The industrial firm Auergesellschaft was founded in 1892 with headquarters in Berlin. Up to the end of World War II, Auergesellschaft had manufacturing and research activities in the areas of gas mantles, luminescence, rare earths, radioactivity, and uranium and thorium compounds. In 1934, the corporation was acquired by the German corporation Degussa. In 1939, their Oranienburg plant began the development of industrial-scale, high-purity uranium oxide production. Special Soviet search teams, at the close of World War II, sent Auergesellschaft equipment, material, and staff to the Soviet Union for use in their nuclear weapon project. In 1958 Auergesellschaft merged with the Mine Safety Appliances Corporation, a multinational US corporation. Auergesellschaft became a limited corporation in 1960.

The Deutsche Gasglühlicht AG (Degea, German Gas Light Company), was founded in 1892 through the combined efforts of the Jewish entrepreneur and banker Geheimrat (Privy Councillor) Leopold Koppel and the Austrian chemist and inventor Carl Auer von Welsbach. It was the forerunner of Auergesellschaft. Their main research activities, up to the close of World War II, were on gas mantles, Luminescence, rare earths, radioactivity, and on uranium and thorium compounds. [1] [2] [3]

Geheimrat Koppel, who owned Auergesellschaft, was later intimately involved in the financing of and influencing the direction of scientific entities in Germany. Among them were the Kaiser-Wilhelm Gesellschaft (Kaiser Wilhelm Society) and its research institutes. [4] The Third Reich forced Koppel to sell Auergesellschaft, and it was purchased in 1934 by the German corporation Degussa, a large chemical company with extensive experience in the production of metals. [1] [2]

By 1901, Auergesellschaft had their first subsidiaries in Austria, the United States, and England. In 1906, the OSRAM light bulb was developed; its name was formed from the German words OSmium, for the element osmium, and WolfRAM, for the element tungsten. During the WWI the enterprise (like other mine safety companies in Europe and the US) started to manufacture gas masks for the military, and continued with industrial gas masks after that. [5] In 1920, Auergesellschaft, Siemens & Halske, and Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft (AEG) combined their electric lamp production with the formation of the company OSRAM. In 1935, Auergesellschaft developed the luminescent light. [1]

Their Oranienburg plant, 15 miles (24 km) northeast of Berlin, was constructed in 1926, and their Auer-Glaswerke was constructed in 1938. [1]

In 1958 Auergesellschaft merged with American Mine Safety Appliances Corporation; Auergesellschaft became a limited corporation in 1960 and is now known as MSA Auer. [1]

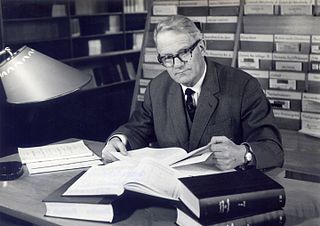

Nikolaus Riehl received his doctorate in nuclear chemistry from the University of Berlin in 1927, under the guidance of the nuclear physicist Lise Meitner and the nuclear chemist Otto Hahn. He initially took a position with Auergesellschaft, where he became an authority on luminescence. While he completed his Habilitation, he continued his industrial career at Auergesellschaft, as opposed to working in academia. From 1927, he was a staff scientist in the radiology department. From 1937, he was head of the optical engineering department. From 1939 to 1945, he was the director of the scientific headquarters. [6] [7]

Auergesellschaft had a substantial amount of “waste” uranium from which it had extracted radium. After reading a paper in 1939 by Siegfried Flügge, on the technical use of nuclear energy from uranium, [8] [9] Riehl recognized a business opportunity for the company, and, in July of that year, he went to the Heereswaffenamt (HWA, Army Ordnance Office) to discuss the production of uranium. The HWA was interested. [10] [11]

With the interest of the HWA, Riehl, and his colleague Günter Wirths, set up an industrial-scale production of high-purity uranium oxide at the Auergesellschaft plant in Oranienburg. Adding to the capabilities in the final stages of metallic uranium production were the strengths of the Degussa corporation's capabilities in metals production. [10] [12]

The Auer Oranienburg plant provided the uranium sheets and cubes for the Uranmaschine (uranium machine, i.e., nuclear reactor) experiments conducted at the Kaiser-Wilhelm Gesellschaft’s Institut für Physik (KWIP, Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Physics) and the Versuchsstelle (testing station) of the Heereswaffenamt (Army Ordnance Office) in Gottow, under the German nuclear energy project Uranverein . The G-1 experiment performed at the HWA testing station, under the direction of Kurt Diebner, had lattices of 6,800 uranium oxide cubes (about 25 tons), in the nuclear moderator paraffin. [11] [13]

Near the close of World War II, as American, British, and Russian military forces were closing in on Berlin, Riehl and some of his staff moved to a village west of Berlin, to try to assure occupation by British or American forces. In mid-May 1945, with the assistance of Riehl's colleague Karl Günter Zimmer, Russian nuclear physicists Georgy Flerov and Lev Artsimovich arrived one day in NKVD colonel's uniforms. [14] [15] The use of Russian nuclear physicists in the wake of Soviet troop advances to identify and “requisition” equipment, materiel, intellectual property and personnel useful to the Russian atomic bomb project is similar to the American Operation Alsos. The military head of Alsos was Lt. Col. Boris Pash, former head of security on the American atomic bomb effort, the Manhattan Project, and its chief scientist was the eminent physicist Samuel Goudsmit. In early 1945, the Soviets initiated an effort similar to Alsos (Russian Alsos). Forty out of fewer than 100 Russian scientists from the Soviet atomic bomb project's Laboratory No. 2 [16] went to Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia in support of acquisitions for the project. [17]

The two colonels requested that Riehl join them in Berlin for a few days, where he also met with nuclear physicist Yulii Borisovich Khariton, also in the uniform of an NKVD colonel. This sojourn in Berlin became 10 years in the Soviet Union. Riehl and his staff, including their families, were flown to Moscow on 9 July 1945. Flying Riehl and his staff to Russia demonstrates the importance the Soviets placed on the production of uranium in their atomic bomb project. Eventually, Riehl's entire laboratory was dismantled and transported to the Soviet Union. The dismantling of his laboratory began even while Riehl was being held by the Soviets in Berlin. [15] [18] [19] [20]

Work of the American Operation Alsos teams, in November 1944, uncovered leads which took them to a company in Paris that handled rare earths and had been taken over by the Auergesellschaft. This, combined with information gathered in the same month through an Alsos team in Strasbourg, confirmed that the Auergesellschaft Oranienburg plant was involved in the production of uranium and thorium metals. Since the plant was to be in the future Soviet zone of occupation and the Russian troops would arrive there before the Allies, General Leslie Groves, commander of the Manhattan Project, recommended to General George Marshall that the plant be destroyed by aerial bombardment to deny its uranium production equipment to the Russians. On Thursday, 15 March 1945, 612 B-17 Flying Fortress bombers of the Eighth Air Force, carrying out "Mission 889", dropped 1,506 tons of high-explosive and 178 tons of incendiary bombs on the plant, apparently classified as a "German Army HQ" as the target in official USAAF records of the time. [21] Riehl visited the site with the Russians and said that the facility was mostly destroyed. Riehl also recalled long after the war that the Russians knew precisely why the Americans had bombed the facility – the attack had been directed at them rather than the Germans. [22] [23] [24] [25] [26]

When a Soviet search team arrived at the Auergesellschaft facility in Oranienburg, they found nearly 100 tons of fairly pure uranium oxide. The Soviet Union took this uranium as reparations, which amounted to between 25% and 40% of the uranium taken from Germany and Czechoslovakia at the end of the war. Khariton said the uranium found there saved the Soviet Union a year on its atomic bomb project. [27] [28] [29]

Manfred baron von Ardenne was a German researcher and applied physicist and inventor. He took out approximately 600 patents in fields including electron microscopy, medical technology, nuclear technology, plasma physics, and radio and television technology. From 1928 to 1945, he directed his private research laboratory Forschungslaboratorium für Elektronenphysik. For ten years after World War II, he worked in the Soviet Union on their atomic bomb project and was awarded a Stalin Prize. Upon his return to the then East Germany, he started another private laboratory, Forschungsinstitut Manfred von Ardenne.

Nazi Germany undertook several research programs relating to nuclear technology, including nuclear weapons and nuclear reactors, before and during World War II. These were variously called Uranverein or Uranprojekt. The first effort started in April 1939, just months after the discovery of nuclear fission in Berlin in December 1938, but ended only few months later, shortly ahead of the September 1939 German invasion of Poland, for which many notable German physicists were drafted into the Wehrmacht. A second effort under the administrative purview of the Wehrmacht's Heereswaffenamt began on September 1, 1939, the day of the invasion of Poland. The program eventually expanded into three main efforts: Uranmaschine development, uranium and heavy water production, and uranium isotope separation. Eventually, the German military determined that nuclear fission would not contribute significantly to the war, and in January 1942 the Heereswaffenamt turned the program over to the Reich Research Council while continuing to fund the activity.

Karl Günter Zimmer, PhD, was a German nuclear chemist who is best known for his work in understanding the ionizing radiation on Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA).

Nikolaus Riehl was a German nuclear physicist. He was head of the scientific headquarters of Auergesellschaft. When the Russians entered Berlin near the end of World War II, he was invited to the Soviet Union, where he stayed for 10 years. For his work on the Soviet atomic bomb project, he was awarded a Stalin Prize, Lenin Prize, and Order of the Red Banner of Labor. When he was repatriated to Germany in 1955, he chose to go to West Germany, where he joined Heinz Maier-Leibnitz on his nuclear reactor staff at Technische Hochschule München (THM); Riehl made contributions to the nuclear facility Forschungsreaktor München (FRM). In 1961 he became an ordinarius professor of technical physics at THM and concentrated his research activities on solid state physics, especially the physics of ice and the optical spectroscopy of solids.

Max Christian Theodor Steenbeck was a German physicist who worked at the Siemens-Schuckertwerke in his early career, during which time he invented the betatron in 1934. He was taken to the Soviet Union after World War II, and he contributed to the Soviet atomic bomb project. In 1955, he returned to East Germany to continue a career in nuclear physics.

Heinz Barwich was a German nuclear physicist. He was deputy director of the Siemens Research Laboratory II in Berlin. At the close of World War II, he followed the decision of Gustav Hertz, to go to the Soviet Union for ten years to work on the Soviet atomic bomb project, for which he received the Stalin Prize. He was director of the Zentralinstitut für Kernforschung at Rossendorf near Dresden. For a few years he was director of the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubna, Soviet Union. In 1964 he defected to the West.

The Soviet Alsos or Russian Alsos is the western codename for an operation that took place during 1945–1946 in Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia, in order to exploit German atomic related facilities, intellectual materials, material resources, and scientific personnel for the benefit of the Soviet atomic bomb project. The contributions of the German scientists is borne out by the many USSR State Prizes and other awards given in the wake of the second Soviet atomic bomb test, a uranium-based atomic bomb; awards for uranium production and isotope separation were prevalent. Also significant in both the first Soviet atomic bomb test – a plutonium-based atomic bomb which required a uranium reactor for plutonium generation – and the second test, was the Soviet acquisition of a significant amount of uranium immediately before and shortly after the close of World War II. This saved the Soviets at least a year by their own admission.

Rudolf Heinz Pose was a German nuclear physicist who worked in the former Soviet program of nuclear weapons.

Günter Wirths was a German chemist who was an authority on uranium production, especially reactor-grade. He worked at Auergesellschaft in the production of uranium for the Heereswaffenamt and its Uranverein project. In 1945, he was sent the Soviet Union to work on the Russian atomic bomb project. When he was released from the Soviet Union, he settled in West Germany, and worked at the Degussa company.

Geheimrat Leopold Koppel was a German banker and entrepreneur. He founded the private banking house Koppel und Co., the industrial firms Auergesellschaft and OSRAM, and the philanthropic foundation the Koppel-Stiftung. He was a Senator in the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft. An endowment he made in 1911 resulted in the founding of the Kaiser-Wilhelm Institut für physikalische Chemie und Elektrochemie, and endowments from him led to the founding of and support of the Kaiser-Wilhelm Institut für Physik. As a Jew, he was a target of the Third Reich’s policy of Arisierung – the Aryanization of German businesses, which began in 1933.

Georg Robert Döpel was a German experimental nuclear physicist. He was a participant in a group known as the "first Uranverein", which was spawned by a meeting conducted by the Reichserziehungsministerium, in April 1939, to discuss the potential of a sustained nuclear reaction. He worked under Werner Heisenberg at the University of Leipzig, and he conducted experiments on spherical layers of uranium oxide surrounded by heavy water. He was a contributor to the German nuclear weapon project (Uranprojekt). In 1945, he was sent to Russia to work on the Soviet atomic bomb project. He returned to Germany in 1957, and he became professor of applied physics and director of the Institut für Angewandte Physik at the Hochschule für Elektrotechnik, now Technische Universität, in Ilmenau (Thuringia).

Alexander Siegfried Catsch was a German-Russian medical doctor and radiation biologist. Up to the end of World War II, he worked in Nikolaj Vladimirovich Timefeev-Resovskij's Abteilung für Experimentelle Genetik at the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für Hirnforschung. He was taken prisoner by the Russians at the close of World War II. Initially, he worked in Nikolaus Riehl's group at Plant No. 12 in Ehlektrostal’, but at the end of 1947 was sent to work in Sungul' at a sharashka known under the cover name Ob’ekt 0211. At the Sungul' facility, he again worked in biological research department under the direction of Timofeev-Resovskij. When Catsch returned to Germany in the mid-1950s, he fled to the West. He worked at the Biophysikalische Abteilung des Heiligenberg-Instituts and then at the Institut für Strahlenbiologie am Kernforschungszentrum Karlsruhe. While in Karlsruhe, he was also appointed, in 1962, to the newly created Lehrstuhl für Strahlenbiologie, at the Technische Hochschule Karlsruhe. In West Germany, he developed methods to extract radionucleotides from various organs.

Hans-Joachim Born was a German radiochemist trained and educated at the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für Chemie. Up to the end of World War II, he worked in Nikolaj Vladimirovich Timofeev-Resovskij's Abteilung für Experimentelle Genetik, at the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für Hirnforschung. He was taken prisoner by the Russians at the close of World War II. After rescue from the Krasnoyarsk PoW camp, he initially worked in Nikolaus Riehl's group at Plant No. 12 in Elektrostal’, Russia, but at the end of 1947 was sent to work in Sungul' at a sharashka known under the cover name Ob’ekt 0211. At the Sungul' facility, he again worked in a biological research department under the direction of Timofeev-Resovskij. Upon arrival in East Germany in the mid-1950s, Born became the director of the Institut für Angewandte Isotopenforschung in Buch, Berlin. He also completed his Habilitation at the Technische Hochschule Dresden, where he then also became a professor on the Fakultät für Kerntechnik. In 1957, he received and accepted a call to become a professor of radiochemistry at the Technische Hochschule München in West Germany.

Justus Mühlenpfordt was a German nuclear physicist. He received his doctorate from the Technische Hochschule Carolo-Wilhelmina zu Braunschweig, in 1936. He then worked in Gustav Hertz's laboratory at Siemens. In 1945, he was sent to Institute G, near Sukhumi and under the directorship of Hertz, to work on the Soviet atomic bomb project. Released from Soviet Union, Mühlenpfordt arrived in East Germany in 1955. He was appointed director of the Institut für physikalische Stofftrennung of the Academy of Sciences, in Leipzig. From 1969 until his retirement in 1974, Mühlenpfordt was director of the Forschungsbereiches Kern- und Isotopentechnik der Akademie.

Werner Hartmann was a German physicist who introduced microelectronics into East Germany. He studied physics at the Technische Hochschule Berlin and worked at Siemens before joining Fernseh GmbH. At the end of World War II, he and his research staff were flown to the Soviet Union to work on their atomic bomb project; he was assigned to Institute G. In 1955, he arrived in the German Democratic Republic (GDR); in the same year, he founded and became the director of the VEB Vakutronik Dresden, later VEB RFT Meßelektronik Dresden. In 1956, he completed his Habilitation at the Technische Hochschule Dresden and also became a professor for Kernphysikalische Elektronik there. In 1961, he founded the Arbeitsstelle für Molekularelektronik Dresden (AME). He was awarded the National Prize of GDR in 1958. In 1974, he was removed from his positions, significantly demoted, and sent to work as a staff scientist at the VEB Spurenmetalle Freiberg. Hartmann had been the object of security investigations by the Stasi for some time; while he was investigated at length and repeatedly interrogated, the alleged charges were politically motivated and no trial ever took place. The Werner-Hartmann-Preis für Chipdesign is an industrial award given in Hartmann's honor for achievement in the field of semiconductors.

Laboratory B, also known as Object B or Object 2011 during its period of operation, was a Soviet nuclear research site constructed in 1946 at Lake Sungulʹ in Chelyabinsk Oblast. It operated under the 9th Chief Directorate of the MVD and contributed to the Soviet nuclear weapons program and was responsible for the handling, treatment, and use of radioactive products generated in reactors, as well as radiation biology, dosimetry, and radiochemistry. It had two divisions: radiochemistry and radiobiophysics; the latter was headed by N. V. Timofeev-Resovskij.

Siegfried Flügge was a German theoretical physicist who made contributions to nuclear physics and the theoretical basis for nuclear weapons. He worked on the German nuclear energy project. From 1941 onward he was a lecturer at several German universities, and from 1956 to 1984, editor of the 54-volume, prestigious Handbuch der Physik.

Walter Herrmann was a German nuclear physicist and mechanical engineer who worked on the German nuclear energy project during World War II. After the war, he headed a laboratory for special issues of nuclear disintegration at Laboratory V in the Soviet Union.

Ernst Rexer was a German nuclear physicist. He worked on the German nuclear energy program during World War II. After the war, he was sent to Laboratory V, in Obninsk, to work on the Soviet atomic bomb project. In 1956, he was sent to East Germany, where he was a professor and director of the Institute for the Application of Radioactive Isotopes at the Technische Hochschule Dresden.

Josef 'Sepp' Schintlmeister was an Austrian-German nuclear physicist and alpinist from Radstadt. During World War II, he worked on the German nuclear energy project, also known as the Uranium Club. After World War II, he was sent Russia to work on the Soviet atomic bomb project. After he returned to Vienna, he took positions in East Germany. He was a professor of physics at the Technische Hochschule Dresden as well holding a leading scientific position at the Rossendorf Central Institute for Nuclear Research.