Related Research Articles

Lucy Eldine Gonzalez Parsons was an American labor organizer, radical socialist and anarcho-communist. She is remembered as a powerful orator. Parsons entered the radical movement following her marriage to newspaper editor Albert Parsons and moved with him from Texas to Chicago, where she contributed to the newspaper he famously edited, The Alarm.

Sam Dolgoff (1902–1990) was an anarchist and anarcho-syndicalist from Russia who grew up and lived and was active in the United States.

Grigori Petrovitch Maximoff (1893–1950) was a Russian-born anarcho-syndicalist. In the 1917 Russian Revolution, he wrote for Golos Truda. In 1922, he moved to Berlin and co-founded the Anarcho-Syndicalist International. After a brief stay in Paris, he moved to the Chicago, where he hung wallpaper and edited Delo Truda. He is interred in Waldheim Cemetery near other Chicago anarchists.

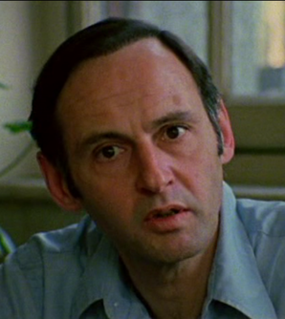

Paul Avrich was a historian of the 19th and early 20th century anarchist movement in Russia and the United States. He taught at Queens College, City University of New York, for his entire career, from 1961 to his retirement as distinguished professor of history in 1999. He wrote ten books, mostly about anarchism, including topics such as the 1886 Haymarket Riot, 1921 Sacco and Vanzetti case, 1921 Kronstadt naval base rebellion, and an oral history of the movement.

Vsevolod Mikhailovich Eikhenbaum, known later as Volin or Voline (Во́лин), was a Russian anarchist who participated in the Russian and Ukrainian Revolutions before being forced into exile by the Bolshevik Party. He was a proponent of the anarchist organizational form known as synthesis anarchism.

Fanya Anisimovna Baron (1887–1921) was a Lithuanian Jewish anarchist revolutionary. She spent her early life participating in the Chicago workers' movement, but following the 1917 Revolution, she moved to Ukraine and participated in the Makhnovist movement. For her anarchist activities, she was arrested and executed by the Cheka.

Anarchism in the United States began in the mid-19th century and started to grow in influence as it entered the American labor movements, growing an anarcho-communist current as well as gaining notoriety for violent propaganda of the deed and campaigning for diverse social reforms in the early 20th century. By around the start of the 20th century, the heyday of individualist anarchism had passed and anarcho-communism and other social anarchist currents emerged as the dominant anarchist tendency. Social anarchists, like Emma Goldman, can be credited with the introduction of LGBTQ social movements to the United States.

Anarchism in Russia has its roots in the early mutual aid systems of the medieval republics and later in the popular resistance to the Tsarist autocracy and serfdom. Through the history of radicalism during the early 19th-century, anarchism developed out of the populist and nihilist movements' dissatisfaction with the government reforms of the time.

Labour's Cause or The Cause of Labour was an anarchist and platformist journal first published 1925.

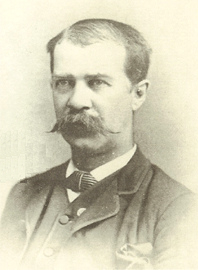

Dyer Daniel Lum was an American anarchist, labor activist and poet. A leading syndicalist and a prominent left-wing intellectual of the 1880s, Lum is best remembered as the lover and mentor of early anarcha-feminist Voltairine de Cleyre.

Free Society was a major anarchist newspaper in the United States at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. Most anarchist publications in the US were in Yiddish, German, or Russian, but Free Society was published in English, permitting the dissemination of anarchist thought to English-speaking populations in the US.

Louise Berger was a Russian Latvian anarchist, a member of the Anarchist Red Cross, and editor of Emma Goldman's Mother Earth Bulletin in New York. Berger became well known outside anarchist circles in 1914 after a premature bomb explosion at her New York City apartment, which killed four persons and destroyed part of the building.

Alexander "Sanya" Moiseyevich Schapiro or Shapiro was a Russian anarcho-syndicalist activist. Born in southern Russia, Schapiro left Russia at an early age and spent most of his early activist years in London.

Golos Truda was a Russian-language anarchist newspaper. Founded by working-class Russian expatriates in New York City in 1911, Golos Truda shifted to Petrograd during the Russian Revolution in 1917, when its editors took advantage of the general amnesty and right of return for political dissidents. There, the paper integrated itself into the anarchist labour movement, pronounced the necessity of a social revolution of and by the workers, and situated itself in opposition to the myriad of other left-wing movements.

Maksim Rayevsky was a Russian-Jewish anarcho-syndicalist.

Olga Ilyichnina Taratuta was a Ukrainian anarcho-communist. She was the founder of the Ukrainian Anarchist Black Cross.

The Haymarket affair, also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, the Haymarket Square riot, or the Haymarket Incident, was the aftermath of a bombing that took place at a labor demonstration on May 4, 1886, at Haymarket Square in Chicago, Illinois, United States. It began as a peaceful rally in support of workers striking for an eight-hour work day, the day after the events at the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company, during which one person was killed and many workers injured. An unknown person threw a dynamite bomb at the police as they acted to disperse the meeting, and the bomb blast and ensuing gunfire resulted in the deaths of seven police officers and at least four civilians; dozens of others were wounded.

Freie Arbeiter Stimme was a Yiddish-language anarchist newspaper published from New York City's Lower East Side between 1890 and 1977. It was among the world's longest running anarchist journals, and the primary organ of the Jewish anarchist movement in the United States; at the time that it ceased publication it was the world's oldest Yiddish newspaper. Historian of anarchism Paul Avrich described the paper as playing a vital role in Jewish–American labor history and upholding a high literary standard, having published the most lauded writers and poets in Yiddish radicalism. The paper's editors were major figures in the Jewish–American anarchist movement: David Edelstadt, Saul Yanovsky, Joseph Cohen, Hillel Solotaroff, Roman Lewis, and Moshe Katz.

The Chicago idea is an ideology combining anarchism and revolutionary unionism. It was a precursor to anarcho-syndicalism professed by Chicago anarchists, especially Albert Parsons and August Spies, in the mid-1880s.

The Congress of Socialists of the United States, better known as the 1881 Chicago Social Revolutionary Congress, was a meeting of anarchists and socialists in Chicago in October 1881 to organize the new social revolutionary groups splintered from the American Socialistic Labor Party.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Boris Yelensky". International Institute on Social History. International Institute on Social History. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- 1 2 "Cemetery Inhabitants". Illinois Labor History Society. Illinois Labor History Society. Archived from the original on 19 May 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- 1 2 Zimmer, Kenyon. "Premature Anti-Communists?: American Anarchism, the Russian Revolution, and Left-Wing Libertarian Anti-Communism, 1917-1939."Labor 6.2 (2009): 45-71.

- ↑ Walter, Nicolas. "Anarchism in Print: yesterday and today." Government and Opposition 5.4 (1970): 523-540.

- 1 2 3 "Yelensky, Boris". IATH, University of Virginia. IATH, University of Virginia. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "YELENSKY, Boris". Dictionnaire des militants anarchistes. Dictionnaire des militants anarchistes. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ↑ Allan Antliff (30 November 2007). Anarchist Modernism: Art, Politics, and the First American Avant-Garde. University of Chicago Press. pp. 254–. ISBN 978-0-226-02104-1.

- ↑ Boscà, Martí, José Vicente, and Antonio Rey González. "El viaje de Félix Martí Ibáñez a Norteamérica en busca de apoyos internacionales. Agosto–diciembre, 1938."

- ↑ Goldman, Emma. Vision on Fire: Emma Goldman on the Spanish Revolution. AK Press, 2006.

- ↑ Carolyn Ashbaugh (5 February 2013). Lucy Parsons: An American Revolutionary. Haymarket Books. pp. 16–. ISBN 978-1-60846-213-1.

- ↑ Maximoff, Gregori Petrovich. Syndicalists in the Russian Revolution. South London DAM-IWA, 1985.

- ↑ Maximoff, Grigorii Petrovich. "The guillotine at work." Twenty Years Terror in Russia (1940).

- ↑ Yelensky, Boris. Boris Yelensky papers, 1939-1975. World Cat. OCLC 66895331.

- ↑ Yelensky, Boris. "In the Struggle for Equality." (1958).

- ↑ Paul Avrich (2005). Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America. AK Press. pp. 523–. ISBN 978-1-904859-27-7.