The 17th century BC was the century that lasted from 1700 BC to 1601 BC.

Mount Vesuvius is a somma-stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples in Campania, Italy, about 9 km (5.6 mi) east of Naples and a short distance from the shore. It is one of several volcanoes forming the Campanian volcanic arc. Vesuvius consists of a large cone partially encircled by the steep rim of a summit caldera, resulting from the collapse of an earlier, much higher structure.

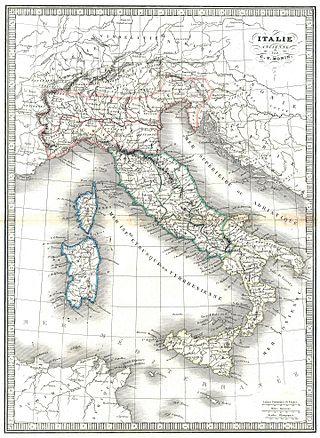

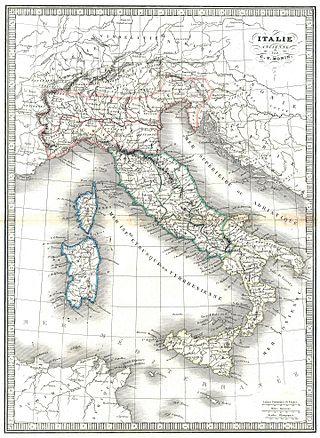

Lipari is a comune including six of seven islands of the Aeolian Islands and it is located in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the northern coast of Sicily, southern Italy; it is administratively part of the Metropolitan City of Messina. Its population is 12,821, but during the May to September tourist season, the total population may reach up to 20,000. It is also the name of the biggest island in the archipelago, where the main urban area of the comune is located.

Vitrification is the full or partial transformation of a substance into a glass, that is to say, a non-crystalline amorphous solid. Glasses differ from liquids structurally and glasses possess a higher degree of connectivity with the same Hausdorff dimensionality of bonds as crystals: dimH = 3. In the production of ceramics, vitrification is responsible for their impermeability to water.

The volcanism of Italy is due chiefly to the presence, a short distance to the south, of the boundary between the Eurasian Plate and the African Plate. Italy is a volcanically active country, containing the only active volcanoes in mainland Europe. The lava erupted by Italy's volcanoes is thought to result from the subduction and melting of one plate below another.

The Apennine culture is a technology complex in central and southern Italy from the Italian Middle Bronze Age. In the mid-20th century the Apennine was divided into Proto-, Early, Middle and Late sub- phases, but now archaeologists prefer to consider as "Apennine" only the ornamental pottery style of the later phase of Middle Bronze Age (BM3). This phase is preceded by the Grotta Nuova facies and by the Protoapennine B facies and succeeded by the Subapennine facies of 13th-century. Apennine pottery is a burnished ware incised with spirals, meanders and geometrical zones, filled with dots or transverse dashes. It has been found on Ischia island in association with LHII and LHIII pottery and on Lipari in association with LHIIIA pottery, which associations date it to the Late Bronze Age as it is defined in Greece and the Aegean.

The Phlegraean Fields is a large volcanic caldera situated to the west of Naples, Italy. It is part of the Campanian volcanic arc, which includes Mount Vesuvius on the east side of Naples. The Phlegraean Fields is monitored by the Vesuvius Observatory. It was declared a regional park in 2003.

Avellino is a town and comune, capital of the province of Avellino in the Campania region of southern Italy. It is situated in a plain surrounded by mountains 47 kilometres (29 mi) east of Naples and is an important hub on the road from Salerno to Benevento.

The Minoan eruption was a catastrophic volcanic eruption that devastated the Aegean island of Thera circa 1600 BCE. It destroyed the Minoan settlement at Akrotiri, as well as communities and agricultural areas on nearby islands and the coast of Crete with subsequent earthquakes and paleotsunamis. With a Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) of between 6 and 7, it resulted in the ejection of approximately 28–41 km3 (6.7–9.8 cu mi) of dense-rock equivalent (DRE), the eruption was one of the largest volcanic events in human history. Since tephra from the Minoan eruption serves as a marker horizon in nearly all archaeological sites in the Eastern Mediterranean, its precise date is of high importance and has been fiercely debated among archaeologists and volcanologists for decades, without coming to a definite conclusion.

Gyali is a Greek volcanic island in the Dodecanese, located halfway between the south coast of Kos (Kardamaina) and Nisyros. It consists of rhyolitic obsidian lava domes and pumice deposits. No historical eruptions are known, but the most recent pumice eruptions overlie soils containing pottery and obsidian artifacts from the Neolithic period. The island has two distinct segments, with the northeastern part almost entirely made of obsidian and the southwestern part of pumice. These are connected by a narrow isthmus and beach made of modern reef sediments. Anciently, the island was known as Istros.

Dense-rock equivalent (DRE) is a volcanologic calculation used to estimate volcanic eruption volume. One of the widely accepted measures of the size of a historic or prehistoric eruption is the volume of magma ejected as pumice and volcanic ash, known as tephra during an explosive phase of the eruption, or the volume of lava extruded during an effusive phase of a volcanic eruption. Eruption volumes are commonly expressed in cubic kilometers (km3).

The prehistory of Italy began in the Paleolithic period, when species of Homo colonized the Italian territory for the first time, and ended in the Iron Age, when the first written records appeared in Italy.

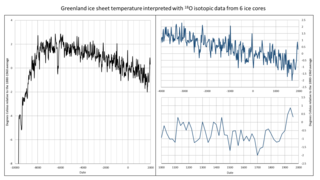

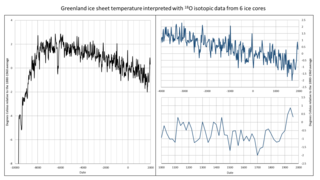

The Middle Bronze Age Cold Epoch was a period of unusually cold climate in the North Atlantic region that lasted about from 1800 BC to 1500 BC. It was followed by the Bronze Age Optimum.

Pompeii was an ancient city located in what is now the comune of Pompei near Naples in the Campania region of Italy. Pompeii, along with Herculaneum and many villas in the surrounding area, was buried under 4 to 6 m of volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Herculaneum was an ancient Roman town, located in the modern-day comune of Ercolano, Campania, Italy. Herculaneum was buried under volcanic ash and pumice in the Eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Nola is a town and a municipality in the Metropolitan City of Naples, Campania, southern Italy. It lies on the plain between Mount Vesuvius and the Apennines. It is traditionally credited as the diocese that introduced bells to Christian worship.

Of the many eruptions of Mount Vesuvius, a major stratovolcano in southern Italy, the best-known is its eruption in 79 AD, which was one of the deadliest.

Mount Barbaro or Mount Gauro in Italy Monte Barbaro or Monte Gauro, is one of the eruptive vents of the Phlegraean Fields, a volcanic field of Italy located in Campania.

The Campanian Ignimbrite eruption was a major volcanic eruption in the Mediterranean during the late Quaternary, classified 7 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI). The event has been attributed to the Archiflegreo volcano, the 12-by-15-kilometre-wide caldera of the Phlegraean Fields, located 20 km (12 mi) west of Mount Vesuvius under the western outskirts of the city of Naples and the Gulf of Pozzuoli, Italy. Estimates of the date and magnitude of the eruption(s), and the amount of ejected material have varied considerably during several centuries the site has been studied. This applies to most significant volcanic events that originated in the Campanian Plain, as it is one of the most complex volcanic structures in the world. However, continued research, advancing methods, and accumulation of volcanological, geochronological, and geochemical data have improved the dates' accuracy.

Kurile Lake is a caldera and crater lake in Kamchatka, Russia. It is also known as Kurilskoye Lake or Kuril Lake. It is part of the Eastern Volcanic Zone of Kamchatka which, together with the Sredinny Range, forms one of the volcanic belts of Kamchatka. These volcanoes form from the subduction of the Pacific Plate beneath the Okhotsk Plate and the Asian Plate.