A bicycle, also called a pedal cycle, bike, push-bike or cycle, is a human-powered or motor-assisted, pedal-driven, single-track vehicle, with two wheels attached to a frame, one behind the other. A bicycle rider is called a cyclist, or bicyclist.

Cycling, also known as bicycling or biking, is the activity of riding a bicycle or other type of cycle. It encompasses the use of human-powered vehicles such as balance bikes, unicycles, tricycles, and quadricycles. Cycling is practised around the world for purposes including transport, recreation, exercise, and competitive sport.

Mountain biking is a sport of riding bicycles off-road, often over rough terrain, usually using specially designed mountain bikes. Mountain bikes share similarities with other bikes but incorporate features designed to enhance durability and performance in rough terrain, such as air or coil-sprung shocks used as suspension, larger and wider wheels and tires, stronger frame materials, and mechanically or hydraulically actuated disc brakes. Mountain biking can generally be broken down into distinct categories: cross country, trail, all mountain, enduro, downhill and freeride.

A motorcycle helmet is a type of helmet used by motorcycle riders. Motorcycle helmets contribute to motorcycle safety by protecting the rider's head in the event of an impact. They reduce the risk of head injury by 69% and the risk of death by 42%. Their use is required by law in many countries.

High-visibility clothing, sometimes shortened to hi vis or hi viz, is any clothing worn that is highly luminescent in its natural matt property or a color that is easily discernible from any background. It is most commonly worn on the torso and arm area of the body. Health and safety regulations often require the use of high visibility clothing as it is a form of personal protective equipment. Many colors of high visibility vests are available, with yellow and orange being the most common examples. Colors other than yellow or orange may not provide adequate luminescence for conformity to standards such as ISO 20471.

Utility cycling encompasses any cycling done simply as a means of transport rather than as a sport or leisure activity. It is the original and most common type of cycling in the world. Cycling mobility is one of the various types of private transport and a major part of individual mobility.

Road cycling is the most widespread form of cycling in which cyclists ride on paved roadways. It includes recreational, racing, commuting, and utility cycling. As users of the road, road cyclists are generally expected to obey the same laws as motorists, however there are certain exceptions. While there are many types of bicycles that are used on the roads such as BMX, recumbents, racing, touring and Utility bicycles, dedicated road bicycles have specific characteristics that make them ideal for the sport. Road bicycles have thinner tires, lighter frames with no suspension, and a set of drop handle bars to allow riders to get in a more aerodynamic position while cycling at higher speeds. On a flat road, an intermediate cyclist can average about 18 to 20 mph, while a professional rider can average up to 25 mph (40 km/h). At higher speeds, wind resistance becomes an important factor; aerodynamic road bikes have been developed over the years to ensure that as much as possible of the rider's energy is spent propelling the bike forward.

A bicycle helmet is a type of helmet designed to attenuate impacts to the head of a cyclist in collisions while minimizing side effects such as interference with peripheral vision.

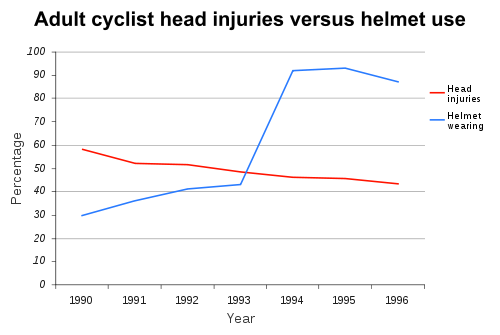

Risk compensation is a theory which suggests that people typically adjust their behavior in response to perceived levels of risk, becoming more careful where they sense greater risk and less careful if they feel more protected. Although usually small in comparison to the fundamental benefits of safety interventions, it may result in a lower net benefit than expected or even higher risks.

Safety in numbers is the hypothesis that, by being part of a large physical group or mass, an individual is less likely to be the victim of a mishap, accident, attack, or other bad event. Some related theories also argue that mass behaviour can reduce accident risks, such as in traffic safety – in this case, the safety effect creates an actual reduction of danger, rather than just a redistribution over a larger group.

Cycling in Melbourne is an important mode of transport, fitness, sport and recreation in many parts of the city. After a period of significant decline through the mid to late 20th century, additional infrastructure investment, changing transport preferences and increasing congestion has resulted in a resurgence in the popularity of cycling for transport. This is assisted by Melbourne's natural characteristics of relatively flat topography and generally mild climate.

Vehicular cycling is the practice of riding bicycles on roads in a manner that is in accordance with the principles for driving in traffic, and in a way that places responsibility for safety on the individual.

Bicycle safety is the use of road traffic safety practices to reduce risk associated with cycling. Risk can be defined as the number of incidents occurring for a given amount of cycling. Some of this subject matter is hotly debated: for example, which types of cycling environment or cycling infrastructure is safest for cyclists. The merits of obeying the traffic laws and using bicycle lighting at night are less controversial. Wearing a bicycle helmet may reduce the chance of head injury in the event of a crash.

A cycle track or cycleway (British) or bikeway, sometimes historically referred to as a sidepath, is a separate route for cycles and not motor vehicles. In some cases cycle tracks are also used by other users such as pedestrians and horse riders. A cycle track can be next to a normal road, and can either be a shared route with pedestrians or be made distinct from both the pavement and general roadway by vertical barriers or elevation differences.

Bicycle helmets have been mandatory for bicycle riders of all ages in New Zealand since January 1994.

Cycling in Australia is a common form of transport, recreation and sport. Many Australians enjoy cycling because it improves their health and reduces road congestion and air pollution. The government has encouraged more people to start, with several state advertising campaigns aimed at increasing safety for those who choose to ride. There is a common perception that riding is a dangerous activity. While it is safer to walk, cycling is a safer method of transport than driving. Cycling is less popular in Australia than in Europe, however cyclists make up one in forty road deaths and one in seven serious injuries.

Australia was the first country to make wearing bicycle helmets mandatory. The majority of early statistical data regarding the effectiveness of bicycle helmets originated from Australia. Their efficacy is still a matter of debate.

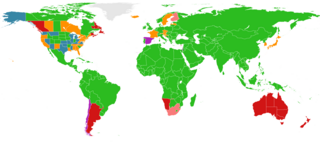

The wearing of bicycle helmets and attitudes towards their use vary around the world. The effects of compulsory use of helmets are disputed. Four countries currently both require and enforce universal use of helmets by cyclists. Partial rules apply in some other jurisdictions, such as only for children, in certain states or sub-national divisions, or under other limited conditions.

The requirement to wear bicycle helmetsin the United States varies by jurisdiction and by age of the cyclist, for example 21 states and the District of Columbia have statewide mandatory helmet laws for children. 29 US states have no statewide law, and 13 of these states have no such laws in any lower-level jurisdiction either.

There is debate over the safety implications of cycling infrastructure. Recent studies generally affirm that segregated cycle tracks have a better safety record between intersections than cycling on major roads in traffic. Furthermore, cycling infrastructure tends to lead to more people cycling. A higher modal share of people cycling is correlated with lower incidences of cyclist fatalities, leading to a "safety in numbers" effect though some contributors caution against this hypothesis. On the contrary, older studies tended to come to negative conclusions about mid-block cycle track safety.