The Olmecs were the earliest known major Mesoamerican civilization. Following a progressive development in Soconusco, they occupied the tropical lowlands of the modern-day Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco. It has been speculated that the Olmecs derived in part from the neighboring Mokaya or Mixe–Zoque cultures.

Bonampak is an ancient Maya archaeological site in the Mexican state of Chiapas. The site is approximately 30 km (19 mi) south of the larger site of the people Yaxchilan, under which Bonampak was a dependency, and the border with Guatemala. While the site is not overly spatial or abundant in architectural size, it is well known for the murals located within the three roomed Structure 1. The construction of the site's structures dates to the Late Classic period. The Bonampak murals are noteworthy for being among the best-preserved Maya murals.

Yaxchilan is an ancient Maya city located on the bank of the Usumacinta River in the state of Chiapas, Mexico. In the Late Classic Period Yaxchilan was one of the most powerful Maya states along the course of the Usumacinta River, with Piedras Negras as its major rival. Architectural styles in subordinate sites in the Usumacinta region demonstrate clear differences that mark a clear boundary between the two kingdoms.

The Vision Serpent is an important creature in Pre-Columbian Maya mythology, although the term itself is now slowly becoming outdated.

The calendrical systems devised and used by the pre-Columbian cultures of Mesoamerica, primarily a 260-day year, were used in religious observances and social rituals, such as divination.

Sacrifice was a religious activity in Maya culture, involving the killing of humans or animals, or bloodletting by members of the community, in rituals superintended by priests. Sacrifice has been a feature of almost all pre-modern societies at some stage of their development and for broadly the same reason: to propitiate or fulfill a perceived obligation towards the gods.

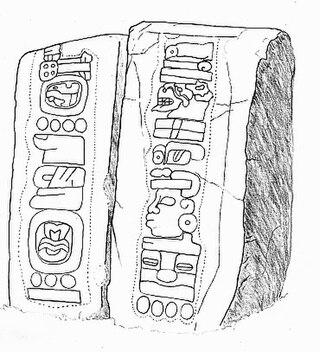

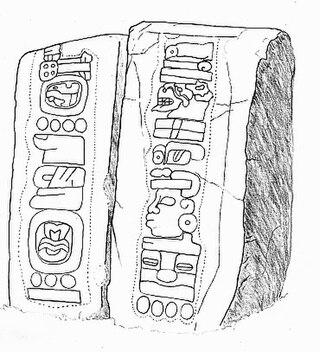

Lintel 24 is the designation given by modern archaeologists to an ancient Maya limestone sculpture from Yaxchilan, in modern Chiapas, Mexico. The lintel dates to about 723–726 AD, placing it within the Maya Late Classic period. Its mid-relief carving depicts the ruler of Yaxchilan, Itzamnaaj Bahlam III, and his consort Lady K’abal Xoc, performing a ceremony of bloodletting; the imagery is also accompanied by descriptive captions, and a signature by the sculptor, Mo’ Chaak.

Maya society concerns the social organization of the Pre-Hispanic Maya, its political structures, and social classes. The Maya people were indigenous to Mexico and Central America and the most dominant people groups of Central America up until the 6th century.

The traditional Maya or Mayan religion of the extant Maya peoples of Guatemala, Belize, western Honduras, and the Tabasco, Chiapas, Quintana Roo, Campeche and Yucatán states of Mexico is part of the wider frame of Mesoamerican religion. As is the case with many other contemporary Mesoamerican religions, it results from centuries of symbiosis with Roman Catholicism. When its pre-Hispanic antecedents are taken into account, however, traditional Maya religion has already existed for more than two and a half millennia as a recognizably distinct phenomenon. Before the advent of Christianity, it was spread over many indigenous kingdoms, all with their own local traditions. Today, it coexists and interacts with pan-Mayan syncretism, the 're-invention of tradition' by the Pan-Maya movement, and Christianity in its various denominations.

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area that begins in the southern part of North America and extends to the Pacific coast of Central America, thus comprising the lands of central and southern Mexico, all of Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, and small parts of Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica. As a cultural area, Mesoamerica is defined by a mosaic of cultural traits developed and shared by its indigenous cultures.

La Mojarra Stela 1 is a Mesoamerican carved monument (stela) dating from 156 CE. It was discovered in 1986, pulled from the Acula River near La Mojarra, Veracruz, Mexico, not far from the Tres Zapotes archaeological site. The 4+1⁄2-foot-wide (1.4 m) by 6+1⁄2-foot-high (2.0 m), four-ton limestone slab contains about 535 glyphs of the Isthmian script. One of Mesoamerica's earliest known written records, this Epi-Olmec culture monument not only recorded this ruler's achievements, but placed them within a cosmological framework of calendars and astronomical events.

Mesoamerica, along with Mesopotamia and China, is one of three known places in the world where writing is thought to have developed independently. Mesoamerican scripts deciphered to date are a combination of logographic and syllabic systems. They are often called hieroglyphs due to the iconic shapes of many of the glyphs, a pattern superficially similar to Egyptian hieroglyphs. Fifteen distinct writing systems have been identified in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, many from a single inscription. The limits of archaeological dating methods make it difficult to establish which was the earliest and hence the progenitor from which the others developed. The best documented and deciphered Mesoamerican writing system, and the most widely known, is the classic Maya script. Earlier scripts with poorer and varying levels of decipherment include the Olmec hieroglyphs, the Zapotec script, and the Isthmian script, all of which date back to the 1st millennium BC. An extensive Mesoamerican literature has been conserved, partly in indigenous scripts and partly in postconquest transcriptions in the Latin script.

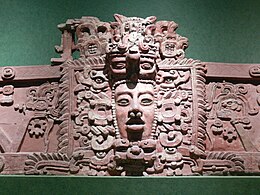

Ancient Maya art comprises the visual arts of the Maya civilization, an eastern and south-eastern Mesoamerican culture made up of a great number of small kingdoms in present-day Mexico, Guatemala, Belize and Honduras. Many regional artistic traditions existed side by side, usually coinciding with the changing boundaries of Maya polities. This civilization took shape in the course of the later Preclassic Period, when the first cities and monumental architecture started to develop and the hieroglyphic script came into being. Its greatest artistic flowering occurred during the seven centuries of the Classic Period.

Lady Kʼabʼal Xook or Lady Xoc, was a Maya Queen consort of Yaxchilan. She was the principal wife and aunt of King Itzamnaaj Bahlam III, who ruled the prominent kingdom of Yaxchilan from 681 to 742. She is believed by many to have been the sister of Lady Pacal.

The pre-Columbian Maya religion knew various jaguar gods, in addition to jaguar demi-gods, (ancestral) protectors, and transformers. The main jaguar deities are discussed below. Their associated narratives are still largely to be reconstructed. Lacandon and Tzotzil-Tzeltal oral tradition are particularly rich in jaguar lore.

The Epi-Olmec culture was a cultural area in the central region of the present-day Mexican state of Veracruz. Concentrated in the Papaloapan River basin, a culture that existed during the Late Formative period, from roughly 300 BCE to roughly 250 CE. Epi-Olmec was a successor culture to the Olmec, hence the prefix "epi-" or "post-". Although Epi-Olmec did not attain the far-reaching achievements of that earlier culture, it did realize, with its sophisticated calendrics and writing system, a level of cultural complexity unknown to the Olmecs.

Olmec hieroglyphs designate a possible system of writing or proto-writing developed within the Olmec culture. The Olmecs were the earliest known major Mesoamerican civilization, flourishing during the formative period in the tropical lowlands of the modern-day Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco. The subsequent Epi-Olmec culture, was a successor culture to the Olmec and featured a full-fledged writing system, the Isthmian script.

The use of mirrors in Mesoamerican culture was associated with the idea that they served as portals to a realm that could be seen but not interacted with. Mirrors in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica were fashioned from stone and served a number of uses, from the decorative to the divinatory. An ancient tradition among many Mesoamerican cultures was the practice of divination using the surface of a bowl of water as a mirror. At the time of the Spanish conquest this form of divination was still practiced among the Maya, Aztecs and Purépecha. In Mesoamerican art, mirrors are frequently associated with pools of liquid; this liquid was likely to have been water.

During the pre-Columbian era, human sacrifice in Maya culture was the ritual offering of nourishment to the gods and goddesses. Blood was viewed as a potent source of nourishment for the Maya deities, and the sacrifice of a living creature was a powerful blood offering. By extension, the sacrifice of human life was the ultimate offering of blood to the gods, and the most important Maya rituals culminated in human sacrifice. Generally, only high-status prisoners of war were sacrificed, and lower status captives were used for labor.

The Classic Maya used dedication rituals to sanctify their living spaces and family members by associating their physical world with supernatural concepts through religious practice. The existence of such rituals is inferred from the frequent occurrence of so-called 'dedication' or 'votive' cache deposits in an archaeological context.