Related Research Articles

Regime change is the partly forcible or coercive replacement of one government regime with another. Regime change may replace all or part of the state's most critical leadership system, administrative apparatus, or bureaucracy. Regime change may occur through domestic processes, such as revolution, coup, or reconstruction of government following state failure or civil war. It can also be imposed on a country by foreign actors through invasion, overt or covert interventions, or coercive diplomacy. Regime change may entail the construction of new institutions, the restoration of old institutions, and the promotion of new ideologies.

A military alliance is a formal agreement between nations that specifies mutual obligations regarding national security. In the event a nation is attacked, members of the alliance are often obligated to come to their defense regardless if attacked directly. Since the end of the Second World War, military alliances have usually behaved less aggressively and act more as a deterrent.

In international relations, the liberal international order (LIO), also known as the rules-based international order (RBIO), or the rules-based order (RBO), describes a set of global, rule-based, structured relationships based on political liberalism, economic liberalism and liberal internationalism since the late 1940s. More specifically, it entails international cooperation through multilateral institutions and is constituted by human equality, open markets, security cooperation, promotion of liberal democracy, and monetary cooperation. The order was established in the aftermath of World War II, led in large part by the United States.

Proponents of "democratic peace theory" argue that both liberal and republican forms of democracy are hesitant to engage in armed conflict with other identified democracies. Different advocates of this theory suggest that several factors are responsible for motivating peace between democratic states. Individual theorists maintain "monadic" forms of this theory ; "dyadic" forms of this theory ; and "systemic" forms of this theory.

International political economy (IPE) is the study of how politics shapes the global economy and how the global economy shapes politics. A key focus in IPE is on the distributive consequences of global economic exchange. It has been described as the study of "the political battle between the winners and losers of global economic exchange."

Deterrence theory refers to the scholarship and practice of how threats or limited force by one party can convince another party to refrain from initiating some other course of action. The topic gained increased prominence as a military strategy during the Cold War with regard to the use of nuclear weapons and is related to but distinct from the concept of mutual assured destruction, according to which a full-scale nuclear attack on a power with second-strike capability would devastate both parties. The central problem of deterrence revolves around how to credibly threaten military action or nuclear punishment on the adversary despite its costs to the deterrer.

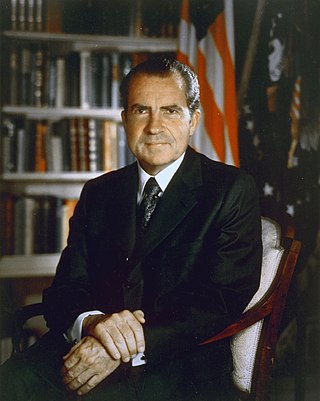

The madman theory is a political theory commonly associated with United States President Richard Nixon's foreign policy. Nixon and his administration tried to make the leaders of hostile Communist Bloc nations think he was irrational and volatile. According to the theory, those leaders would then avoid provoking the United States, fearing an unpredictable American response.

International Security is a peer-reviewed academic journal in the field of international and national security. It was founded in 1976 and is edited by the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University and published four times a year by MIT Press, both of Cambridge, Massachusetts. The current editor-in-chief is Steven E. Miller of Harvard University.

James D. Fearon is the Theodore and Francis Geballe Professor of Political Science at Stanford University; he is known for his work on the theory of civil wars, international bargaining, war's inefficiency puzzle, audience costs, and ethnic constructivism. According to a 2011 survey of International Relations scholars, Fearon is among the most influential International Relations scholars of the last twenty years. His 1995 article "Rationalist Explanations for War" is the most assigned journal article in International Relations graduate training at U.S. universities.

A diversionary foreign policy, or a diversionary war, is an international relations term that identifies a war instigated by a country's leader in order to distract its population from their own domestic strife. The concept stems from the Diversionary War Theory, which states that leaders who are threatened by domestic turmoil may initiate an international conflict in order to improve their standing. There are two primary mechanisms behind diversionary war: a manipulation of the rally 'round the flag effect, causing an increase of national fervor from the general public, and "gambling on resurrection", whereby a leader in a perilous domestic situation takes high-risk foreign policy decisions with small chance of success but with a high reward if successful.

Security studies, also known as international security studies, is an academic sub-field within the wider discipline of international relations that studies organized violence, military conflict, national security, and international security.

The capitalist peace, or capitalist peace theory, or commercial peace, posits that market openness contributes to more peaceful behavior among states, and that developed market-oriented economies are less likely to engage in conflict with one another. Along with the democratic peace theory and institutionalist arguments for peace, the commercial peace forms part of the Kantian tripod for peace. Prominent mechanisms for the commercial peace revolve around how capitalism, trade interdependence, and capital interdependence raise the costs of warfare, incentivize groups to lobby against war, make it harder for leaders to go to war, and reduce the economic benefits of conquest.

In international relations theory, the bargaining model of war is a method of representing the potential gains and losses and ultimate outcome of war between two actors as a bargaining interaction. A central puzzle that motivates research in this vein is the "inefficiency puzzle of war": why do wars occur when it would be better for all parties involved to reach an agreement that goes short of war? In the bargaining model, war between rational actors is possible due to uncertainty and commitment problems. As a result, provision of reliable information and steps to alleviate commitment problems make war less likely. It is an influential strand of rational choice scholarship in the field of international relations.

Compellence is a form of coercion that attempts to get an actor to change its behavior through threats to use force or the actual use of limited force. Compellence can be more clearly described as "a political-diplomatic strategy that aims to influence an adversary's will or incentive structure. It is a strategy that combines threats of force, and, if necessary, the limited and selective use of force in discrete and controlled increments, in a bargaining strategy that includes positive inducements. The aim is to induce an adversary to comply with one's demands, or to negotiate the most favorable compromise possible, while simultaneously managing the crisis to prevent unwanted military escalation."

In international relations, international order refers to patterned or structured relationships between actors on the international level.

Constructivism presumes that ethnic identities are shapeable and affected by politics. Through this framework, constructivist theories reassesses conventional political science dogmas. Research indicates that institutionalized cleavages and a multiparty system discourage ethnic outbidding and identification with tribal, localized groups. In addition, constructivism questions the widespread belief that ethnicity inherently inhibits national, macro-scale identification. To prove this point, constructivist findings suggest that modernization, language consolidation, and border-drawing, weakened the tendency to identify with micro-scale identity categories. One manifestation of ethnic politics gone awry, ethnic violence, is itself not seen as necessarily ethnic, since it attains its ethnic meaning as a conflict progresses.

Rational choice is a prominent framework in international relations scholarship. Rational choice is not a substantive theory of international politics, but rather a methodological approach that focuses on certain types of social explanation for phenomena. In that sense, it is similar to constructivism, and differs from liberalism and realism, which are substantive theories of world politics. Rationalist analyses have been used to substantiate realist theories, as well as liberal theories of international relations.

Gender is a subject of interest in security studies, a subfield of International relations and comparative politics. Feminist security studies and queer securities studies have provided a gender lens which shows that the study of wars, conflicts, and the institutions involved in peace and security decision-making can't be done fully without examining the role of gender and sexuality. Praising of masculine qualities has created a hierarchy of power and gender where femininity is looked down upon. Institutions reflect these power dynamics, creating systemic obstacles where women, who are seen as less capable than men, are prevented from holding high positions. Evolutionary theory and political sociology provides an understanding of how institutions like the patriarchy were created and how perceptions around national security formed between men and women.

In international relations, credibility is the perceived likelihood that a leader or a state follows through on threats and promises that have been made. Credibility is a key component of coercion, as well as the functioning of military alliances. Credibility is related to concepts such as reputation and resolve. Reputation for resolve may be a key component of credibility, but credibility is also highly context-dependent.

In international relations, coercion refers to the imposition of costs by a state on other states and non-state actors to prevent them from taking an action (deterrence) or to compel them to take an action (compellence). Coercion frequently takes the form of threats or the use of limited military force. It is commonly seen as analytically distinct from persuasion, brute force, or full-on war.

References

- ↑ "Audience Costs and the Credibility of Commitments", International Relations, Oxford University Press, 2021, doi:10.1093/obo/9780199743292-0305, ISBN 978-0-19-974329-2

- ↑ James Fearon (7 September 2013). "'Credibility' is not everything but it's not nothing either". The Monkey Cage. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

I'm drawing here on arguments about what the IR literature usually calls 'audience costs,' which are domestic political costs a leader may pay for escalating an international dispute, or for making implicit or explicit threats, and then backing down or not following through.

- ↑ Trager, Robert F. (2016). "The Diplomacy of War and Peace". Annual Review of Political Science. 19 (1): 205–228. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-051214-100534 . ISSN 1094-2939.

- 1 2 3 Downes, Alexander B.; Sechser, Todd S. (2012). "The Illusion of Democratic Credibility". International Organization. 66 (3): 457–489. doi:10.1017/S0020818312000161. ISSN 0020-8183. JSTOR 23279964. S2CID 154325372.

- 1 2 Schlesinger, Jayme R.; Levy, Jack S. (2021). "Politics, audience costs, and signalling: Britain and the 1863–4 Schleswig-Holstein crisis". European Journal of International Security. 6 (3): 338–357. doi: 10.1017/eis.2021.7 . ISSN 2057-5637.

- ↑ Fearon, James D. (September 1994). "Domestic Political Audiences and the Escalation of International Dispute". American Political Science Review. 88 (3): 577–592. doi:10.2307/2944796. JSTOR 2944796. S2CID 36315471.

- ↑ Schultz, Kenneth A. (2012). "Why We Needed Audience Costs and What We Need Now". Security Studies. 21 (3): 369–375. doi:10.1080/09636412.2012.706475. ISSN 0963-6412. S2CID 153373634.

- ↑ Tomz, Michael (2007). "Domestic Audience Costs in International Relations: An Experimental Approach". International Organization. 61 (4): 821–40. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.386.7495 . doi:10.1017/S0020818307070282. ISSN 0020-8183. S2CID 154895678.

The seminal article is Fearon 1994.

- ↑ Schultz, Kenneth A. (2001). Democracy and Coercive Diplomacy. Cambridge Studies in International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511491658. ISBN 978-0-521-79227-1.

- ↑ Gelpi, Christopher F.; Griesdorf, Michael (2001). "Winners or Losers? Democracies in International Crisis, 1918–94". American Political Science Review. 95 (3): 633–647. doi:10.1017/S0003055401003148. ISSN 0003-0554. S2CID 146346368.

- ↑ Trager, Robert F.; Vavreck, Lynn (2011). "The Political Costs of Crisis Bargaining: Presidential Rhetoric and the Role of Party". American Journal of Political Science. 55 (3): 526–545. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00521.x. ISSN 1540-5907.

- ↑ Levy, Jack S.; McKoy, Michael K.; Poast, Paul; Wallace, Geoffrey P. R. (2015). "Backing Out or Backing In? Commitment and Consistency in Audience Costs Theory". American Journal of Political Science. 59 (4): 988–1001. doi:10.1111/ajps.12197. ISSN 1540-5907.

- ↑ Tomz, Michael (2007). "Domestic Audience Costs in International Relations: An Experimental Approach". International Organization. 61 (4): 821–840. doi:10.1017/S0020818307070282. ISSN 1531-5088. S2CID 154895678.

- ↑ Kertzer, Joshua D.; Brutger, Ryan (2016). "Decomposing Audience Costs: Bringing the Audience Back into Audience Cost Theory". American Journal of Political Science. 60 (1): 234–249. doi:10.1111/ajps.12201. ISSN 1540-5907.

- ↑ Brutger, Ryan; Kertzer, Joshua D. (2018). "A Dispositional Theory of Reputation Costs". International Organization. 72 (3): 693–724. doi:10.1017/S0020818318000188. ISSN 0020-8183. S2CID 149511346.

- ↑ Evers, Miles M.; Fisher, Aleksandr; Schaaf, Steven D. (2019). "Is There a Trump Effect? An Experiment on Political Polarization and Audience Costs". Perspectives on Politics. 17 (2): 433–452. doi:10.1017/S1537592718003390. ISSN 1537-5927. S2CID 181670458.

- ↑ Gartzke, Erik; Lupu, Yonatan (2012). "Still Looking for Audience Costs". Security Studies. 21 (3): 391–397. doi:10.1080/09636412.2012.706486. ISSN 0963-6412. S2CID 219715939.

- ↑ Schultz, Kenneth A. (2001). "Looking for Audience Costs". The Journal of Conflict Resolution. 45 (1): 32–60. doi:10.1177/0022002701045001002. ISSN 0022-0027. JSTOR 3176282. S2CID 146554967.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Snyder, Jack; Borghard, Erica D. (2011). "The Cost of Empty Threats: A Penny, Not a Pound". American Political Science Review. 105 (3): 437–456. doi:10.1017/s000305541100027x. ISSN 0003-0554. S2CID 144584619.

- ↑ Slantchev, Branislav L. (2006). "Politicians, the Media, and Domestic Audience Costs". International Studies Quarterly. 50 (2): 445–477. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2006.00409.x. ISSN 0020-8833. JSTOR 3693618. S2CID 29056557.

- ↑ Potter, Philip B. K.; Baum, Matthew A. (2014). "Looking for Audience Costs in all the Wrong Places: Electoral Institutions, Media Access, and Democratic Constraint". The Journal of Politics. 76 (1): 167–181. doi:10.1017/S0022381613001230. ISSN 0022-3816. S2CID 39535209.

- ↑ Levendusky, Matthew S.; Horowitz, Michael C. (2012). "When Backing Down Is the Right Decision: Partisanship, New Information, and Audience Costs". The Journal of Politics. 74 (2): 323–338. doi:10.1017/S002238161100154X. ISSN 0022-3816.

- ↑ McManus, Roseanne W. (2017). Statements of Resolve: Achieving Coercive Credibility in International Conflict. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316756263. ISBN 978-1-107-17034-6.

- ↑ Gibler, Douglas M.; Miller, Steven V.; Little, Erin K. (2016-12-01). "An Analysis of the Militarized Interstate Dispute (MID) Dataset, 1816–2001". International Studies Quarterly. 60 (4): 719–730. doi:10.1093/isq/sqw045. ISSN 0020-8833. S2CID 151567567.

- ↑ Kertzer, Joshua D.; Renshon, Jonathan; Yarhi-Milo, Keren (2021). "How Do Observers Assess Resolve?". British Journal of Political Science. 51 (1): 308–330. doi:10.1017/S0007123418000595. ISSN 0007-1234. S2CID 197463343.

- ↑ Brown, Jonathan N.; Marcum, Anthony S. (2011). "Avoiding Audience Costs: Domestic Political Accountability and Concessions in Crisis Diplomacy". Security Studies. 20 (2): 141–170. doi:10.1080/09636412.2011.572671. ISSN 0963-6412. S2CID 144555729.

- ↑ Trachtenberg, Marc (2012). "Audience Costs: An Historical Analysis". Security Studies. 21 (1): 3–42. doi:10.1080/09636412.2012.650590. ISSN 0963-6412. S2CID 145647675.

- 1 2 Levenotoğlu, Bahar; Tarar, Ahmer (2005). "Prenegotiation Public Commitment in Domestic and International Bargaining". American Political Science Review. 99 (3): 419–433. doi:10.1017/S0003055405051750. hdl: 10161/2534 . ISSN 1537-5943. S2CID 16072285.

- ↑ Weeks, Jessica L. (2008). "Autocratic Audience Costs: Regime Type and Signaling Resolve". International Organization. 62 (1): 35–64. doi: 10.1017/S0020818308080028 . ISSN 0020-8183. JSTOR 40071874. S2CID 154432066.

- ↑ Weeks, Jessica L. P. (2014). Dictators at War and Peace. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-5296-3. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctt1287f18.

- ↑ Weiss, Jessica Chen (2014). Powerful Patriots: Nationalist Protest in China's Foreign Relations. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-938757-1.

- ↑ Kurizaki, Shuhei (2007). "Efficient Secrecy: Public versus Private Threats in Crisis Diplomacy". American Political Science Review. 101 (3): 543–558. doi:10.1017/S0003055407070396. ISSN 1537-5943. S2CID 154793333.

- 1 2 Carson, Austin (2018). Secret Wars: Covert Conflict in International Politics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-18176-9.

- 1 2 Yarhi-Milo, Keren (2013). "Tying Hands Behind Closed Doors: The Logic and Practice of Secret Reassurance". Security Studies. 22 (3): 405–435. doi:10.1080/09636412.2013.816126. ISSN 0963-6412. S2CID 153936013.

- ↑ Morrow, James D. (2000). "Alliances: Why Write Them Down?". Annual Review of Political Science. 3 (1): 63–83. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.63 . ISSN 1094-2939.

- ↑ Schwartz, Joshua A.; Blair, Christopher W. (2020). "Do Women Make More Credible Threats? Gender Stereotypes, Audience Costs, and Crisis Bargaining". International Organization. 74 (4): 872–895. doi:10.1017/S0020818320000223. ISSN 0020-8183. S2CID 225735033.

- ↑ Allee, Todd L.; Huth, Paul K. (2006). "Legitimizing Dispute Settlement: International Legal Rulings as Domestic Political Cover". American Political Science Review. 100 (2): 219–234. doi:10.1017/S0003055406062125. ISSN 1537-5943. S2CID 145146053.