significant work in the field of race relations. It was among the first sociological works on Black people researched and written by a black person.

The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches is a 1903 work of American literature by W. E. B. Du Bois. It is a seminal work in the history of sociology and a cornerstone of African-American literature.

The talented tenth is a term that designated a leadership class of African Americans in the early 20th century. Although the term was created by white Northern philanthropists, it is primarily associated with W. E. B. Du Bois, who used it as the title of an influential essay, published in 1903. It appeared in The Negro Problem, a collection of essays written by leading African Americans and assembled by Booker T. Washington.

Richard Robert Wright Sr. was an American military officer, educator and college president, politician, civil rights advocate and banking entrepreneur. Among his many accomplishments, he founded a high school, a college, and a bank. He also founded the National Freedom Day Association in 1941.

John Gibbs St. Clair Drake was an African-American sociologist and anthropologist whose scholarship and activism led him to document much of the social turmoil of the 1960s, establish some of the first Black Studies programs in American universities, and contribute to the independence movement in Ghana. Drake often wrote about challenges and achievements in race relations as a result of his extensive research.

Rufus Early Clement was an American academic administrator and university president. He served as the sixth and longest-serving president of the historically black Atlanta University in Atlanta, Georgia.

The Philadelphia Negro is a sociological and epidemiological study of African Americans in Philadelphia that was written by W. E. B. Du Bois, commissioned by the University of Pennsylvania and published in 1899 with the intent of identifying social problems present in the African American community.

The Study of the Negro Problems, from The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, is an essay written by professor, sociologist, historian and activist W. E. B. Du Bois. It both challenges the question he poses in his The Souls of Black Folk (1903) of “How does it feel to be a problem?” and is reminiscent of the popular mindset of white people toward people of color at the time.

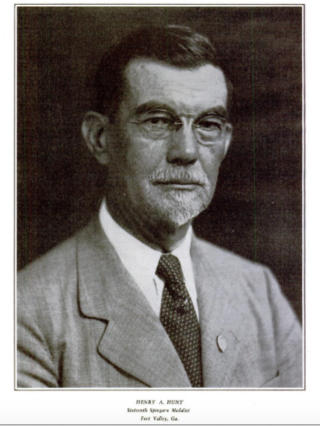

Henry Alexander Hunt was an American educator who led efforts to reach blacks in rural areas of Georgia. He was awarded the Spingarn Medal by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), as well as the Harmon Prize. In addition, he was recruited in the 1930s by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to join the president's Black Cabinet, an informal group of more than 40 prominent African Americans appointed to positions in the executive agencies.

The Exhibit of American Negroes was a sociological display within the Palace of Social Economy at the 1900 World's Fair in Paris. The exhibit was a joint effort between Daniel Murray, the Assistant Librarian of Congress, Thomas J. Calloway, a lawyer and the primary organizer of the exhibit, and W. E. B. Du Bois. The goal of the exhibition was to demonstrate progress and commemorate the lives of African Americans at the turn of the century.

The Atlanta Conference of Negro Problems was an annual conference held at Atlanta University, organized by W. E. B. Du Bois, and held every year from 1896 to 1914.

Augustus Granville Dill was born in Portsmouth, Ohio. His parents were John Dill and Elizabeth Jackson. He received his B.A. from Atlanta University in 1906, received a second B.A. from Harvard in 1908, and received his M.A. in 1909 from Harvard.

Caroline Stewart Bond Day was an American physical anthropologist, author, and educator. She was one of the first African-Americans to receive a degree in anthropology.

Lafayette M. Hershaw was a journalist, lawyer, and a clerk and law examiner for the United States General Land Office of the United States Department of the Interior. He was a key intellectual figure among African Americans in Atlanta in the 1880s and in Washington, D.C., from 1890 until his death. He was a leader of the intellectual social groups in the capital such as Bethel Literary and Historical Society and the Pen and Pencil Club. He was a strong supporter of W. E. B. Du Bois and was one of the thirteen organizers of the Niagara Movement, the forerunner to the NAACP. He was an officer of the D.C. Branch of the NAACP from its inception until 1928. He was also a founder of the Robert H. Terrell Law School and served as the school's president.

Ira De Augustine Reid was a prominent sociologist, who wrote extensively on the lives of black immigrants and communities in the United States. He was also influential in the field of educational sociology. He held faculty appointments at Atlanta University, New York University, and Haverford College, one of very few African American faculty members in the United States at white institutions during the era of "separate but equal" and the first to be awarded tenure at a prestigious Northern institution (Haverford).

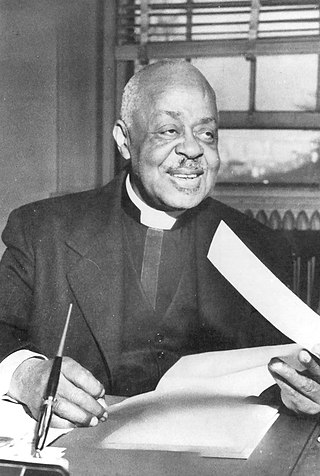

Richard Robert Wright Jr. was an American sociologist, social worker, and minister. In 1911, Wright became the first African American to earn a doctorate in sociology from an organized graduate school when he received his PhD from the University of Pennsylvania.

Gordon Blaine Hancock was a professor at Virginia Union University and a leading spokesman for African American equality in the generation before the civil rights movement.

References

- Wright, Earl II (2002). "The Atlanta Sociological Laboratory 1896-1924: a historical account of the first American school of sociology". Western Journal of Black Studies. 26 (3): 165–175.

- Wright, Earl II (2009-10-13). "Beyond W. E. B. Du Bois: A note on some of the lesser known members of the Atlanta Sociological Laboratory". Sociological Spectrum. 29 (6): 700–717. doi:10.1080/02732170903189068. ISSN 0273-2173.

- Wright, Earl II (2017). The First American School of Sociology: W.E.B. Du Bois and the Atlanta Sociological Laboratory. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-03174-1.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (10 November 1940). Written at First Congregational Church, Atlanta, GA. The Atlanta University Studies of Social Conditions among Negroes, 1896–1913 (Speech). Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (1968). The autobiography of W. E. B. Du Bois: A soliloquy on viewing my life from the last decade of its first century. New World paperback. Vol. 10. New York: International Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7178-0234-0.

- Reed, Adolph L. Jr. (1997). W. E. B. Du Bois and American political thought: Fabianism and the color line. New York: Oxford University Press USA. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-0-19-505174-2.

- Chase, Thomas N. (1896). "Mortality among negroes in cities". Atlanta University Publications. 1. Atlanta, GA: Atlanta University Press.

- Wright, Earl II; Wallace, Edward V. (2015-09-28). "Black sociology: Continuing the agenda". In Wright, Earl II; Wallace, Edward V. (eds.). The Ashgate research companion to black sociology. Ashgate research companions. Routledge. pp. 3–14. doi:10.4324/9781315612775. ISBN 978-1-4724-5676-2.