Forces

Seleucid Army

Antiochus' army was composed of 5,000 lightly armed Daae, Carmanians, and Cilicians under Byttacus the Macedonian, 10,000 Phalangites (the Argyraspides or Silver Shields) under Theodotus the Aetolian, the man who had betrayed Ptolemy and handed much of Coele Syria and Phoenicia over to Antiochus, 20,000 Macedonian Phalangites under Nicarchus and Theodotus Hemiolius, 2,000 Persian and Agrianian archers and slingers with 2,000 Thracians under Menedemus (Μενέδημος) of Alabanda, 5,000 Medes, Cissians, Cadusii, and Carmanians under the Aspasianus the Mede, 10,000 Arabians under Zabdibelus, 5,000 Greek mercenaries under Hippolochus the Thessalian, 1,500 Cretans under Eurylochus, 1,000 Neocretans under Zelys the Gortynian, and 500 Lydian javelineers and 1,000 Cardaces (Kardakes) under Lysimachus the Gaul.

Four thousand horse under Antipater, the nephew of the King and 2,000 under Themison formed the cavalry and 102 war elephants of Aryan Indian stock marched under Philip and Myischos.

Ptolemaic Army

Ptolemy had just ended a major recruitment and retraining plan with the help of many mercenary generals. His forces consisted of 3,000 Hypaspists under Eurylochus the Magnesian (the Agema), 2,000 peltasts under Socrates the Boeotian, 25,000 Macedonian Phalangites under Andromachus the Aspendian and Ptolemy, the son of Thraseas, and 8,000 Greek mercenaries under Phoxidas the Achaean, and 2,000 Cretan under Cnopias of Allaria and 1,000 Neocretan archers under Philon the Cnossian. He had another 3,000 Libyans under Ammonius the Barcian and 20,000 Egyptians under his chief minister Sosibius trained in the Macedonian way. These Egyptians were trained to fight alongside the Macedonians. Apart from these he also employed 4,000 Thracians and Gauls from Egypt and another 2,000 from Europe under Dionysius the Thracian. [2]

His Household Cavalry (tis aulis) numbered 700 men and the local (egchorioi) and Libyan horse, another 2,300 men, had as appointed general Polycrates of Argos. Those from Greece and the mercenaries were led by Echecrates the Thessalian. Ptolemy's force was accompanied by 73 elephants of the African stock.

According to Polybius, Ptolemy had 70,000 infantry, 5,000 cavalry, and 73 war elephants and Antiochus 62,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry, and 102 elephants. [3]

Battle

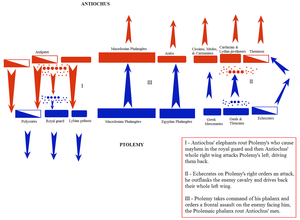

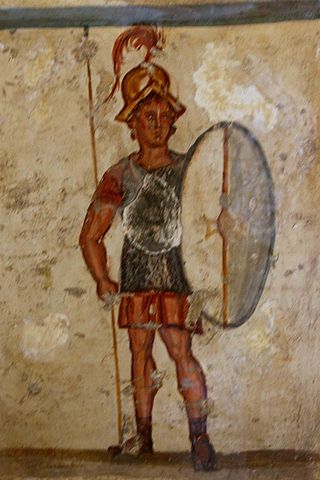

After five days of skirmishing, the two kings decided to array their troops for battle. Both placed their Phalangites in the center. Next to them they fielded the lightly armed and the mercenaries in front of which they placed their elephants and even further in the wings their cavalry. They spoke to their soldiers, took their places in the lines – Ptolemy in his left and Antiochus in his right wing – and the battle commenced.

In the beginning of the battle, the elephant contingents on the wings of both armies moved to charge. Ptolemy's diminutive African elephants retreated in panic before the impact with the larger Indians and ran through the lines of friendly infantry arrayed behind them, causing disorder in their ranks. At the same time, Antiochus had led his cavalry to the right, rode past the left wing of the Ptolemaic elephants charging the enemy horse. The Ptolemaic and Seleucid phalanxes then engaged. However, while Antiochus had the Argyraspides, Ptolemy's Macedonians were bolstered by the Egyptian phalanx. At the same time, the right wing of Ptolemy was retreating and wheeling to protect itself from the panicked elephants. Ptolemy rode to the center encouraging his phalanx to attack, Polybius tells us "with alacrity and spirit". The Ptolemaic and Seleucid phalanxes engaged in a stiff and chaotic fight. On the Ptolemaic far right, Ptolemy's cavalry was routing their opponents.

Antiochus routed the Ptolemaic horse posed against him and pursued the fleeing enemy en masse, believing to have won the day, but the Ptolemaic phalanxes eventually drove the Seleucid phalanxes back and soon Antiochus realized that his judgment was wrong. Antiochus tried to ride back, but by the time he rode back, his troops were routed and could no longer be regrouped. The battle had ended.

After the battle, Antiochus wanted to regroup and make camp outside the city of Raphia but most of his men had already found refuge inside and he was thus forced to enter it himself. Then he marched to Gaza and asked Ptolemy for the customary truce to bury the dead, which he was granted.

According to Polybius, the Seleucids suffered a little under 10,000 infantry dead, about 300 horse, and 5 elephants, and 4,000 men were taken prisoner. The Ptolemaic losses were 1,500 infantry, 700 horse, and 16 elephants. Most of the Ptolemies' elephants were captured by the Seleucids. [8]

Aftermath

Ptolemy's victory secured the province of Coele-Syria for Egypt, but it was only a respite; at the Battle of Panium in 200 BC Antiochus defeated the army of Ptolemy's young son, Ptolemy V Epiphanes and recaptured Coele Syria and Judea.

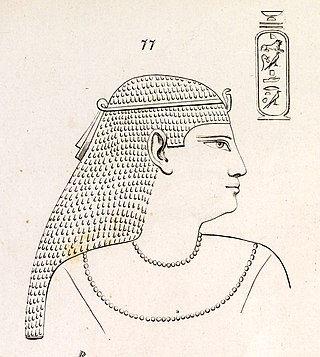

Ptolemy owed his victory in part to having a properly equipped and trained native Egyptian phalanx, which for the first time formed a large proportion of his phalangitis, thus ending his manpower problems. The self-confidence the native Egyptians gained was credited by Polybius as one of the causes of the secession in 207–186 of Upper Egypt under pharaohs Hugronaphor and Ankhmakis, who created a separate kingdom that lasted nearly twenty years.

The battle of Raphia marked a turning-point in Ptolemaic history. The native Egyptian element in 2nd-century Ptolemaic administration and culture grew in influence, driven in part by Egyptians having played a major role in the battle and in part by the financial pressures on the state aggravated [9] by the cost of the war itself. The stele that recorded the convocation of priests at Memphis in November 217, to give thanks for the victory was inscribed in Greek and hieroglyphic and demotic Egyptian: [10] in it, for the first time, Ptolemy is given full pharaonic honours in the Greek as well as the Egyptian texts; subsequently this became the norm. [11]

Some biblical commentators see this battle as being the one referred to in Daniel 11:11, where it says, "Then the king of the South will march out in a rage and fight against the king of the North, who will raise a large army, but it will be defeated." [12]

The Seleucid Empire was a Greek power in West Asia during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 312 BC by the Macedonian general Seleucus I Nicator, following the division of the Macedonian Empire founded by Alexander the Great, and ruled by the Seleucid dynasty until its annexation by the Roman Republic under Pompey in 63 BC.

Ptolemy IV Philopator was the fourth pharaoh of Ptolemaic Egypt from 221 to 204 BC.

Ptolemy V Epiphanes Eucharistos was the King of Ptolemaic Egypt from July or August 204 BC until his death in 180 BC.

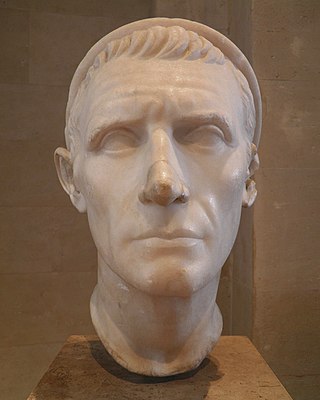

Antiochus III the Great was a Greek Hellenistic king and the 6th ruler of the Seleucid Empire, reigning from 223 to 187 BC. He ruled over the region of Syria and large parts of the rest of western Asia towards the end of the 3rd century BC. Rising to the throne at the age of eighteen in April/June 223 BC, his early campaigns against the Ptolemaic Kingdom were unsuccessful, but in the following years Antiochus gained several military victories and substantially expanded the empire's territory. His traditional designation, the Great, reflects an epithet he assumed. He also assumed the title Basileus Megas, the traditional title of the Persian kings. A militarily active ruler, Antiochus restored much of the territory of the Seleucid Empire, before suffering a serious setback, towards the end of his reign, in his war against Rome.

Cleopatra I Syra was a princess of the Seleucid Empire, Queen of Ptolemaic Egypt by marriage to Ptolemy V of Egypt, and regent of Egypt during the minority of their son, Ptolemy VI, from her husband's death in 180 BC until her own death in 176 BC.

The Battle of Magnesia took place in either December 190 or January 189 BC. It was fought as part of the Roman–Seleucid War, pitting forces of the Roman Republic led by the consul Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus and the allied Kingdom of Pergamon under Eumenes II against a Seleucid army of Antiochus III the Great. The two armies initially camped northeast of Magnesia ad Sipylum in Asia Minor, attempting to provoke each other into a battle on favorable terrain for several days.

The Battle of Ipsus was fought between some of the Diadochi in 301 BC near the town of Ipsus in Phrygia. Antigonus I Monophthalmus, the Macedonian ruler of large parts of Asia, and his son Demetrius were pitted against the coalition of three other successors of Alexander: Cassander, ruler of Macedon; Lysimachus, ruler of Thrace; and Seleucus I Nicator, ruler of Babylonia and Persia. Only one of these leaders, Lysimachus, had actually been one of Alexander's somatophylakes.

Coele-Syria was a region of Syria in classical antiquity. The term originally referred to the "hollow" Beqaa Valley between the Lebanon and the Anti-Lebanon mountain ranges, but sometimes it was applied to a broader area of the region of Syria. The area is now part of modern-day Syria and Lebanon.

The Battle of the Oenoparus took place in 145 BC on the Oenoparus river in the adjoining countryside of Antioch on the Orontes, the capital of the Seleucid Empire. It was fought between a coalition of Ptolemaic Egypt led by Ptolemy VI and Seleucids who favored the royal claim of Demetrius II Nicator against Seleucids who favored the claim of Alexander Balas. Both the Seleucid Empire and the Ptolemaic kingdom were diadochi, Greek-ruled successor states established after the conquests of Alexander the Great.

Sosibius was the chief minister of Ptolemy IV Philopator, king of Egypt. Nothing is known of his origin or parentage, though he may have been a son of Sosibius of Tarentum; nor is there any account of how he rose to power. He is first attested immediately after the accession of Ptolemy IV in 221 BC, exercising great influence over the 22-year old king alongside Agathocles, the brother of Ptolemy IV's mistress Agathoclea. He remained a major force throughout the reign and helped ensure the smooth succession of Ptolemy V Epiphanes in 204 BC. After that he disappears from the record.

Theodotus Hemiolius was a general in the service of king Antiochus III the Great, who was sent by the king in 222 BC, together with Xenon, against Molon, satrap of Media, who had raised the standard of revolt in the eastern provinces of the Seleucid Empire. However, the two generals were unable to control the rebel satrap and withdrew within the walls of the cities, leaving him in possession of the open country.

Nicarchus or Nicarch was one of the generals of the Seleucid king Antiochus III the Great. He served in Coele-Syria in the war between Antiochus and Ptolemy Philopator. Together with Theodotus he superintended the siege of Rabbatamana, and with the same general headed the phalanx at the battle of Raphia in 217 BC.

Theodotus was an Aetolian general, who at the accession of the Seleucid monarch, Antiochus III the Great, held the command of the important province of Coele-Syria for Ptolemy Philopator, king of Egypt.

The Battle of Panium was fought in 200 BC near Paneas between Seleucid and Ptolemaic forces as part of the Fifth Syrian War. The Seleucids were led by Antiochus III the Great, while the Ptolemaic army was led by Scopas of Aetolia. The Seleucids achieved a complete victory, annihilating the Ptolemaic army and conquering the province of Coele-Syria. The Ptolemaic Kingdom never recovered from its defeat at Panium and ceased to be an independent great power. Antiochus secured his southern flank and began to concentrate on the looming conflict with the Roman Republic.

The Syrian Wars were a series of six wars between the Seleucid Empire and the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, successor states to Alexander the Great's empire, during the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC over the region then called Coele-Syria, one of the few avenues into Egypt. These conflicts drained the material and manpower of both parties and led to their eventual destruction and conquest by Rome and Parthia. They are briefly mentioned in the biblical Books of the Maccabees.

The Hellenistic armies is a term which refers to the various armies of the successor kingdoms to the Hellenistic period, emerging soon after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, when the Macedonian empire was split between his successors, known as the Diadochi.

The Seleucid army was the army of the Seleucid Empire, one of the numerous Hellenistic states that emerged after the death of Alexander the Great.

The Antigonid Macedonian army was the army that evolved from the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia in the period when it was ruled by the Antigonid dynasty from 276 BC to 168 BC. It was seen as one of the principal Hellenistic fighting forces until its ultimate defeat at Roman hands at the Battle of Pydna in 168 BC. However, there was a brief resurgence in 150-148 during the revolt of Andriscus, a supposed heir to Perseus.

The Ptolemaic army was the army of the Ptolemaic Greek kings that ruled Egypt from 305 to 30 BC. Like most of the other armies of the Diadochi, it was very much Macedonian in style, with the use of the long pike (sarissa) in a deep phalanx formation. Despite the strength of the Ptolemaic army, evinced in 217 BC with the victory over the Seleucids at the Battle of Raphia, the Ptolemaic Kingdom itself fell into decline and by the time of Julius Caesar, it was but a mere client-kingdom of the Roman Republic. The army by the time of Caesar’s campaigns in the eastern Mediterranean was a mere shadow of its former self: generally, a highly disorganized assemblage of mercenaries and other foreign troops.

Polycrates of Argos, son of Mnasiades, was a Ptolemaic commander at the Battle of Raphia, as well as a governor of Cyprus and chancellor of the Ptolemaic Kingdom in the late third and early second centuries BC.