Related Research Articles

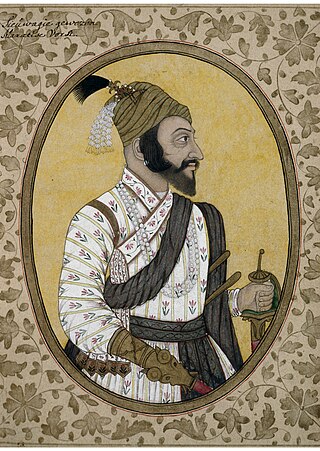

Shivaji I was an Indian ruler and a member of the Bhonsle Dynasty. Shivaji carved out his own independent kingdom from the declining Adilshahi Sultanate of Bijapur that formed the genesis of the Maratha Empire. In 1674, he was formally crowned the Chhatrapati of his realm at Raigad Fort.

Kshatriya is one of the four varnas of Hindu society and is associated with the warrior aristocracy. The Sanskrit term kṣatriyaḥ is used in the context of later Vedic society wherein members were organised into four classes: brahmin, kshatriya, vaishya, and shudra.

The Maratha caste is composed of 96 clans, originally formed in the earlier centuries from the amalgamation of families from the peasant (Kunbi), shepherd (Dhangar), blacksmith (Lohar), carpenter (Sutar), Bhandari, Thakar and Koli castes in Maharashtra. Many of them took to military service in the 16th century for the Deccan sultanates or the Mughals. Later in the 17th and 18th centuries, they served in the armies of the Maratha Empire, founded by Shivaji, a Maratha Kunbi by caste. Many Marathas were granted hereditary fiefs by the Sultanates, and Mughals for their service.

Kayastha or Kayasth denotes a cluster of disparate Indian communities broadly categorised by the regions of the Indian subcontinent in which they were traditionally located—the Chitraguptavanshi Kayasthas of North India, the Chandraseniya Kayastha Prabhus of Maharashtra, the Bengali Kayasthas of Bengal and Karanas of Odisha. All of them were traditionally considered "writing castes", who had historically served the ruling powers as administrators, ministers and record-keepers.

Jijabai Bhonsle (or Bhonsale, Bhosale, Bhosle) or Jadhav, referred to as Rajmata, Rastramata, Jijabai, Jijamata or Jijau, was the mother of Chattrapati Shivaji, founder of the Maratha Empire. She was a daughter of Lakhujirao Jadhav of Sindkhed Raja.

Kunbi is a generic term applied to several castes of traditional farmers in Western India. These include the Dhonoje, Ghatole, Masaram, Hindre, Jadav, Jhare, Khaire, Lewa, Lonare and Tirole communities of Vidarbha. The communities are largely found in the state of Maharashtra but also exist in the states of Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Karnataka, Kerala and Goa. Kunbis are included among the Other Backward Classes (OBC) in Maharashtra.

Shahu of the Bhonsle dynasty of Marathas was a Raja and the first Maharaja (1900–1922) of the Indian princely state of Kolhapur. Rajarshi Shahu was considered a true democrat and social reformer. Shahu Maharaj was an able ruler who was associated with many progressive policies during his rule. From his coronation in 1894 till his demise in 1922, he worked for the cause of the lower caste subjects in his state. Primary education to all regardless of caste and creed was one of his most significant priorities.

The Dhangars are a herding caste of people found in the Indian states of Maharashtra, Karnataka, Goa, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. They are referred as Gavli in southern Maharashtra, Goa and northern Karnataka, Golla in Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka and Ahir in northern Maharashtra. Some Gavlis live in forested hill tracts of India's Western Ghats. Gavli, also known as Dange or Mhaske, and Ahir are a sub-caste of Dhangar. However, there are many distinct Gavli castes in Maharashtra and Dhangar Gavli is one of them.

The Maratha Clan System, refers to the 96 Maratha clans.The clans together form the Maratha caste of India. These Marathas primarily reside in the Indian state of Maharashtra, with smaller regional populations in other states.

Chandraseniya Kayastha Prabhu (CKP) or historically and commonly known as Chandraseniya Prabhu or just Prabhu is an ethnic group mainly found in Gujarat and Maharashtra. Historically, they made equally good warriors, statesmen as well as writers. They held the posts such as Deshpande and Gadkari according to the historian, B.R. Sunthankar, produced some of the best warriors in Maharashtrian history.

The caste system in Goa consists of various Jātis or sub-castes found among Hindus belonging to the four varnas, as well as those outside of them. A variation of the traditional Hindu caste system was also retained by the Goan Catholic community.

The Bhandari(also know as "siyal" in Odisha)community is a caste that inhabits the western coast of India. Their traditional occupation was "toddy tapping". They form the largest caste group in the state of Goa, reportedly being over 30% of that state's Hindu population, and play a major role in deciding the future of any political party there. Bhandaris are included in the list of Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in Goa and Maharashtra.

The Shirke is a clan (Gotra) found in several castes such as Koli, Maratha, Agri, found largely in Maharashtra and bordering states of India.

Shivaji was the founder of the Maratha Empire in the Indian subcontinent. This article describes Shivaji's life from his birth until the age of 19 years (1630–1649).

Vishweshwara Pandit, popularly known as Gaga Bhatt, was a 17th-century Brahmin scholar from Varanasi, best known for presiding over the pan-Indian Brahminical committees convened by Shivaji to adjudicate the caste status of the Syenavi Gaud Saraswat Brahmins, who claimed Brahmin rank, and the Chandraseniya Kayastha Prabhus, who claimed to be Kshatriyas, before taking up the matter of Shivaji's own caste and eligibility for investiture with the sacred thread (Upanayana), coronation as Chhatrapati (Abhisheka), and participation in other high rituals.

The following list includes a brief about the titles of nobility or orders of chivalry used by the Marathas of India and by the Marathis/Konkanis in general.

Modern historians agree that Rajputs consisted of a mix of various different social groups and different varnas. Rajputisation explains the process by which such diverse communities coalesced into the Rajput community.

Bhāt is a "generic term" used to refer to a bard in India. The majority of Bhats hail from Rajasthan and worked as genealogists for their patrons, however, they are viewed as mythographers. In India, the inception of Rajputization was followed by the emanation of two groups of bards with a group of them serving the society's influential communities and the other serving the communities with lower ranking in the social hierarchy.

Ghorpade is a surname and family name found among Marathas, Marathi Brahmins, Mahar and even Chambhar caste in the Indian states of Maharashtra and Karnataka and may refer to members of the Ghorpade Dynasty.

The Bhonsle dynasty are a prominent Indian Marathi royal house. They claimed descent from the Rajput Sisodia dynasty, but were likely Kunbi Marathas.

References

- ↑ Kulkarni, Prashant P. (6 June 1990). "Coinage of the Bhonsla Rajas of Nagpur". Indian Coin Society.

- 1 2 3 Vendell, Dominic (2018). Scribes and the Vocation of Politics in the Maratha Empire, 1708-1818 (Thesis). Columbia University.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Vajpeyi, Ananya (2005). "Excavating Identity through Tradition: Who was Shivaji?". In Varma, Supriya; Saberwal, Satish (eds.). Traditions in Motion: Religion and Society in History. Oxford University Press. pp. 239–268. ISBN 9780195669152.Edited version of Ananya, Vajpeyi (August 2004). "Making a Śūdra King: The Royal Consecration of Shivaji". Politics of complicity, poetics of contempt: A history of the Śūdra in Maharashtra, 1650–1950 CE (Thesis). University of Chicago. p. 155-226.

- ↑ Christophe Jaffrelot (2006). Dr Ambedkar and Untouchability: Analysing and Fighting Caste. Permanent Black. p. 39. ISBN 978-81-7824-156-2.

Obviously, Ambedkar had in mind the Brahmin's refusal to recognize Shivaji as a Kshatriya. His theory, which is based on scant historical evidence , doubtless echoed this episode in Maharashtra's history, whereas in fact Shivaji, a Maratha-Kunbi, was a Shudra. Nevertheless, he had won power and so expected the Brahmins to confirm his new status by writing for him an adequate genealogy. This process recalls that of Sanskritisation , but sociologists refer to such emulation of Kshatriyas by Shudras as ' Kshatriyaisation ' and describe it as a variant of Sanskritisation.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bayly, Susan (22 February 2001). Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age. Cambridge University Press. pp. 57–59. ISBN 9780521798426.

- 1 2 Abraham Eraly (2000). Emperors of the Peacock Throne: The Saga of the Great Mughals. Penguin Books India. p. 435. ISBN 978-0-14-100143-2.

- 1 2 Jadunath Sarkar (1992). Shivaji and His Times. Orient Longman. p. 158. ISBN 978-81-250-1347-1.

- ↑ O'Hanlon, Rosalind, ed. (1985), "Religion and society under early British rule", Caste, Conflict and Ideology: Mahatma Jotirao Phule and Low Caste Protest in Nineteenth-Century Western India, Cambridge South Asian Studies, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 13–14, ISBN 978-0-521-52308-0 , retrieved 12 July 2021

- 1 2 Feldhaus, Anne (2003), Feldhaus, Anne (ed.), "The Pilgrimage to Śiṅgṇāpūr", Connected Places: Region, Pilgrimage, and Geographical Imagination in India, Religion/Culture/Critique, New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 45–87, doi:10.1057/9781403981349_3, ISBN 978-1-4039-8134-9

- ↑ Dhavalikar, M. K. (2000). "Review of SHIKHAR SHINGANAPURCHA SRI SHAMBHU MAHADEV (In Marathi)". Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 60/61: 507–508. ISSN 0045-9801. JSTOR 42936646.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Gordon, Stewart (1993), "Shivaji (1630–80) and the Maratha polity", The Marathas 1600–1818, The New Cambridge History of India, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 86–87, ISBN 978-0-521-26883-7 , retrieved 26 June 2021

- ↑ Daniel Jasper (2003). "Commemorating the 'golden age' of Shivaji in Maharashtra, India, and the development of Maharashtrian public politics". Journal of Political and Military Sociology. 31 (2): 215. JSTOR 45293740. S2CID 152003918.

- 1 2 3 Baviskar, B. S.; Attwood, D. W. (30 October 2013). "Caste Barriers to Initiative and Innovation". Inside-Outside: Two Views of Social Change in Rural India. SAGE Publications. p. 395. ISBN 978-81-321-1865-7.

- ↑ Rajmohan Gandhi (1999). Revenge and Reconciliation. Penguin Books India. pp. 110–. ISBN 978-0-14-029045-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Busch, Allison (2011). Poetry of Kings: The Classical Hindi Literature of Mughal India. Oxford University Press. pp. 190–191. ISBN 978-0-19-976592-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Deshpande, Madhav M. (2010). "Kṣatriyas in the Kali Age? Gāgābhaṭṭa & His Opponents". Indo-Iranian Journal. 53 (2): 95–120. ISSN 0019-7246.

- 1 2 Kothiyal, Tanuja (14 March 2016). Nomadic Narratives: A History of Mobility and Identity in the Great Indian Desert. Cambridge University Press. p. 103–104. ISBN 978-1-316-67389-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Kruijtzer, Gijs (2009). Xenophobia in Seventeenth-century India. Leiden University Press. p. 143. ISBN 9789087280680.

- ↑ Sen, Surendra Nath (1958). Foreign Biographies of Shivaji (2 ed.). Calcutta: K. P. Bagchi & Company, Indian Council of Historical Research. pp. 265–267.

- 1 2 John Keay (12 April 2011). India: A History. Atlantic. p. 565. ISBN 978-0-8021-9550-0.

- ↑ Rao, Anupama (13 October 2009). "Caste Radicalism And The Making Of A New Political Subject". The Caste Question: Dalits and the Politics of Modern India. University of California Press. p. 42. doi:10.1525/9780520943377-006. ISBN 978-0-520-94337-7. S2CID 201912448.

- ↑ Krshnaji Ananta Sabhasada; Sen, Surendra Nath (1920). Siva Chhatrapati : being a translation of Sabhasad Bakhar with extracts from Chitnis and Sivadigvijya, with notes. Calcutta : University of Calcutta. pp. 260, 261.

- ↑ Truschke, Audrey (2021). "Rajput and Maratha Kingships". The Language of History: Sanskrit Narratives of Indo-Muslim Rule. Columbia University Press. pp. 183–184. ISBN 9780231551953.

- ↑ Sardesai, G. S. (1946). "Shahji: The Rising Sun". New History of the Marathas. Vol. 1. Phoenic Publications. p. 46.

- ↑ Nicholas Patrick Wiseman (1836). The Dublin Review. William Spooner. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ↑ Kulkarni, Sumitra (1995). The Satara Raj, 1818-1848: A Study in History, Administration, and Culture. Mittal Publications. ISBN 9788170995814.

- ↑ "Portuguese Studies Review". International Conference Group on Portugal. 6 June 2001.

- ↑ "The Gazetteers Department". akola.nic.in.