Africa has the longest record of human habitation in the world. The first hominins emerged 6-7 million years ago, and among the earliest anatomically modern human skulls found so far were discovered at Omo Kibish, Jebel Irhoud, and Florisbad.

The ruins of Gedi are a historical and archaeological site near the Indian Ocean coast of eastern Kenya. The site is adjacent to the town of Gedi in the Kilifi District and within the Arabuko-Sokoke Forest.

The Kingdom of Mapungubwe was a medieval state in South Africa located at the confluence of the Shashe and Limpopo rivers, south of Great Zimbabwe. The name is derived from either TjiKalanga and Tshivenda. The name might mean "Hill of Jackals" or "stone monuments". The kingdom was the first stage in a development that would culminate in the creation of the Kingdom of Zimbabwe in the 13th century, and with gold trading links to Rhapta and Kilwa Kisiwani on the African east coast. The Kingdom of Mapungubwe lasted about 80 years, and at its height the capital's population was about 5000 people.

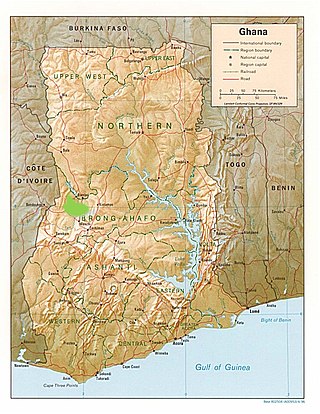

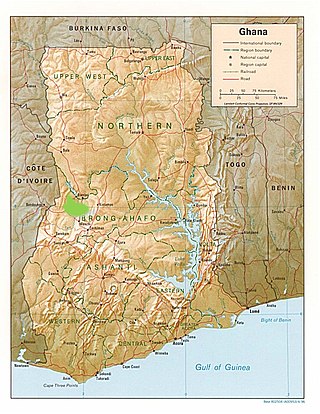

The Kintampo complex, also known as the Kintampo culture, Kintampo Neolithic, and Kintampo Tradition, was established by Saharan agropastoralists, who may have been Niger-Congo or Nilo-Saharan speakers and were distinct from the earlier residing Punpun foragers, between 2500 BCE and 1400 BCE. The Kintampo complex was a part of a transitory period in the prehistory of West Africa, from pastoralism to sedentism in West Africa, specifically in the Bono East region of Ghana, eastern Ivory Coast, and Togo. The Kintampo complex also featured art, personal adornment items, polished stone beads, bracelets, and figurines; additionally, stone tools and structures were found, which suggests that Kintampo people had both a complex society and were skilled with Later Stone Age technologies.

The Mapungubwe Collection at the University of Pretoria Museums comprises archaeological material excavated by the University of Gauteng at the Mapungubwe archaeological site since its discovery in 1933. The archaeological collection comprises ceramics, metals, trade glass beads, indigenous beads, clay figurines, and bone and ivory artefacts as well as an extensive research collection of potsherds, faunal remains and other fragmentary material. The University of Gauteng established a permanent museum in June 2000, thereby making the archaeological collection more widely available for public access and interest beyond the confines of academia. The collection is kept on site for tourism purposes.

The Tsodilo Hills are a UNESCO World Heritage Site (WHS), consisting of rock art, rock shelters, depressions, and caves in southern Africa. It gained its WHS listing in 2001 because of its unique religious and spiritual significance to local peoples, as well as its unique record of human settlement over many millennia. UNESCO estimates there are over 4500 rock paintings at the site. The site consists of a few main hills known as the Child Hill, Female Hill, and Male Hill.

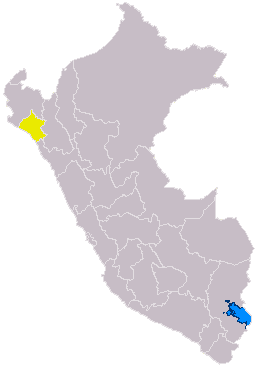

The Sican culture is the name that archaeologist Izumi Shimada gave to the culture that inhabited what is now the north coast of Peru between about 750 and 1375 CE. According to Shimada, Sican means "temple of the Moon". The Sican culture is also referred to as Lambayeque culture, after the name of the region in Peru. It succeeded the Moche culture. There is still controversy among archeologists and anthropologists over whether the two are separate cultures. The Sican culture is divided into three major periods based on cultural changes as evidenced in archeological artifacts.

Ing'ombe Ilede is an archaeological site located on a hill near the confluence of the Zambezi and Lusitu rivers, near the town of Siavonga, in Zambia. Ing'ombe Ilede, meaning "a sleeping cow", received its name from a local baobab tree that is partially lying on the ground and resembles a sleeping cow from a distance. The site is thought to have been a small commercial state around the 16th century whose chief item of trade was salt. Ing'ombe Ilede received various goods from the hinterland of south-central Africa, such as, copper, slaves, gold and ivory. These items were exchanged with glass beads, cloth, cowrie shells from the Indian Ocean trade. The status of Ing'ombe Ilede as a trading center that connected different places in south-central Africa has made it a very important archaeological site in the region.

Chibuene is a Mozambican archaeological site, located five kilometres south of the coastal city of Vilanculos South Beach. The site was occupied during two distinct phases. The earlier phase of occupation dates to the late first millennium AD. The second phase dates from around 1450 and is contemporaneous with the Great Zimbabwe civilization in the African interior. During both phases of its development Chibuene was a trading settlement. Trade goods obtained from the site include glass beads, painted blue and white ceramics, and glass bottle fragments. The later phase of settlement has yielded remains of medieval structures as well as evidence of metallurgy. Crucibles have been found that were presumably used to melt gold obtained from trade with the Great Zimbabwe civilization. There is evidence that Chibuene traded extensively with the inland settlement of Manyikeni. Mozambique has jointly inscribed these two properties on their tentative version of the World Heritage List.

Enkapune Ya Muto, also known as Twilight Cave, is a site spanning the late Middle Stone Age to the Late Stone Age on the Mau Escarpment of Kenya. This time span has allowed for further study of the transition from the Middle Stone Age to the Late Stone Age. In particular, the changes in lithic and pottery industries can be tracked over these time periods as well as transitions from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a herding lifestyle. Beads made of perforated ostrich egg shells found at the site have been dated to 40,000 years ago. The beads found at the site represent the early human use of personal ornaments. Inferences pertaining to climate and environment changes during the pre-Holocene and Holocene period have been made based from faunal remains based in this site.

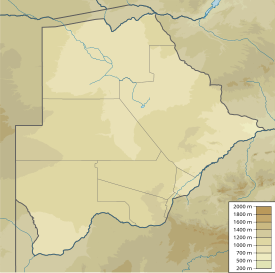

Toutswemogala Hill lies 6.5 km West of the North-South Highway in the Central District of Botswana. It is situated about 50 km north of the village of Palapye. Toutswemogala is an elongated flat-topped hill, geologically called a mesa, rising about 50 meters above the surrounding flat mopane veld. It is an Iron Age settlement, which has been occupied on two occasions. The radio-carbon dates for this settlement range from 7th to late 19th century AD indicating occupation of more than one thousand years. The hill was part of the formation of early states in Southern Africa with cattle keeping as major source of economy. This was supplemented by goats, sheep and foraging as well as hunting of wild animals. The remaining features of Toutswe settlement include house-floors, large heaps of vitrified cow-dung and burials while the outstanding structure is the stone wall. There are large traits of centaurs ciliaris, a type of grass which has come to be associated with cattle-keeping settlements in South, Central Africa.

Pampa Grande is an archaeological site located in the Lambayeque Valley, in northern Peru, situated on the south shore of the Chancay River. It is located to the east of the city of Chiclayo.

Leopard's Kopje is an archaeological site, the type site of the associated region or culture that marked the Middle Iron Age in Zimbabwe. The ceramics from the Leopard's Kopje type site have been classified as part of phase II of the Leopard's Kopje culture. For information on the region of Leopard's Kopje, see the "Associated sites" section of this article.

Banda District in Ghana plays an important role in the understanding of trade networks and the way they shaped the lives of people living in western Africa. Banda District is located in West Central Ghana, just south of the Black Volta River in a savanna woodland environment. This region has many connections to trans-Saharan trade, as well as Atlantic trade and British colonial and economic interests. The effects of these interactions can be seen archaeologically through the presence of exotic goods and export of local materials, production of pottery and metals, as well as changes in lifestyle and subsistence patterns. Pioneering archaeological research in this area was conducted by Ann Stahl.

Pemba Island is a large coral island off the coast of Tanzania. Inhabited by Bantu settlers from the Tanga coast since 600 AD, the island has a rich trading, agricultural, and religious history that has contributed to the studies of the Swahili Coast trade throughout the Indian Ocean.

R12 is a middle Neolithic cemetery located in the Northern Dongola Reach on the banks of the Seleim Nile palaeochannel of modern-day Sudan. The site is dated to between 5000 and 4000 BC. Centro Veneto di Studi Classici e Orientali excavated the site, within the concession of the Sudan Archaeological Research Society and after an agreement with it, between 2000 and 2003 over three digging seasons. The first was in 2000 and 33 graves were discovered. The second was in 2001 and another 33 graves were discovered. The third was in 2003 and the last 100 graves were discovered. There are 166 graves total at the site. Contents of the graves include ceramics, animal bones, grinding stones, human skeletons, and plant remains.

Kweneng’ ruins are the remains of a pre-colonial Tswana capital occupied from the 15th to the 19th century AD in South Africa. The site is located 30km south of the modern-day city of Johannesburg. Settlement at the site likely began around the 1400s and saw its peak in the 15th century. The Kweneng' ruins are similar to those built by other early civilizations found in the southern Africa region during this period, including the Luba–Lunda kingdom, Kingdom of Mutapa, Bokoni, and many others, as these groups share ancestry. Kweneng' was the largest of several sizable settlements inhabited by Tswana speakers prior to European arrival. Several circular stone walled family compounds are spread out over an area 10km long and 2km wide. It is likely that Kweneng' was abandoned in the 1820s during the period of colonial expansion-related civil wars known as the Mfecane or Difaqane, leading to the dispersal of its inhabitants.

Kissi is an Burkinabe archaeological site located in the Oudalan Province of Burkina Faso, near the lake Mare de Kissi and near the borders of Mali, Niger, and the Niger River. Occupied during the Iron Age, Kissi provides evidence for Iron Age textiles, beads, and mortuary practices. The site also has unique ceramic and settlement sequences to it, with clusters of mounds located throughout the site. Radiocarbon dating dates the specific occupation of the site from 1000 BC to 1300 AD.

Ghaba is a Neolithic cemetery mound and African archaeological site located in Central Sudan in the Shendi region of the Nile Valley. The site, discovered in 1977 by the Section Française de la Direction des Antiquités du Soudan (SFDAS) while they were investigating nearby Kadada, dates to 4750–4350 and 4000–3650 cal BC. Archaeology of the site originally heavily emphasized pottery, as there were many intact or mostly intact vessels. Recent analysis has focused on study of plant material found, which indicates that Ghaba may have been domesticating cereals earlier than previously believed. Though the site is a cemetery, little analysis has taken place on the skeletons due to circumstances of the excavation and poor preservation due to the environment. The artifacts at Ghaba suggest the people who used the cemetery were part of a regionalization separating central Sudan's Neolithic from Nubia. While many traditions match with Nubia, the people represented at Ghaba had some of their own particular practices in food production and bead and pottery production, which likely occurred on a relatively small scale. They also had some distinct funerary traditions, as evidenced by their grave goods. The people at Ghaba would have likely existed at least partially in a trade network that spread through the Nile and to the Red Sea. They used agriculture, cultivation, and cattle for sustenance.

Daima is a mound settlement located in Nigeria, near Lake Chad, and about 5 kilometers away from the Nigerian frontier with Cameroon. It was first excavated in 1965 by British archaeologist Graham Connah. Radiocarbon dating showed the occupations at Daima cover a period beginning early in the first millennium BC, and ending early in the second millennium AD. The Daima sequence then covers some 1800 years. Daima is a perfect example of an archaeological tell site, as Daima’s stratigraphy seems to be divided into three periods or phases which mark separate occupations. These phases are called Daima I, Daima II, and Daima III. Although these occupations differ from each other in multiple ways, they also have some shared aspects with one another. Daima I represents an occupation of a people without metalwork; Daima II is characterized by the first iron-using people of the site; and Daima III represents a rich society with a much more complex material culture.