The history of Sumer spans the 5th to 3rd millennia BCE in southern Mesopotamia, and is taken to include the prehistoric Ubaid and Uruk periods. Sumer was the region's earliest known civilization and ended with the downfall of the Third Dynasty of Ur around 2004 BCE. It was followed by a transitional period of Amorite states before the rise of Babylonia in the 18th century BCE.

Lagash was an ancient city state located northwest of the junction of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers and east of Uruk, about 22 kilometres (14 mi) east of the modern town of Al-Shatrah, Iraq. Lagash was one of the oldest cities of the Ancient Near East. The ancient site of Nina is around 10 km (6.2 mi) away and marks the southern limit of the state. Nearby Girsu, about 25 km (16 mi) northwest of Lagash, was the religious center of the Lagash state. The Lagash state's main temple was the E-ninnu at Girsu, dedicated to the god Ningirsu. The Lagash state incorporated the ancient cities of Lagash, Girsu, Nina.

Uru-ka-gina, Uru-inim-gina, or Iri-ka-gina was King of the city-states of Lagash and Girsu in Mesopotamia, and the last ruler of the 1st Dynasty of Lagash. He assumed the title of king, claiming to have been divinely appointed, upon the downfall of his corrupt predecessor, Lugalanda.

The Third Dynasty of Ur, also called the Neo-Sumerian Empire, refers to a 22nd to 21st century BC Sumerian ruling dynasty based in the city of Ur and a short-lived territorial-political state which some historians consider to have been a nascent empire.

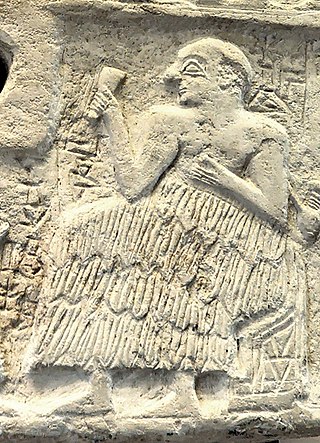

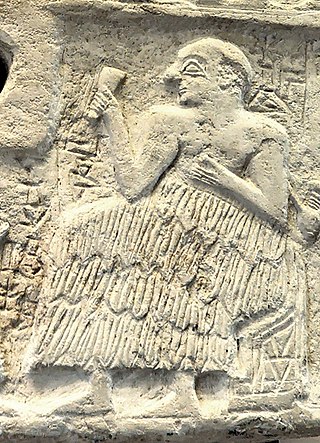

Ur-Nanshe also Ur-Nina, was the first king of the First Dynasty of Lagash in the Sumerian Early Dynastic Period III. He is known through inscriptions to have commissioned many buildings projects, including canals and temples, in the state of Lagash, and defending Lagash from its rival state Umma. He was probably not from royal lineage, being the son of Gunidu who was recorded without an accompanying royal title. He was the father of Akurgal, who succeeded him, and grandfather of Eanatum. Eanatum expanded the kingdom of Lagash by defeating Umma as illustrated in the Stele of the Vultures and continue building and renovation of Ur-Nanshe's original buildings.

Ibbi-Sin, son of Shu-Sin, was king of Sumer and Akkad and last king of the Ur III dynasty, and reigned c. 2028–2004 BCE or possibly c. 1964–1940 BCE. During his reign, the Sumerian empire was attacked repeatedly by Amorites. As faith in Ibbi-Sin's leadership failed, Elam declared its independence and began to raid as well.

The Dynasty of Isin refers to the final ruling dynasty listed on the Sumerian King List (SKL). The list of the Kings Isin with the length of their reigns, also appears on a cuneiform document listing the kings of Ur and Isin, the List of Reigns of Kings of Ur and Isin.

The Early Dynastic period is an archaeological culture in Mesopotamia that is generally dated to c. 2900 – c. 2350 BC and was preceded by the Uruk and Jemdet Nasr periods. It saw the development of writing and the formation of the first cities and states. The ED itself was characterized by the existence of multiple city-states: small states with a relatively simple structure that developed and solidified over time. This development ultimately led to the unification of much of Mesopotamia under the rule of Sargon, the first monarch of the Akkadian Empire. Despite this political fragmentation, the ED city-states shared a relatively homogeneous material culture. Sumerian cities such as Uruk, Ur, Lagash, Umma, and Nippur located in Lower Mesopotamia were very powerful and influential. To the north and west stretched states centered on cities such as Kish, Mari, Nagar, and Ebla.

Shara was a Mesopotamian god associated with the city of Umma and other nearby settlements. He was chiefly regarded as the tutelary deity of this area, responsible for agriculture, animal husbandry and irrigation, but he could also be characterized as a divine warrior. In the third millennium BCE his wife was Ninura, associated with the same area, but later, in the Old Babylonian period, her cult faded into obscurity and Shara was instead associated with Usaḫara or Kumulmul. An association between him and Inanna is well attested. In Umma, he was regarded as the son of Inanna of Zabalam and an unknown father, while in the myth Inanna's Descent to the Underworld he is one of the servants mourning her temporary death. He also appears in the myth of Anzû, in which he is one of the three gods who refuse to fight the eponymous monster.

Kazalla or Kazallu (Ka-zal-luki) is the name given in Akkadian sources to a city in the ancient Near East whose locations is unknown. Its god is Numushda with his consort Namrat. There are indications that the god Lugal-awak also lived in Kazallu.

Geshtinanna was a Mesopotamian goddess best known due to her role in myths about the death of Dumuzi, her brother. It is not certain what functions she fulfilled in the Mesopotamian pantheon, though her association with the scribal arts and dream interpretation is well attested. She could serve as a scribe in the underworld, where according to the myth Inanna's Descent she had to reside for a half of each year in place of her brother.

Ishbi-Erra was the founder of the dynasty of Isin, reigning from c. 2017 — c. 1986 BC on the middle chronology or 1953 BC — c. 1920 BC on the short chronology. Ishbi-Erra was preceded by Ibbi-Sin of the third dynasty of Ur in ancient Lower Mesopotamia, and then succeeded by Šu-ilišu. According to the Weld-Blundell Prism, Išbi-erra reigned for 33 years and this is corroborated by the number of his extant year-names. While in many ways this dynasty emulated that of the preceding one, its language was Akkadian as the Sumerian language had become moribund in the latter stages of the third dynasty of Ur.

Akurgal was the second king (Ensi) of the first dynasty of Lagash. His relatively short reign took place in the first part of the 25th century BCE, during the period of the archaic dynasties. He succeeded his father, Ur-Nanshe, founder of the dynasty, and was replaced by his son Eannatum.

Il was king of the Sumerian city-state of Umma, circa 2400 BCE. His father was Eandamu, and his grandfather was King Enakalle, who had been vanquished by Eannatum of Lagash. Il was successor to Ur-Lumma. According to an inscription, before becoming king, he had been temple administrator in Zabalam: "At this time, Il, who was the temple administrator of Zabalam, marched in retreat from Girsu to Umma and took the governorship of Umma for himself." He ruled for at least 14 years.

Ur-Lumma was a ruler of the Sumerian city-state of Umma, circa 2400 BCE. His father was King Enakalle, who had been vanquished by Eannatum of Lagash. Ur-Lumma claimed the title of "King" (Lugal). His reign lasted at least 12 years.

Lugalshaengur, , was ensi (governor) of the Sumerian city-state of Lagash.

Puzrish-Dagan is an important archaeological site in Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate (Iraq). It is best-known for the thousands of clay tablets that are known to have come from the site through looting during the early twentieth century.

Ḫabūrītum (dḫa-bu-ri-tum) was a goddess of the river Khabur worshiped in ancient Syria. She was incorporated into the Mesopotamian pantheon in the Ur III period. Her original cult center was most likely Sikani, which in the early third millennium was located in an area ruled by Hurrians. Not much is known about her character. In Mesopotamian texts she appears chiefly in association with other deities worshiped in Syria, such as Dagan and Ishara.

Belet-Šuḫnir and Belet-Terraban were a pair of Mesopotamian goddesses best known from the archives of the Third Dynasty of Ur, but presumed to originate further north, possibility in the proximity of modern Kirkuk and ancient Eshnunna. Their names are usually assumed to be derived from cities where they were originally worshiped. Both in ancient sources, such as ritual texts, seal inscriptions and god lists, and in modern scholarship, they are typically treated as a pair. In addition to Ur and Eshnunna, both of them are also attested in texts from Susa in Elam. Their character remains poorly understood due to scarcity of sources, though it has been noted that the tone of many festivals dedicated to them was "lugubrious," which might point at an association with the underworld.

Igalim or Igalimma was a Mesopotamian god from the local pantheon of the state of Lagash. He was closely associated with Ningirsu, possibly originating as the personification of the door of his temple, and was regarded as a member of his family. His older brother was Shulshaga and his mother was Bau, as already attested in Early Dynastic sources. Until the end of the Ur III period he was worshiped in Lagash and Girsu, where he had a temple, though he also appears in a number of later texts.