Wilkes-Barre is a city in and the county seat of Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, United States. Located at the center of the Wyoming Valley in Northeastern Pennsylvania, it had a population of 44,328 in the 2020 census. It is the second-largest city, after Scranton, in the Scranton–Wilkes-Barre–Hazleton, PA Metropolitan Statistical Area, which had a population of 567,559 as of the 2020 census, making it the fifth-largest metropolitan area in Pennsylvania after the Delaware Valley, Greater Pittsburgh, the Lehigh Valley, and Greater Harrisburg.

Luzerne County is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. According to the United States Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 906 square miles (2,350 km2), of which 890 square miles (2,300 km2) is land and 16 square miles (41 km2) is water. It is Northeastern Pennsylvania's second-largest county by total area. As of the 2020 census, the population was 325,594, making it the most populous county in the northeastern part of the state. The county seat and most populous city is Wilkes-Barre. Other populous communities include Hazleton, Kingston, Nanticoke, and Pittston. Luzerne County is included in the Scranton–Wilkes-Barre–Hazleton Metropolitan Statistical Area, which has a total population of 555,426 as of 2017. The county is part of the Northeast Pennsylvania region of the state.

Scranton is a city in and the county seat of Lackawanna County, Pennsylvania, United States. With a population of 76,328 as of the 2020 U.S. census, Scranton is the most populous city in Northeastern Pennsylvania and the Wyoming Valley metropolitan area, which has a population of 562,037 as of 2020. It is the sixth-most populous city in Pennsylvania.

A mining accident is an accident that occurs during the process of mining minerals or metals. Thousands of miners die from mining accidents each year, especially from underground coal mining, although accidents also occur in hard rock mining. Coal mining is considered much more hazardous than hard rock mining due to flat-lying rock strata, generally incompetent rock, the presence of methane gas, and coal dust. Most of the deaths these days occur in developing countries, and rural parts of developed countries where safety measures are not practiced as fully. A mining disaster is an incident where there are five or more fatalities.

Mine rescue or mines rescue is the specialised job of rescuing miners and others who have become trapped or injured in underground mines because of mining accidents, roof falls or floods and disasters such as explosions.

On March 25, 1947, the Centralia No. 5 coal mine exploded near the town of Centralia, Illinois, killing 111 people. The Mine Safety and Health Administration of the United States Department of Labor reported the explosion was caused when an underburdened shot or blown-out shot ignited coal dust. The US Department of Labor lists the disaster as the second worst US mining disaster since 1940 with a total of 111 men dead.

The Ulyanovskaya Mine disaster was caused by a methane explosion that occurred on March 19, 2007 in the Ulyanovskaya longwall coal mine in the Kemerovo Oblast. At least 108 people were reported to have been killed by the blast, which occurred at a depth of about 270 meters (885 feet) at 10:19 local time. The mine disaster was Russia's deadliest in more than a decade.

The 2007 Zasyadko mine disaster was a mining accident that happened on November 18, 2007 at the Zasyadko coal mine in the eastern Ukrainian city of Donetsk.

The Minnie Pit disaster was a coal mining accident that took place on 12 January 1918 in Halmer End, Staffordshire, in which 155 men and boys died. The disaster, which was caused by an explosion due to firedamp, is the worst ever recorded in the North Staffordshire Coalfield. An official investigation never established what caused the ignition of flammable gases in the pit.

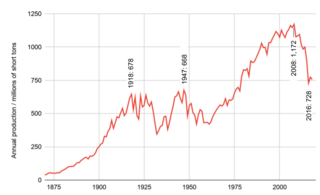

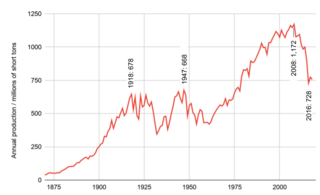

The history of coal mining in the United States starts with the first commercial use in 1701, within the Manakin-Sabot area of Richmond, Virginia. Coal was the dominant power source in the late 1800s and early 1900s, and although in rapid decline it remains a significant source of energy in 2023.

The Twin Shaft disaster occurred in the Newton Coal Company's Twin Shaft Colliery in Pittston, Pennsylvania, United States, on June 28, 1896, when a massive cave-in killed fifty-eight miners.

The 2009 Handlová mine blast occurred on 10 August 2009 roughly 330 metres (1,080 ft) underground in Trencin Region, Slovakia at Hornonitrianske Bane Prievidza, a.s.s (HNB) coal mine located in the town of Handlová. 20 people were killed, nine others suffered minor injuries and were taken to hospital for treatment. Some historians have called the disaster the largest mining tragedy in Slovakia’s history. The deadly explosion, probably caused by flammable gases, occurred after mine rescuers had earlier been deployed to extinguish a fire in the Eastern shaft of the mine.

The Avondale Colliery was a coal mine in Plymouth Township, Luzerne County, near Plymouth, Pennsylvania in the small town of Avondale. The mine was considered to be "one of the best and worst" operating in Pennsylvania's Wyoming Valley.

The Avondale Mine disaster was a massive fire at the Avondale Colliery near Plymouth Township, Pennsylvania, on September 6, 1869. It caused the death of 110 workers. It started when the wooden lining of the mine shaft caught fire and ignited the coal breaker built directly overhead. The shaft was the only entrance and exit to the mine, and the fire trapped and suffocated 108 of the workers. It was the greatest mine disaster to that point in American history.

Energy resources bring with them great social and economic promise, providing financial growth for communities and energy services for local economies. However, the infrastructure which delivers energy services can break down in an energy accident, sometimes causing considerable damage. Energy fatalities can occur, and with many systems deaths will happen often, even when the systems are working as intended.

Mine safety is a broad term referring to the practice of controlling and managing a wide range of hazards associated with the life cycle of mining-related activities. Mine safety practice involves the implementation of recognised hazard controls and/or reduction of risks associated with mining activities to legally, socially and morally acceptable levels. While the fundamental principle of mine safety is to remove health and safety risks to mine workers, mining safety practice may also focus on the reduction of risks to plant (machinery) together with the structure and orebody of the mine.

In February 2016, a series of explosions caused the deaths of 36 people, including 31 miners and five rescue workers, at the Severnaya coal mine 10 kilometres north of the city of Vorkuta, Komi Republic, Russia. The explosions were believed to be caused by ignition of leaking methane gas. It is the second deadliest mining disaster of the 2010s behind the Soma mine disaster, and fourth deadliest of the 21st century thus far.

Plymouth, Pennsylvania sits on the west side of Pennsylvania's Wyoming Valley, wedged between the Susquehanna River and the Shawnee Mountain range. Just below the mountain are hills that surround the town and form a natural amphitheater that separates the town from the rest of the valley. Below the hills, the flat lands are formed in the shape of a frying pan, the pan being the Shawnee flats, once the center of the town's agricultural activities, and the handle being a spit of narrow land extending east from the flats, where the center of town is located. At the beginning of the 19th century, Plymouth's primary industry was agriculture. However, vast anthracite coal beds lay below the surface at various depths, and by the 1850s, coal mining had become the town's primary occupation.