The United States does not have an official language at the federal level, but the most commonly used language is English, which is the de facto national language. In addition, 32 U.S. states out of 50 and all five U.S. territories have declared English as an official language. The great majority of the U.S. population speaks only English at home. The remainder of the population speaks many other languages at home, most notably Spanish, according to the American Community Survey (ACS) of the U.S. Census Bureau; others include indigenous languages originally spoken by Native Americans, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, and native populations in the U.S. unincorporated territories. Other languages were brought in by people from Europe, Africa, Asia, other parts of the Americas, and Oceania, including multiple dialects, creole languages, pidgin languages, and sign languages originating in what is now the United States. Interlingua, an international auxiliary language, was also created in the U.S.

An official language is a language having certain rights to be used in defined situations. These rights can be created in written form or by historic usage.

In linguistics, diglossia is a situation in which two dialects or languages are used by a single language community. In addition to the community's everyday or vernacular language variety, a second, highly codified lect is used in certain situations such as literature, formal education, or other specific settings, but not used normally for ordinary conversation. The H variety may have no native speakers within the community. In cases of three dialects, the term triglossia is used. When referring to two writing systems coexisting for a single language, the term digraphia is used.

The European Union (EU) has 24 official languages, of which three – English, French and German – have the higher status of "procedural" languages of the European Commission. Irish previously had the lower status of "treaty language" before being upgraded to an official and working language in 2007. However, a temporary derogation was enforced until 1 January 2022. The three procedural languages are those used in the day-to-day workings of the institutions of the EU. The designation of Irish as a "treaty language" meant that only the treaties of the European Union were translated into Irish, whereas Legal Acts of the European Union adopted under the treaties did not have to be. Luxembourgish and Turkish, which have official status in Luxembourg and Cyprus, respectively, are the only two official languages of EU member states that are not official languages of the EU. In 2023, the Spanish government requested that its co-official languages Catalan, Basque, and Galician be added to the official languages of the EU.

A multitude of languages have always been spoken in Canada. Prior to Confederation, the territories that would become Canada were home to over 70 distinct languages across 12 or so language families. Today, a majority of those indigenous languages are still spoken; however, most are endangered and only about 0.6% of the Canadian population report an Indigenous language as their mother tongue. Since the establishment of the Canadian state, English and French have been the co-official languages and are, by far, the most-spoken languages in the country.

A minority language is a language spoken by a minority of the population of a territory. Such people are termed linguistic minorities or language minorities. With a total number of 196 sovereign states recognized internationally and an estimated number of roughly 5,000 to 7,000 languages spoken worldwide, the vast majority of languages are minority languages in every country in which they are spoken. Some minority languages are simultaneously also official languages, such as Irish in Ireland or the numerous indigenous languages of Bolivia. Likewise, some national languages are often considered minority languages, insofar as they are the national language of a stateless nation.

A regional language is a language spoken in a region of a sovereign state, whether it be a small area, a federated state or province or some wider area.

The English language in Europe, as a native language, is mainly spoken in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Outside of these states, it has official status in Malta, the Crown Dependencies, Gibraltar and the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia. In the Netherlands, English has an official status as a regional language on the isles of Saba and Sint Eustatius. In other parts of Europe, English is spoken mainly by those who have learnt it as a second language, but also, to a lesser extent, natively by some expatriates from some countries in the English-speaking world.

A pluricentric language or polycentric language is a language with several codified standard forms, often corresponding to different countries. Many examples of such languages can be found worldwide among the most-spoken languages, including but not limited to Chinese in mainland China, Taiwan and Singapore; English in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, South Africa, India, and elsewhere; and French in France, Canada, and elsewhere. The converse case is a monocentric language, which has only one formally standardized version. Examples include Japanese and Russian. In some cases, the different standards of a pluricentric language may be elaborated to appear as separate languages, e.g. Malaysian and Indonesian, Hindi and Urdu, while Serbo-Croatian is in an earlier stage of that process.

A national language is a language that has some connection—de facto or de jure—with a nation. The term is applied quite differently in various contexts. One or more languages spoken as first languages in the territory of a country may be referred to informally or designated in legislation as national languages of the country. National languages are mentioned in over 150 world constitutions.

Official multilingualism is the policy adopted by some states of recognizing multiple languages as official and producing all official documents, and handling all correspondence and official dealings, including court procedure, in these languages. It is distinct from personal multilingualism, the capacity of a person to speak several languages.

Multilingualism is the use of more than one language, either by an individual speaker or by a group of speakers. It is believed that multilingual speakers outnumber monolingual speakers in the world's population. More than half of all Europeans claim to speak at least one language other than their mother tongue; but many read and write in one language. Being multilingual is advantageous for people wanting to participate in trade, globalization and cultural openness. Owing to the ease of access to information facilitated by the Internet, individuals' exposure to multiple languages has become increasingly possible. People who speak several languages are also called polyglots.

Linguistic rights are the human and civil rights concerning the individual and collective right to choose the language or languages for communication in a private or public atmosphere. Other parameters for analyzing linguistic rights include the degree of territoriality, amount of positivity, orientation in terms of assimilation or maintenance, and overtness.

Linguistic discrimination is unfair treatment of people which is based on their use of language and the characteristics of their speech, including their first language, their accent, the perceived size of their vocabulary, their modality, and their syntax. For example, an Occitan speaker in France will probably be treated differently from a French speaker. Based on a difference in use of language, a person may automatically form judgments about another person's wealth, education, social status, character or other traits, which may lead to discrimination.

There are a number of languages in Morocco. De jure, the two official languages are Standard Arabic and Standard Moroccan Berber. Moroccan Arabic is by far the primary spoken vernacular and lingua franca, whereas Berber languages serve as vernaculars for significant portions of the country. The languages of prestige in Morocco are Arabic in its Classical and Modern Standard Forms and sometimes French, the latter of which serves as a second language for approximately 33% of Moroccans. According to a 2000–2002 survey done by Moha Ennaji, author of Multilingualism, Cultural Identity, and Education in Morocco, "there is a general agreement that Standard Arabic, Moroccan Arabic, and Berber are the national languages." Ennaji also concluded "This survey confirms the idea that multilingualism in Morocco is a vivid sociolinguistic phenomenon, which is favored by many people."

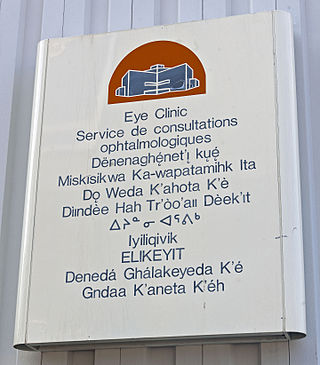

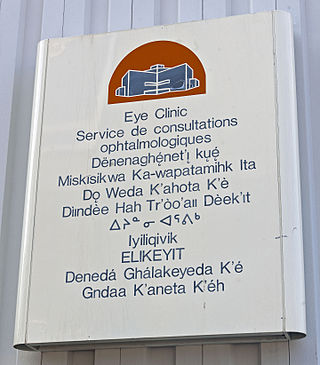

The linguistic landscape refers to the "visibility and salience of languages on public and commercial signs in a given territory or region". Linguistic landscape research has been described as being "somewhere at the junction of sociolinguistics, sociology, social psychology, geography, and media studies". It is a concept which originated in sociolinguistics and language policy as scholars studied how languages are visually displayed and hierarchised in multilingual societies, from large metropolitan centers to Amazonia. For example, linguistic landscape scholars have described how and why some public signs in Jerusalem are presented in Hebrew, English, and Arabic, or a combination thereof. It also looks at how communication in public space plays a crucial role in the organisation of society.

Many countries and national censuses currently enumerate or have previously enumerated their populations by languages, native language, home language, level of knowing language or a combination of these characteristics.

In bilingual education, students are taught content areas like math, science, and history in two languages. Numerous countries or regions have implemented different forms of bilingual education.