Petrus Comestor, also called Pierre le Mangeur, was a twelfth-century French theological writer and university teacher.

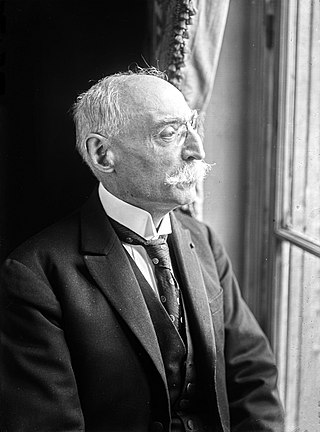

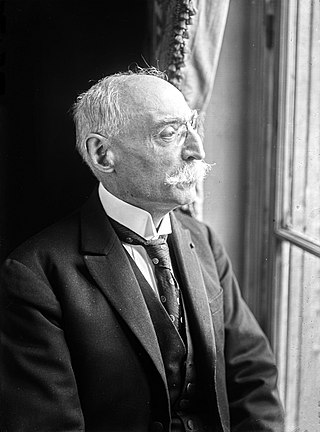

Émile Mâle was a French art historian, one of the first to study medieval, mostly sacral French art and the influence of Eastern European iconography thereon. He was a member of the Académie française, and a director of the Académie de France à Rome.

Dictionarius is a short work written about the year 1200 by the medieval English grammarian Johannes de Garlandia or John of Garland. For the use of his students at the University of Paris, he lists the trades and tradesmen that they saw around them every day in the streets of Paris, France. The work is written in Latin with interlinear glosses in Old French.

Edmond Faral was an Algerian-born French medievalist. He became in 1924 Professor of Latin literature at the Collège de France.

Régine Pernoud was a French historian and archivist. Pernoud was one of the most prolific medievalists in 20th century France; more than any other single scholar of her time, her work advanced and expanded the study of Joan of Arc.

Bible translations into French date back to the Medieval era. After a number of French Bible translations in the Middle Ages, the first printed translation of the Bible into French was the work of the French theologian Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples in 1530 in Antwerp. This was substantially revised and improved in 1535 by Pierre Robert Olivétan. This Bible, in turn, became the basis of the first French Catholic Bible, published at Leuven in 1550, the work of Nicholas de Leuze and François de Larben. Finally, the Bible de Port-Royal, prepared by Antoine Lemaistre and his brother Louis Isaac Lemaistre, finished in 1695, achieved broad acceptance among both Catholics and Protestants. Jean-Frédéric Ostervald's version (1744) also enjoyed widespread popularity.

Stjórn is the name given to a collection of Old Norse translations of Old Testament historical material dating from the 14th century, which together cover Jewish history from Genesis through to II Kings. Despite the collective title, Stjórn is not a homogeneous work. Rather, it consists of three separate works which vary in date and context, labelled Stjórn I, II and III by scholar I.J. Kirby.

Bible translations in the Middle Ages discussions are rare in contrast to Late Antiquity, when the Bibles available to most Christians were in the local vernacular. In a process seen in many other religions, as languages changed, and in Western Europe languages with no tradition of being written down became dominant, the prevailing vernacular translations remained in place, despite gradually becoming sacred languages, incomprehensible to the majority of the population in many places. In Western Europe, the Latin Vulgate, itself originally a translation into the vernacular, was the standard text of the Bible, and full or partial translations into a vernacular language were uncommon until the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period.

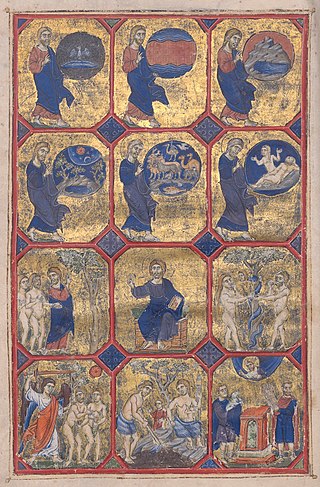

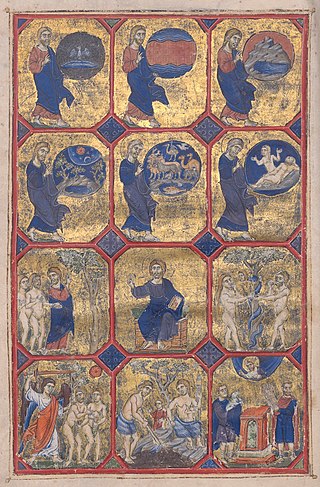

The Historia Scholastica is a Biblical paraphrase written in Medieval Latin by Petrus Comestor. Completed around 1173, he wrote it for the cathedral school of Notre Dame in Paris. Sometimes called the "Medieval Popular Bible", it draws on the Bible and other sources, including the works of classical scholars and the Fathers of the Church, to present an overview of sacred history.

Guyart des Moulins was a medieval monk. He is famous for being the author of the first Bible translation in French, the Bible Historiale.

André Vauchez FBA is a French medievalist specialising in the history of Christian spirituality. He has studied at the École normale supérieure and the École française de Rome. His thesis, defended in 1978, was published in English as Sainthood in the Later Middle Ages in 1987 and has become a standard reference work.

The Codex Theodulphianus, designated Θ, is a 10th-century Latin manuscript of the Old and New Testament. The text, written on vellum, is a version of the Latin Vulgate Bible. It contains the whole Bible, with some parts written on purple vellum.

The Faits des Romains is a Medieval work of prose written in Old French, composed in the Île-de-France, or by a native of that region, around 1213–14. It chronicles the life of Julius Caesar.

Diabolus in Musica is a French medieval music ensemble based in Tours and directed by Antoine Guerber. Guerber studied medieval music under Dominique Vellard at the Centre de Musique Médiévale de Paris and at the Early Music Department of the Conservatoire National Supérieur in Lyon.

Geneviève Hasenohr is a French philologist and prolific scholar of medieval and Renaissance French literature. She has authored or contributed to more than forty books, written at least fifty academic articles and reviews, and prepared numerous scholarly editions.

Eugénie Droz was a Swiss romance scholar, editor publisher and writer, originally from the Suisse Romande. She created the Librairie Droz, a publisher and seller of academic books, at Paris in 1924, moving the business to Geneva at the end of the war.

Joufroi de Poitiers or Joufrois is a 13th-century French romance in 4613 octosyllabic verses. Only one manuscript of this work is preserved, in the Royal Library, Copenhagen, and this gives the romance in an incomplete form.

Gaston Raynaud was a French philologist and librarian.

The Acre Bible is a partial Old French version of the Old Testament, containing both new and revised translations of 15 canonical and 4 deuterocanonical books, plus a prologue and glosses. The books are Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, 1 and 2 Samuel, 1 and 2 Kings, Judith, Esther, Job, Tobit, Proverbs, 1 and 2 Maccabees and Ruth. It is an early and somewhat rough vernacular translation. Its version of Job is the earliest vernacular translation in Western Europe.