Agathocles was a Greek tyrant of Syracuse (317–289 BC) and self-styled king of Sicily (304–289 BC).

This article concerns the period 309 BC – 300 BC.

Hamilcar Barca or Barcas was a Carthaginian general and statesman, leader of the Barcid family, and father of Hannibal, Hasdrubal and Mago. He was also father-in-law to Hasdrubal the Fair.

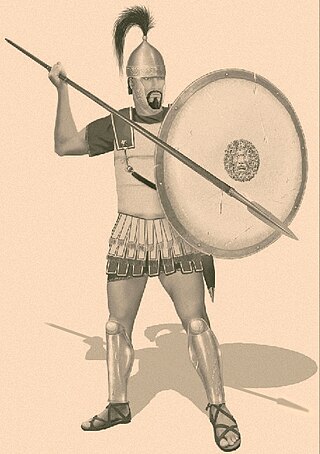

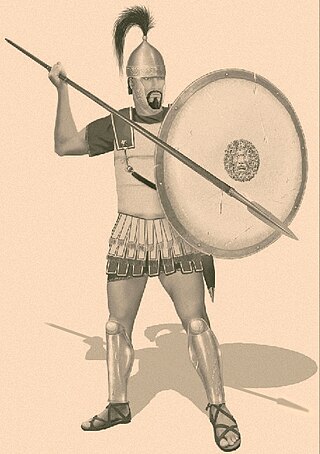

The Sacred Band of Carthage is the name used by ancient Greek historians to refer to an elite infantry unit of Carthaginian citizens that served in military campaigns during the fourth century BC. It is unknown how they identified themselves or whether they were considered a distinct formation.

The Battle of the Crimissus was fought in 339 BC between a large Carthaginian army commanded by Asdrubal and Hamilcar and an army from Syracuse led by Timoleon. Timoleon attacked the Carthaginian army by surprise near the Crimissus river in western Sicily and won a great victory. When he defeated another much smaller force of Carthaginians shortly afterwards, Carthage sued for peace. The peace allowed the Greek cities on Sicily to recover and began a period of stability. However, another war between Syracuse and Carthage erupted after Timoleon's death, not long after Agathocles seized power in 317 BC.

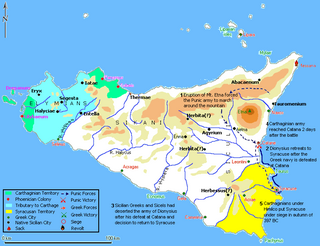

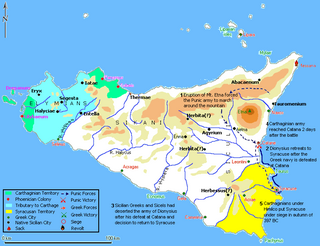

The Battle of the Himera River was fought in 311 BC between Carthage and Syracuse near the mouth of the Himera river. Hamilcar, grandson of Hanno the Great, led the Carthaginians, while the Syracusans were led by Agathocles. Agathocles initially surprised the Carthaginians with an attack on their camp, but the Greeks lost the battle when they were attacked by unexpected Carthaginian reinforcements. The Greek army took many casualties as it retreated. Agathocles managed to gather the remains of his army and retreat to Syracuse, but lost control of Sicily.

The siege of Syracuse in 397 BC was the first of four unsuccessful sieges Carthaginian forces would undertake against Syracuse from 397 to 278 BC. In retaliation for the siege of Motya by Dionysius of Syracuse, Himilco of the Magonid family of Carthage led a substantial force to Sicily. After retaking Motya and founding Lilybaeum, Himilco sacked Messana, then laid siege to Syracuse in the autumn of 397 BC after the Greek navy was crushed at Catana.

The Sicilian Wars, or Greco-Punic Wars, were a series of conflicts fought between ancient Carthage and the Greek city-states led by Syracuse over control of Sicily and the western Mediterranean between 580 and 265 BC.

The city of Carthage was founded in the 9th century BC on the coast of Northwest Africa, in what is now Tunisia, as one of a number of Phoenician settlements in the western Mediterranean created to facilitate trade from the city of Tyre on the coast of what is now Lebanon. The name of both the city and the wider republic that grew out of it, Carthage developed into a significant trading empire throughout the Mediterranean. The date from which Carthage can be counted as an independent power cannot exactly be determined, and probably nothing distinguished Carthage from the other Phoenician colonies in Northwest Africa and the Mediterranean during 800–700 BC. By the end of the 7th century BC, Carthage was becoming one of the leading commercial centres of the West Mediterranean region. After a long conflict with the emerging Roman Republic, known as the Punic Wars, Rome finally destroyed Carthage in 146 BC. A Roman Carthage was established on the ruins of the first. Roman Carthage was eventually destroyed—its walls torn down, its water supply cut off, and its harbours made unusable—following its conquest by Arab invaders at the close of the 7th century. It was replaced by Tunis as the major regional centre, which has spread to include the ancient site of Carthage in a modern suburb.

Near the site of the first battle and great Carthaginian defeat of 480 BC, the Second Battle of Himera was fought near the city of Himera in Sicily in 409 between the Carthaginian forces under Hannibal Mago and the Ionian Greeks of Himera aided by an army and a fleet from Syracuse. Hannibal, acting under the instructions of the Carthaginian senate, had previously sacked and destroyed the city of Selinus after the Battle of Selinus in 409. Hannibal then destroyed Himera which was never rebuilt. Mass graves associated with this battle were discovered in 2008-2011, corroborating the stories told by ancient historians.

The Battle of Messene took place in 397 BC in Sicily. Carthage, in retaliation for the attack on Motya by Dionysius, had sent an army under Himilco, to Sicily to regain lost territory. Himilco sailed to Panormus, and from there again sailed and marched along the northern coast of Sicily to Cape Pelorum, 12 miles (19 km) north of Messene. While the Messenian army marched out to offer battle, Himilco sent 200 ships filled with soldiers to the city itself, which was stormed and the citizens were forced to disperse to forts in the countryside. Himilco later sacked and leveled the city, which was again rebuilt after the war.

The Battle of Abacaenum took place between the Carthaginian forces under Mago and the Siceliot army under Dionysius in 393 BC near the Sicilian town on Abacaenum in north-eastern Sicily. Dionysius, tyrant of Syracuse, had been expanding his influence over Sicels' territories in Sicily. After Dionysius' unsuccessful siege in 394 BC of Tauromenium, a Carthaginian ally, Mago decided to attack Messana. However, the Carthaginian army was defeated by the Greeks near the town of Abacaenum and had to retire to the Carthaginian territories in Western Sicily. Dionysius did not attack the Carthaginians but continued to expand his influence in eastern Sicily.

The Battle of Chrysas was a battle fought in 392 BC in the course of the Sicilian Wars, between the Carthaginian army under Mago and a Greek army under Dionysius I, tyrant of Syracuse, who was aided by Agyris, tyrant of the Sicel city of Agyrium. Mago had been defeated by Dionysius at Abacaenum in 393, which had not damaged the Carthaginian position in Sicily. Reinforced by Carthage in 392, Mago moved to attack the Sicles allied with Syracuse in central Sicily. After the Carthaginians reached and encamped near the river Chrysas, the Sicels harassed the Carthaginian supply lines causing a supply shortage, while the Greek soldiers rebelled and deserted Dionysius when he refused to fight a pitched battle. Both Mago and Dionysius agreed to a peace treaty, which allowed the Carthaginians to formally occupy the area west of the River Halycus, while Dionysius was given lordship over the Sicel lands. The peace would last until 383, when Dionysius attacked the Carthaginians again.

Himilco was a member of the Magonids, a Carthaginian family of hereditary generals, and had command over the Carthaginian forces between 406 BC and 397 BC. He is chiefly known for his war in Sicily against Dionysius I of Syracuse.

The siege of Segesta took place either in the summer of 398 BC or the spring of 397 BC. Dionysius the Elder, tyrant of Syracuse, after securing peace with Carthage in 405 BC, had steadily increased his military power and tightened his grip on Syracuse. He had fortified Syracuse against sieges and had created a large army of mercenaries and a large fleet, in addition to employing catapults and quinqueremes for the first time in history. In 398 BC he attacked and sacked the Phoenician city of Motya despite a Carthaginian relief effort led by Himilco II of Carthage. While Motya was under siege, Dionysius besieged and assaulted Segesta unsuccessfully. Following the sack of Motya, Segesta again came under siege by Greek forces, but the Elymian forces based in Segesta managed to inflict damage on the Greek camp in a daring night assault. When Himilco of Carthage arrived in Sicily with the Carthaginian army in the spring of 397 BC, Dionysius withdrew to Syracuse. The failure of Dionysius to secure a base in western Sicily meant the main events of the Second Sicilian war would be acted out mostly in eastern Sicily, sparing the Elymian and Phoenician cities the ravages of war until 368 BC.

The siege and subsequent sacking of Camarina took place in 405 BC during the Sicilian Wars.

The siege of Syracuse by the Carthaginians from 311 to 309 BC followed shortly after the Battle of the Himera River in the same year. In that battle the Carthaginians, under the leadership of Hamilcar the son of Gisco, had defeated the tyrant of Syracuse, Agathocles. Agathocles had to retreat to Syracuse and lost control over the other Greek cities on Sicily, who went over to the Carthaginian side.

The siege of Syracuse from 344 to 343/342 BC was part of a war between the Syracusan general Hicetas and the tyrant of Syracuse, Dionysius II. The conflict became more complex when Carthage and Corinth became involved. The Carthaginians had made an alliance with Hicetas to expand their power in Sicily. Somewhat later, the Corinthian general Timoleon arrived in Sicily to restore democracy to Syracuse. With the assistance of several other Sicilian Greek cities, Timoleon emerged victorious and reinstated a democratic regime in Syracuse. The siege is described by the ancient historians Diodorus Siculus and Plutarch, but there are important differences in their accounts.

The siege of Syracuse in 278 BC was the last attempt of Carthage to conquer the city of Syracuse. Syracuse was weakened by a civil war between Thoenon and Sostratus. The Carthaginians used this opportunity to attack and besiege Syracuse both by land and sea. Thoenon and Sostratus then appealed to king Pyrrhus of Epirus to come to the aid of Syracuse. When Pyrrhus arrived, the Carthaginian army and navy retreated without a fight.

Antander was a man of Syracuse, Magna Graecia, of the 3rd and 4th centuries BCE. He was the older brother of Agathocles, king of Syracuse, and was a commander -- or strategos -- of the troops sent by the Syracusans to the relief of Crotona when it was besieged by the Bruttii tribe in 317.