Middle English is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman Conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English period. Scholarly opinion varies, but Oxford University Press specifies the period when Middle English was spoken as being from 1100 to 1500. This stage of the development of the English language roughly followed the High to the Late Middle Ages.

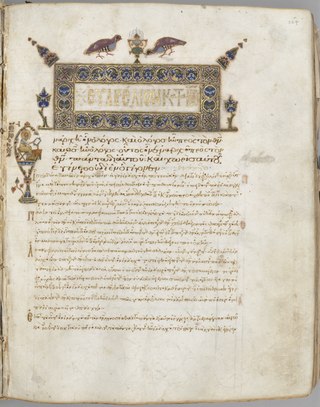

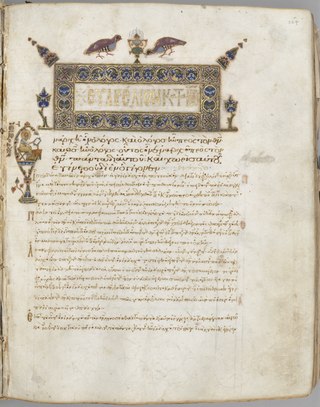

An illuminated manuscript is a formally prepared document where the text is decorated with flourishes such as borders and miniature illustrations. Illuminated manuscripts include liturgical books such as psalters, courtly literature, and documents such as proclamations.

A scriptorium was a writing room in medieval European monasteries for the copying and illuminating of manuscripts by scribes.

Sir Orfeo is an anonymous Middle English Breton lai dating from the late 13th or early 14th century. It retells the story of Orpheus as a king who rescues his wife from the fairy king. The folk song Orfeo is based on this poem.

The Old English Bible translations are the partial translations of the Bible prepared in medieval England into the Old English language. The translations are from Latin texts, not the original languages.

Cynewulf is one of twelve Old English poets known by name, and one of four whose work is known to survive today. He presumably flourished in the 9th century, with possible dates extending into the late 8th and early 10th centuries.

West Saxon is the term applied to the two different dialects Early West Saxon and Late West Saxon with West Saxon being one of the four distinct regional dialects of Old English. The three others were Kentish, Mercian and Northumbrian. West Saxon was the language of the kingdom of Wessex, and was the basis for successive widely used literary forms of Old English: the Early West Saxon of Alfred the Great's time, and the Late West Saxon of the late 10th and 11th centuries. Due to the Saxons' establishment as a politically dominant force in the Old English period, the West Saxon dialects became the strongest dialects in Old English manuscript writing.

The Vespasian Psalter is an Anglo-Saxon illuminated psalter decorated in a partly Insular style produced in the second or third quarter of the 8th century. It contains an interlinear gloss in Old English which is the oldest extant English translation of any portion of the Bible. It was produced in southern England, perhaps in St. Augustine's Abbey or Christ Church, Canterbury or Minster-in-Thanet, and is the earliest illuminated manuscript produced in "Southumbria" to survive.

Middle Persian literature is the corpus of written works composed in Middle Persian, that is, the Middle Iranian dialect of Persia proper, the region in the south-western corner of the Iranian plateau. Middle Persian was the prestige dialect during the era of Sasanian dynasty.

The Gospels of Tsar Ivan Alexander, Tetraevangelia of Ivan Alexander, or Four Gospels of Ivan Alexander is an illuminated manuscript Gospel Book, written and illustrated in 1355–1356 for Tsar Ivan Alexander of the Second Bulgarian Empire. The manuscript is regarded as one of the most important manuscripts of medieval Bulgarian culture, and has been described as "the most celebrated work of art produced in Bulgaria before it fell to the Turks in 1393".

The La Cava Bible or Codex Cavensis is a 9th-century Latin illuminated Bible, which was produced in Spain, probably in the Kingdom of Asturias during the reign of Alfonso II. The manuscript is preserved at the abbey of La Trinità della Cava, near Cava de' Tirreni in Campania, Italy, and contains 330 vellum folios which measure 320 by 260 mm.

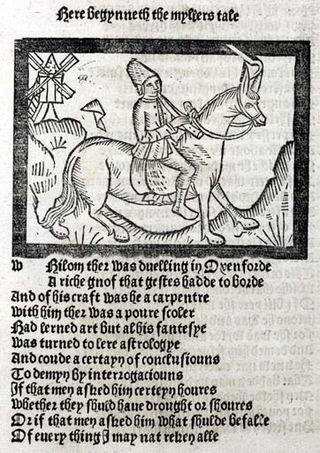

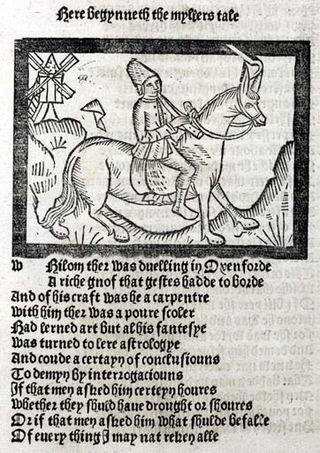

The Pilgrimage of the Soul or The Pylgremage of the Sowle was a late medieval work in English, combining prose and lyric verse, translated from Guillaume de Deguileville's Old French Le Pèlerinage de l'Âme. It circulated in manuscript in fifteenth-century England, and was among the works printed by William Caxton. One manuscript forms part of the Egerton Collection in the British Library.

The Wonders of the East is an Old English prose text, probably written around AD 1000. It is accompanied by many illustrations and appears also in two other manuscripts, in both Latin and Old English. It describes a variety of odd, magical and barbaric creatures that inhabit Eastern regions, such as Babylonia, Persia, Egypt, and India. The Wonders can be found in three extant manuscripts from the 11th and 12th centuries, the earliest of these being the famous Nowell Codex, which is also the only manuscript containing Beowulf. The Old English text was originally translated from a Latin text now referred to as De rebus in Oriente mirabilibus, and remains mostly faithful to the Latin original.

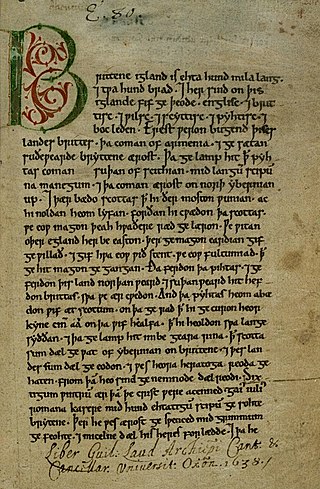

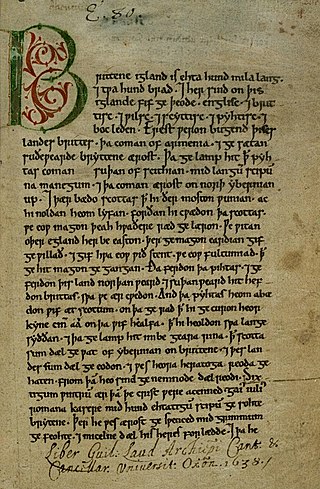

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons.

The Lambeth Homilies are a collection of homilies found in a manuscript in Lambeth Palace Library, London. The collection contains seventeen sermons and is notable for being one of the latest examples of Old English, written as it was c. 1200, well into the period of Middle English.

Hatton Gospels is the name now given to a manuscript produced in the late 12th century or early 13th century. It contains a translation of the four gospels into the West Saxon dialect of Old English. It is a nearly complete gospel book, missing only a small part of the Gospel of Luke. It is now in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, as MS Hatton 38. The fullest description of the manuscript is by Takako Kato, in Treharne, et al., eds., Production and Use of English Manuscripts, 1020-1220.

Of Arthour and of Merlin, also known as just Arthur and Merlin, is an anonymous Middle English verse romance giving an account of the reigns of Vortigern and Uther Pendragon and the early years of King Arthur's reign, in which the magician Merlin plays a large part. It can claim to be the earliest English Arthurian romance. It exists in two recensions: the first, of nearly 10,000 lines, dates from the second half of the 13th century, and the much-abridged second recension, of about 2000 lines, from the 15th century. The first recension breaks off somewhat inconclusively, and many scholars believe this romance was never completed. Arthur and Merlin's main source is the Estoire de Merlin, a French prose romance.

Stockholm, Royal Library, manuscript X. 90 is an early fifteenth-century manuscript noted for the Middle English medical texts that it contains.

The Pearl Manuscript, also known as the Gawain manuscript, is an illuminated manuscript produced somewhere in northern England in the late 14th century or the beginning of the 15th century. It is one of the best-known Middle English manuscripts, the only one containing alliterative verse solely, and the oldest surviving English manuscript to have full-page illustrations. It contains the only surviving copies of four of the masterpieces of medieval English literature: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl, Cleanness, and Patience. It has been described as "one of the greatest manuscript treasures for medieval literature", and "the most famous of all romance manuscripts".

Oxford, Bodleian Library, MSS Bodley 340 and 342 are two medieval manuscripts kept at the Bodleian Library in Oxford. They date from the early 11th century and contain a collection of Old English homilies in two volumes. From the middle of the 11th century, they were kept in Rochester, Kent. They are particularly notable for containing medieval pen trials by monks from Normandy, Flanders, Germany, and Italy, including the Old Dutch poem known as Hebban olla vogala.