Yamata no Orochi, or simply Orochi (大蛇), is a legendary eight-headed and eight-tailed Japanese dragon/serpent.

Strigoi in Romanian mythology are troubled spirits that are said to have risen from the grave. They are attributed with the abilities to transform into an animal, become invisible, and to gain vitality from the blood of their victims. Bram Stoker's Dracula may be modern interpretation of the Strigoi through their historic links with vampirism.

Ileana Cosânzeana is a figure in Romanian mythology. She is represented as a beautiful and good-natured princess or daughter of an Emperor, or described as a fairy with immense powers.

The Zmeu is a fantastic creature of Romanian folklore and Romanian mythology.

Princess and dragon is an archetypical premise common to many legends, fairy tales, and chivalric romances. Northrop Frye identified it as a central form of the quest romance.

The Dacian draco was a military standard used by troops of the ancient Dacian people, which can be seen in the hands of the soldiers of Decebalus in several scenes depicted on Trajan's Column in Rome, Italy. This wind instrument has the form of a dragon with open wolf-like jaws containing several metal tongues. The hollow dragon's head was mounted on a pole with a fabric tube affixed at the rear. In use, the draco was held up into the wind, or above the head of a horseman, where it filled with air and gave the impression it was alive while making a shrill sound as the wind passed through its strips of material. The Dacian draco likely influenced the development of the similar Roman draco.

A Slavic dragon is any dragon in Slavic mythology, including the Russian zmei, Ukrainian zmiy, and its counterparts in other Slavic cultures: the Bulgarian zmey, the Slovak drak and šarkan, Czech drak, Polish żmij, the Serbo-Croatian zmaj, the Macedonian zmej (змеј) and the Slovene zmaj. The Romanian zmeu could also be deemed a "Slavic" dragon, but a non-cognate etymology has been proposed.

The Scholomance was a fabled school of black magic in Romania, especially in the region of Transylvania. It was run by the Devil, according to folkloric accounts. The school enrolled about ten students to become the Solomonari. Courses taught included the speech of animals and magic spells. One of the graduates was chosen by the Devil to be the Weathermaker and tasked with riding a dragon to control the weather.

Corvin Castle, also known as Hunyadi Castle or Hunedoara Castle, is a Gothic-Renaissance castle in Hunedoara, Romania. It is considered one of the largest castles in Europe and is featured as one of the Seven Wonders of Romania.

Greuceanu is a hero of the Romanian folklore. It is a brave young man who finds that the Sun and the Moon have been stolen by zmei. After a long fight with the three zmei and their wives (zmeoaice), Greuceanu sets the Sun and the Moon free so the people on Earth have light again.

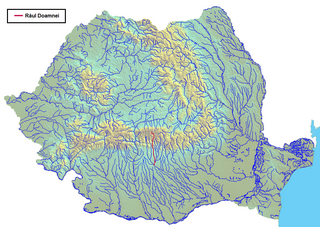

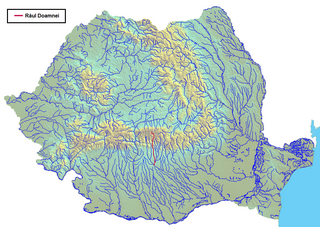

Râul Doamnei is a left tributary of the river Argeș in Romania. Its source is on the eastern slope of Moldoveanu Peak, the highest mountain peak in Romania. It discharges into the Argeș just north of Pitești. Its upper course, upstream from the confluence with the Zârna, is also called Valea Rea. Its length is 107 km (66 mi) and its basin size is 1,836 km2 (709 sq mi). It frequently dries up in summer, owing to the works upstream that have redirected part of its water supply toward a reservoir serving the hydroelectric plant on the Argeș.

The Solomonar or Șolomonar is a wizard believed in Romanian folklore to ride a dragon and control the weather, causing rain, thunder, or hailstorm.

Făt-Frumos with the Golden Hair or The Foundling Prince is a Romanian fairy tale collected by Petre Ispirescu in Legende sau basmele românilor.

A zduhać and vetrovnjak in Serbian tradition, and a dragon man in Bulgarian, Macedonian and southern Serbian traditions, were men believed to have an inborn supernatural ability to protect their estate, village, or region against destructive weather conditions, such as storms, hail, or torrential rains. It was believed that the souls of these men could leave their bodies in sleep, to intercept and fight with demonic beings imagined as bringers of bad weather. Having defeated the demons and taken away the stormy clouds they brought, the protectors would return into their bodies and wake up tired.

An ala or hala is a female mythological creature recorded in the folklore of Bulgarians, Macedonians, and Serbs. Ale are considered demons of bad weather whose main purpose is to lead hail-producing thunderclouds in the direction of fields, vineyards, or orchards to destroy the crops, or loot and take them away. Extremely voracious, ale particularly like to eat children, though their gluttony is not limited to Earth. It is believed they sometimes try devouring the Sun or the Moon, causing eclipses, and that it would mean the end of the world should they succeed. When people encounter an ala, their mental or physical health, or even life, are in peril; however, her favor can be gained by approaching her with respect and trust. Being in a good relationship with an ala is very beneficial, because she makes her favorites rich and saves their lives in times of trouble.

The folklore of Romania is the collection of traditions of the Romanians. A feature of Romanian culture is the special relationship between folklore and the learned culture, determined by two factors. First, the rural character of the Romanian communities resulted in an exceptionally vital and creative traditional culture. Folk creations were the main literary genre until the 18th century. They were both a source of inspiration for cultivated creators and a structural model. Second, for a long time learned culture was governed by official and social commands and developed around courts of princes and boyars, as well as in monas

Lazăr Șăineanu was a United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia-born philologist, linguist, folklorist and cultural historian. A specialist in Oriental and Romance studies, as well as a Germanist, he was primarily known for his contribution to Yiddish and Romanian philology, his work in evolutionary linguistics, and his activity as a literary and philological comparatist. Șăineanu also had innovative contributions to the investigation and anthologizing of Romanian folklore, placed in relation to Balkan and East Central European traditions, as well as to the historical evolution of Romanian in a larger Balkan context, and was a celebrated early contributor to Romanian lexicography. His main initiatives in these fields are a large corpus of collected fairy tales and the 1896 Dicționarul universal al limbii române, which have endured among the most popular Romanian scientific works.

Trandafiru is a Romanian fairy tale collected by Arthur Carl Victor Schott and Albert Schott in the mid-19th century and sourced from Banat.