Demographic features of the population of Cambodia include population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations and other aspects of the population.

Montagnard is an umbrella term for the various indigenous peoples of the Central Highlands of Vietnam. The French term Montagnard ( ) signifies a mountain dweller, and is a carryover from the French colonial period in Vietnam. In Vietnamese, they are known by the term người Thượng, although this term can also be applied to other minority ethnic groups in Vietnam. In modern Vietnam, both terms are archaic, and indigenous ethnic groups are referred to as đồng bào or người dân tộc thiểu số. Earlier they were referred to pejoratively as the mọi. Sometimes the term Degar is used for the group as well. Most of those living in the United States refer to themselves as Montagnards, while those living in Vietnam refer to themselves by their individual ethnic group.

The post-Angkor period of Cambodia, also called the Middle Period, refers to the historical era from the early 15th century to 1863, the beginning of the French protectorate of Cambodia. As reliable sources are very rare, a defensible and conclusive explanation that relates to concrete events that manifest the decline of the Khmer Empire, recognised unanimously by the scientific community, has so far not been produced. However, most modern historians have approached a consensus in which several distinct and gradual changes of religious, dynastic, administrative and military nature, environmental problems and ecological imbalance coincided with shifts of power in Indochina and must all be taken into account to make an interpretation. In recent years scholars' focus has shifted increasingly towards human–environment interactions and the ecological consequences, including natural disasters, such as flooding and droughts.

Jarai people or Jarais are an Austronesian indigenous people and ethnic group native to Vietnam's Central Highlands, as well as in the Cambodian northeast Province of Ratanakiri. During the Vietnam War, many Jarai persons, as well as members of other Montagnard groups, worked with US Special Forces, and many were resettled with their families in the United States, particularly in North Carolina, after the war.

Zhou Daguan was a Chinese diplomat of the Yuan dynasty of China, serving under Temür Khan. He is most well known for his accounts of the customs of Cambodia and the Angkor temple complexes during his visit there. He arrived at Angkor in August 1296, and remained at the court of King Indravarman III until July 1297. He was neither the first nor the last Chinese representative to visit the Khmer Empire. However, his stay is notable because he later wrote a detailed report on life in Angkor, The Customs of Cambodia. His portrayal is today one of the most important sources of understanding of historical Angkor and the Khmer Empire. Alongside descriptions of several great Buddhist temples, such as the Bayon, the Baphuon, Angkor Wat, and others, the text also offers valuable information on the everyday life and the habits of the inhabitants of Angkor.

The largest of the ethnic groups in Cambodia are the Khmer, who comprise 95.8% of the total population and primarily inhabit the lowland Mekong subregion and the central plains. The Khmer historically have lived near the lower Mekong River in a contiguous arc that runs from the southern Khorat Plateau where modern-day Thailand, Laos and Cambodia meet in the northeast, stretching southwest through the lands surrounding Tonle Sap lake to the Cardamom Mountains, then continues back southeast to the mouth of the Mekong River in southeastern Vietnam.

Jarai is a Malayo-Polynesian language spoken by the Jarai people of Vietnam and Cambodia. The speakers of Jarai number approximately 530,000, not including other possible Jarai communities in countries other than Vietnam and Cambodia such as United States of America. They are the largest of the upland ethnic groups of Vietnam's Central Highlands known as Degar or Montagnards, and 25 per cent of the population in the Cambodian province of Ratanakiri.

The Bunong is an indigenous ethnic group in Cambodia. They are found primarily in Mondulkiri province in Cambodia. The Bunong is the largest indigenous highland ethnic group in Cambodia. They have their language called Bunong, which belongs to Bahnaric branch of Austroasiatic languages. The majority of Bunong people are animists, but a minority of them follows Christianity and Theravada Buddhism. After Cambodia's independence in 1953, Prince Sihanouk created a novel terminology, referring to the country's highland inhabitants, including the Bunong, as Khmer Loeu. Under the People's Republic of Kampuchea (1979-89), the generic term ជនជាតិភាគតិច "ethnic minorities" came to be in use and the Bunong became referred to as ជនជាតិព្នង meaning "ethnic Pnong". Today, the generic term that many Bunong use to refer to themselves is ជនជាតិដើមភាគតិច, which can be translated as "indigenous minority" and involves special rights, notably to collective land titles as an "indigenous community". In Vietnam, Bunong-speaking peoples are recurrently referred to as Mnong.

The United Front for the Liberation of Oppressed Races was an organization whose objective was autonomy for various indigenous peoples and ethnic minorities in South Vietnam, including the Montagnards in the Central Highlands, the Chams in Central Vietnam, and the Khmer Krom in Southern Vietnam. Initially a political movement, after 1969 it evolved into a fragmented guerrilla group that carried on simultaneous insurgencies against the governments of South Vietnam under President Nguyen Van Thieu and North Vietnam of Ho Chi Minh. Opposed to all forms of Vietnamese rule, FULRO fought against both sides in the Vietnam War against the Soviet-aligned North and the American-aligned South at the same time. FULRO's primary supporter during the 1960s and early 1970s conflict in Southeast Asia was Cambodia, with some aid sent by the People's Republic of China during the period of the Third Indochina War.

The k'ni, also known as mim or memm in Cambodia, popularly known as a mouth violin is a mouth resonator fiddle, i.e. a fiddle-like instrument used by the Jarai people in Vietnam and Tampuan people in Cambodia.

Racism in Vietnam has been mainly directed by the majority and dominant ethnic Vietnamese Kinh against ethnic minorities such as Degars (Montagnards), Chams and the Khmer Krom. It has also been directed against black people from other countries around the world as well.

George Groslier was a French polymath who – through his work as a painter, writer, historian, archaeologist, ethnologist, architect, photographer and curator – studied, described, popularized and worked to preserve the arts, culture and history of the Khmer Empire of Cambodia. Born in Phnom Penh to a French civil servant – he was the first French child ever born in Cambodia – Groslier was taken by his mother to France at the age of two and grew up in Marseille. Aspiring to become a painter, he tried but failed to win the prestigious Prix de Rome. Shortly afterwards, he returned to Cambodia, on a mission from the Ministry of Education. There he met and befriended a number of French scholars of traditional Cambodian culture. Under their influence, he wrote and published, in France in 1913, his initial book on this subject: Danseuses Cambodgiennes – Anciennes et Modernes. It was the very first scholarly work ever published in any language on Cambodian dance. He then returned to Cambodia, traveling the length and breadth of the country to examine its ancient monuments and architecture. From this experience came his book A l'ombre d 'Angkor; notes et impressions sur les temples inconnus de l'ancien Cambodge. In June 1914, Groslier enlisted in the French army and was employed as a balloonist in the early part of World War I. It was during this time that he met and married sportswoman Suzanne Cecile Poujade; they eventually had three children.

The United Front for the Liberation of Oppressed Races waged a nearly three decade long insurgency against the governments of North and South Vietnam, and later the unified Socialist Republic of Vietnam. The FULRO insurgents represented the interests of indigenous Muslim and Hindu Cham, Montagnards, and Buddhist Khmer Krom against the ethnic Kinh Vietnamese. They were supported and equipped by China and Cambodia according to those countries' interests in the Indochina Wars.

Vietnamization or Vietnamisation is the acquisition or imposition of elements of Vietnamese culture, in particular the Vietnamese language and customs. This was experienced in some historic periods by the non-Vietnamese populations of territories controlled or substantially under the influence of Vietnam. As with other examples of cultural assimilation, it could either be voluntary or forced and is most visible in the case of territories where the Vietnamese language or culture were dominant or where their adoption could result in increased prestige or social status, as was the case of the nobility of Champa, or other minorities like Tai, Chinese, and Khmers. To a certain extent Vietnamization was also administratively promoted by the authorities regardless of eras.

Khmer–Cham wars were a series of conflicts and contests between states of the Khmer Empire and Champa, later involving Đại Việt, that lasted from the mid-10th century to the early 13th century in mainland Southeast Asia. The first conflict began in 950 AD when Khmer troops sacked the Cham principality of Kauthara. Tensions between the Khmer Empire and Champa reached a climax in the middle of the 12th century when both deployed field armies and waged devastating wars against each other. The conflicts ended after the Khmer army voluntarily retreated from occupying Champa in 1220.

The Montagnard country of South Indochina, sometimes abbreviated as PMSI, was an autonomous territory of French Indochina, and an autonomous federation within the French Union, created in 1946 following the French reconquest of the Cao nguyên Trung bộ from the Democratic Republic of Vietnam during the First Indochina War. The territory was supposed to be an autonomous homeland of the Montagnard people within French Indochina, but existed mainly to serve French colonial interests in the region.

Wat Vihear Suor is a Theravada Buddhist temple located in Kandal Province, Cambodia. It was built on an older pre-Buddhist cult site belonging to the Angkor era.

Sra peang is a rice wine stored in earthen pots and indigenous to several ethnic groups in Cambodia, in areas such as Mondulkiri or Ratanakiri. It is made of fermented glutinous rice mixed with several kinds of local herbs. The types and amount of herbs added differ according to ethnic group and region. This mixture is then put into a large earthenware jug, covered, and allowed to ferment for at least one month. The strength of this alcoholic beverage is typically 15 to 25 percent alcohol by volume.

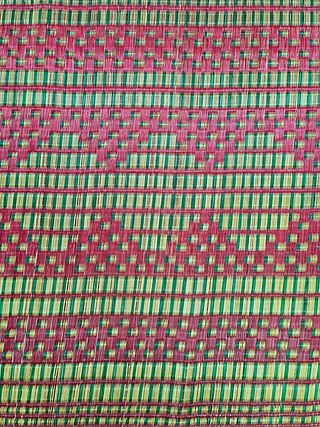

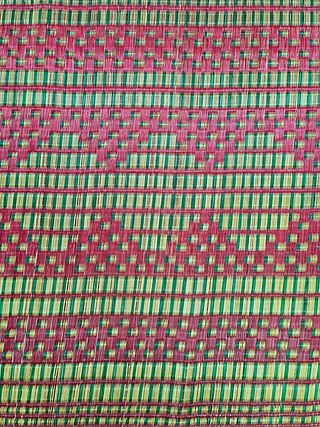

A Cambodian mat also known as a kantael is a woven mat made from palm or reed in Cambodia. The Cambodian mat consists of an ordinary mat, below which are fixed pads of strongly packed cotton, with the help of a special loom. They are specific to the Khmer people.

A ballista elephant, also known as a Khmer ballista, is a war elephant mounted with a simple or double-bowed ballista which was used by the Angkorian civilization. They are considered as the summit of sophistication of Khmer weaponry comparable to the carrobalista in the legion of Vegetius.