Basque is the only surviving Paleo-European language spoken in Europe, predating the arrival of speakers of the Indo-European languages that dominate the continent today. Basque is spoken by the Basques and other residents of the Basque Country, a region that straddles the westernmost Pyrenees in adjacent parts of northern Spain and southwestern France. Basque is classified as a language isolate, with no relationship to any other language having been established. The Basques are indigenous to and primarily inhabit the Basque Country. The Basque language is spoken by 806,000 Basques in all territories. Of these, 93.7% (756,000) are in the Spanish area of the Basque Country and the remaining 6.3% (50,000) are in the French portion.

The Basques are a Southwestern European ethnic group, characterised by the Basque language, a common culture and shared genetic ancestry to the ancient Vascones and Aquitanians. Basques are indigenous to, and primarily inhabit, an area traditionally known as the Basque Country —a region that is located around the western end of the Pyrenees on the coast of the Bay of Biscay and straddles parts of north-central Spain and south-western France.

Basque nationalism is a form of nationalism that asserts that Basques, an ethnic group indigenous to the western Pyrenees, are a nation and promotes the political unity of the Basques, today scattered between Spain and France. Since its inception in the late 19th century, Basque nationalism has included Basque independence movements.

The Basque Nationalist Party, officially Basque National Party in English, is a Basque nationalist and regionalist political party. The party is located in the centre of the political spectrum.

Sabino Policarpo Arana Goiri, Sabin Polikarpo Arana Goiri, or Arana ta Goiri'taŕ Sabin (self-styled), was a Spanish writer and the founder of the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV). Arana is considered the father of Basque nationalism.

The President of the Basque Government, usually known in the Basque language as the Lehendakari, is the head of government of the Basque Autonomous Community. The lehendakari leads the executive branch of the regional government.

Spanish names are the traditional way of identifying, and the official way of registering, a person in Spain. They are composed of a given name and two surnames. Traditionally, the first surname is the father's first surname, and the second is the mother's first surname. Since 1999, the order of the surnames in a family in Spain is decided when registering the first child, but the traditional order is nearly universally chosen.

The Basque Country is the name given to the home of the Basque people. The Basque Country is located in the western Pyrenees, straddling the border between France and Spain on the coast of the Bay of Biscay.

The Kingdom of Navarre, originally the Kingdom of Pamplona, was a Basque kingdom that occupied lands on both sides of the western Pyrenees, with its northernmost areas originally reaching the Atlantic Ocean, between present-day Spain and France.

Fuero, Fur, Foro or Foru is a Spanish legal term and concept. The word comes from Latin forum, an open space used as a market, tribunal and meeting place. The same Latin root is the origin of the French terms for and foire, and the Portuguese terms foro and foral; all of these words have related, but somewhat different meanings.

The lauburu is an ancient hooked cross with four comma-shaped heads and the most widely known traditional symbol of the Basque Country and the Basque people. In the past, it has also been associated with the Galicians, Illyrians and Asturians.

Etxeberria (Basque pronunciation:[etʃeβeri.a], modern Basque spelling) is a Basque language placename and surname from the Basque Country in Spain and France, meaning 'the new house'. It shows one meaningful variant, Etxeberri (no Basque article –a, 'the'), and a number of later spelling variants produced in Spanish and other languages. Etxebarri(a) is a western Basque dialectal variant, with the same etymology. Etxarri (Echarri) is attested as stemming from Etxaberri.

The Southern Basque Country refers to the Basque territories within Spain as a unified whole.

Inigo derives from the Castilian rendering (Íñigo) of the medieval Basque name Eneko. Ultimately, the name means "my little (love)". While mostly seen among the Iberian diaspora, it also gained a limited popularity in the United Kingdom.

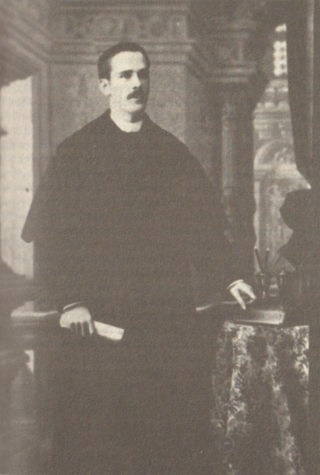

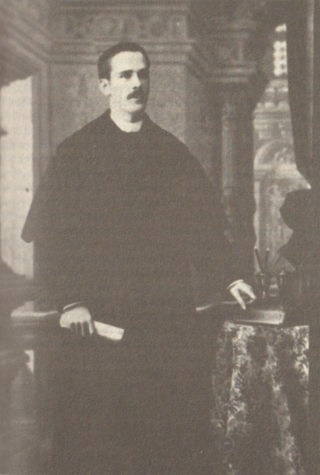

Resurrección María de Azkue was an influential Basque priest, musician, poet, writer, sailor and academic. He made several major contributions to the study of the Basque language and was the first head of the Euskaltzaindia, the Academy of the Basque Language. In spite of some justifiable criticism of an imbalance towards unusual and archaic forms and a tendency to ignore the Romance influence on Basque, he is considered one of the greatest scholars of Basque to date.

The ikurrina flag or ikurriña is a Basque symbol and the official flag of the Basque Country Autonomous Community of Spain. This flag consists of a white cross over a green saltire on a red field.

Iñaki is a male given name. It is a neologism created by Sabino Arana meaning Ignatius, to be a Basque language analog to "Ignacio" in Spanish, "Ignace" in French, and "Ignazio" in Italian, and an alternative to the names Eneko and Íñigo.

In the Spanish public discourse the territory traditionally inhabited by the Basques was assigned a variety of names across the centuries. Terms used might have been almost identical, with hardly noticeable difference in content and connotation, or they could have varied enormously, also when consciously used one against another. The names used demonstrate changing perceptions of the area and until today the nomenclature employed could be battleground between partisans of different options.

Alejandro María Daniel Irujo Urra (1862-1911) was a Spanish lawyer. In popular discourse he is known as father of Manuel Irujo Ollo, a Basque political leader. In scholarly historiographic realm he is acknowledged mostly as defense attorney of Sabino Arana during his trials of 1896 and 1902. Politically Irujo is considered a typical case of an identity located in-between Carlism and emerging Spain's peripheral nationalisms, in this case the Basque one.