Related Research Articles

A goddess is a female deity. In many known cultures, goddesses are often linked with literal or metaphorical pregnancy or imagined feminine roles associated with how women and girls are perceived or expected to behave. This includes themes of spinning, weaving, beauty, love, sexuality, motherhood, domesticity, creativity, and fertility. Many major goddesses are also associated with magic, war, strategy, hunting, farming, wisdom, fate, earth, sky, power, laws, justice, and more. Some themes, such as discord or disease, which are considered negative within their cultural contexts also are found associated with some goddesses. There are as many differently described and understood goddesses as there are male, shapeshifting, or neuter gods.

In Mesopotamian religion, Tiamat is a primordial goddess of the sea, mating with Abzû, the god of the groundwater, to produce younger gods. She is the symbol of the chaos of primordial creation. She is referred to as a woman and described as "the glistening one". It is suggested that there are two parts to the Tiamat mythos. In the first, she is a creator goddess, through a sacred marriage between different waters, peacefully creating the cosmos through successive generations. In the second Chaoskampf Tiamat is considered the monstrous embodiment of primordial chaos. Some sources identify her with images of a sea serpent or dragon.

A mother goddess is a major goddess characterized as a mother or progenitor, either as an embodiment of motherhood and fertility or fulfilling the cosmological role of a creator- and/or destroyer-figure, typically associated the Earth, sky, and/or the life-giving bounties thereof in a maternal relation with humanity or other gods. When equated in this lattermost function with the earth or the natural world, such goddesses are sometimes referred to as the Mother Earth or Earth Mother, deity in various animistic or pantheistic religions. The earth goddess is archetypally the wife or feminine counterpart of the Sky Father or Father Heaven, particularly in theologies derived from the Proto-Indo-European sphere. In some polytheistic cultures, such as the Ancient Egyptian religion which narrates the cosmic egg myth, the sky is instead seen as the Heavenly Mother or Sky Mother as in Nut and Hathor, and the earth god is regarded as the male, paternal, and terrestrial partner, as in Osiris or Geb who hatched out of the maternal cosmic egg.

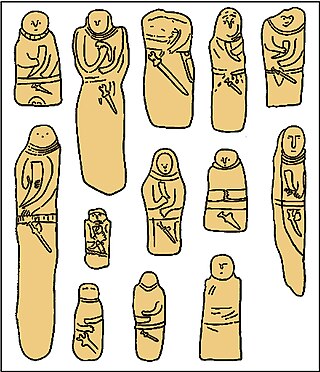

The Nommo or Nummo are primordial ancestral spirits in Dogon religion and cosmogony venerated by the Dogon people of Mali. The word Nommos is derived from a Dogon word meaning "to make one drink." Nommos are usually described as amphibious, hermaphroditic, fish-like creatures. Folk art depictions of Nommos show creatures with humanoid upper torsos, legs/feet, and a fish-like lower torso and tail. Nommos are also referred to as "Masters of the Water", "the Monitors", and "the Teachers". Nommo can be a proper name of an individual or can refer to the group of spirits as a whole. For purposes of this article, "Nommo" refers to a specific individual and "Nommos" is used to reference the group of beings.

The Bambara are a Mandé ethnic group native to much of West Africa, primarily southern Mali, Ghana, Guinea, Burkina Faso and Senegal. They have been associated with the historic Bambara Empire. Today, they make up the largest Mandé ethnic group in Mali, with 80% of the population speaking the Bambara language, regardless of ethnicity.

Proto-Indo-European mythology is the body of myths and deities associated with the Proto-Indo-Europeans, speakers of the hypothesized Proto-Indo-European language. Although the mythological motifs are not directly attested – since Proto-Indo-European speakers lived in preliterate societies – scholars of comparative mythology have reconstructed details from inherited similarities found among Indo-European languages, based on the assumption that parts of the Proto-Indo-Europeans' original belief systems survived in the daughter traditions.

In creation myths, the term "Five Suns" refers to the belief of certain Nahua cultures and Aztec peoples that the world has gone through five distinct cycles of creation and destruction, with the current era being the fifth. It is primarily derived from a combination of myths, cosmologies, and eschatological beliefs that were originally held by pre-Columbian peoples in the Mesoamerican region, including central Mexico, and it is part of a larger mythology of Fifth World or Fifth Sun beliefs.

In Mande mythology, Faro purified the earth by sacrificing himself to atone for his twin Pemba's sin.

The rainbow has been a favorite component of mythology throughout history. Rainbows are part of the myths of many cultures around the world. The Norse saw it as Bifrost; Abrahamic traditions see it as a covenant with God not to destroy the world by means of floodwater. Whether as a bridge to the heavens, messenger, archer's bow, or serpent, the rainbow has been pressed into symbolic service for millennia. There are myriad beliefs concerning the rainbow. The complex diversity of rainbow myths are far-reaching, as are their inherent similarities.

The Goddess movement is a revivalistic Neopagan religious movement which includes spiritual beliefs and practices that emerged predominantly in the Western world during the 1970s. The movement grew as a reaction both against Abrahamic religions, which exclusively have gods with whom are referred by masculine grammatical articles and pronouns, and secularism. It revolves around Goddess worship and the veneration for the divine feminine, and may include a focus on women or on one or more understandings of gender or femininity.

A Chiwara is a ritual object representing an antelope, used by the Bambara ethnic group in Mali. The Chiwara initiation society uses Chiwara masks, as well as dances and rituals associated primarily with agriculture, to teach young Bamana men social values as well as agricultural techniques.

The Thracian religion comprised the mythology, ritual practices and beliefs of the Thracians, a collection of closely related ancient Indo-European peoples who inhabited eastern and southeastern Europe and northwestern Anatolia throughout antiquity and who included the Thracians proper, the Getae, the Dacians, and the Bithynians. The Thracians themselves did not leave an extensive written corpus of their mythology and rituals, but information about their beliefs is nevertheless available through epigraphic and iconographic sources, as well as through ancient Greek writings.

Snakes are a common occurrence in myths for a multitude of cultures. The Hopi people of North America viewed snakes as symbols of healing, transformation, and fertility. Snakes in Mexican folk culture tell about the fear of the snake to the pregnant women where the snake attacks the umbilical cord. The Great Goddess often had snakes as her familiars—sometimes twining around her sacred staff, as in ancient Crete—and they were worshipped as guardians of her mysteries of birth and regeneration. Although not entirely a snake, the plumed serpent, Quetzalcoatl, in Mesoamerican culture, particularly Mayan and Aztec, held a multitude of roles as a deity. He was viewed as a twin entity which embodied that of god and man and equally man and serpent, yet was closely associated with fertility. In ancient Aztec mythology, Quetzalcoatl was the son of the fertility earth goddess, Cihuacoatl, and cloud serpent and hunting god, Maxicoat. His roles took the form of everything from bringer of morning winds and bright daylight for healthy crops, to a sea god capable of bringing on great floods. As shown in the images there are images of the sky serpent with its tail in its mouth, it is believed to be a reverence to the sun, for which Quetzalcoatl was also closely linked.

The traditional Mayas generally assume the Moon to be female, and the Moon's perceived phases are accordingly conceived as the stages of a woman's life. The Maya moon goddess wields great influence in many areas. Being in the image of a woman, she is associated with sexuality and procreation, fertility and growth, not only of human beings, but also of the vegetation and the crops. Since growth can also cause all sorts of ailments, the moon goddess is also a goddess of disease. Everywhere in Mesoamerica, including the Mayan area, she is specifically associated with water, be it wells, rainfall, or the rainy season. In the codices, she has a terrestrial counterpart in goddess I.

The Scythian religion refers to the mythology, ritual practices and beliefs of the Scythian cultures, a collection of closely related ancient Iranic peoples who inhabited Central Asia and the Pontic–Caspian steppe in Eastern Europe throughout Classical Antiquity, spoke the Scythian language, and which included the Scythians proper, the Cimmerians, the Sarmatians, the Alans, the Sindi, the Massagetae and the Saka.

Egyptian mythology is the collection of myths from ancient Egypt, which describe the actions of the Egyptian gods as a means of understanding the world around them. The beliefs that these myths express are an important part of ancient Egyptian religion. Myths appear frequently in Egyptian writings and art, particularly in short stories and in religious material such as hymns, ritual texts, funerary texts, and temple decoration. These sources rarely contain a complete account of a myth and often describe only brief fragments.

Akan religion comprises the traditional beliefs and religious practices of the Akan people of Ghana and eastern Ivory Coast. Akan religion is referred to as Akom. Although most Akan people have identified as Christians since the early 20th century, Akan religion remains practiced by some and is often syncretized with Christianity. The Akan have many subgroups, so the religion varies greatly by region and subgroup. Similar to other traditional religions of West and Central Africa such as West African Vodun, Yoruba religion, or Odinani, Akan cosmology consists of a senior god who generally does not interact with humans and many gods who assist humans.

The Mandé creation narrative is the traditional creation myth of the Mandinka of southern Mali.

A hogon is a spiritual leader in a Dogon village who plays an important role in Dogon religion.

The Lebe or Lewe is a Dogon religious, secret institution and primordial ancestor, who arose from a serpent. According to Dogon cosmogony, Lebe is the reincarnation of the first Dogon ancestor who, resurrected in the form of a snake, guided the Dogons from the Mandé to the cliff of Bandiagara where they are found today.

References

- 1 2 3 Appiah, Anthony; Gates (Jr.), Henry Louis (2005). Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517055-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Imperato, Gavin H.; Imperato, Pascal James (2006-06-01). "Beliefs and practices concerning twins, hermaphrodites, and albinos among the Bamana and Maninka of Mali". Journal of Community Health. 31 (3): 198–224. doi:10.1007/s10900-005-9011-3. ISSN 1573-3610. PMID 16830507. S2CID 29480078.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lugira, Aloysius Muzzanganda (2009). African Traditional Religion. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-2047-8.

- ↑ Pitek, Emily (2018). "Bambara also known as "Bamana"". doi:10.14288/1.0375675.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 Gomez, Michael A. (2000-11-09). Exchanging Our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-6171-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Lynch, Patricia Ann; Roberts, Jeremy (2010). African Mythology, A to Z. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-3133-7.

- ↑ Dieterlen, Germaine (1957). "The Mande Creation Myth". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 27 (2): 124–138. doi:10.2307/1156806. ISSN 0001-9720. JSTOR 1156806. S2CID 146579204.

- ↑ "Encyclopedia of African Religion". SAGE Publications Inc. 2021-03-20. Retrieved 2021-03-21.

- ↑ Mellott, Noal (1984-04-01). "Summaries of sacrificial rites described in the preceding four issues of Systèmes de pensée en Afrique noire". Systèmes de pensée en Afrique noire (6): 149–183. doi: 10.4000/span.555 . ISSN 0294-7080.