The Korean War was fought between North Korea and South Korea from 1950 to 1953. It began on 25 June 1950 when North Korea invaded South Korea and ceased after an armistice on 27 July 1953. North Korea was supported by China and the Soviet Union while South Korea was supported by the United States and US-led United Nations (UN) forces.

The history of North Korea began with the end of World War II in 1945. The surrender of Japan led to the division of Korea at the 38th parallel, with the Soviet Union occupying the north, and the United States occupying the south. The Soviet Union and the United States failed to agree on a way to unify the country, and in 1948, they established two separate governments – the Soviet-aligned Democratic People's Republic of Korea and the American-aligned Republic of Korea – each claiming to be the legitimate government of all of Korea.

The history of South Korea begins with the Japanese surrender on 2 September 1945. At that time, South Korea and North Korea were divided, despite being the same people and on the same peninsula. In 1950, the Korean War broke out. North Korea overran South Korea until US-led UN forces intervened. At the end of the war in 1953, the border between South and North remained largely similar. Tensions between the two sides continued. South Korea alternated between dictatorship and liberal democracy. It underwent substantial economic development.

The Lower Paleolithic era on the Korean Peninsula and in Manchuria began roughly half a million years ago. The earliest known Korean pottery dates to around 8000 BC, and the Neolithic period began after 6000 BC, followed by the Bronze Age by 2000 BC, and the Iron Age around 700 BC. Similarly, according to The History of Korea, the Paleolithic people are not the direct ancestors of the present Korean people, but their direct ancestors are estimated to be the Neolithic People of about 2000 BC.

Juche, officially the Juche idea, is the state ideology of North Korea and the official ideology of the Workers' Party of Korea. North Korean sources attribute its conceptualization to Kim Il Sung, the country's founder and first leader. Juche was originally regarded as a variant of Marxism–Leninism until Kim Jong Il, Kim Il Sung's son and successor, declared it a distinct ideology in the 1970s. Kim Jong Il further developed Juche in the 1980s and 1990s by making ideological breaks from Marxism–Leninism and increasing the importance of his father's ideas.

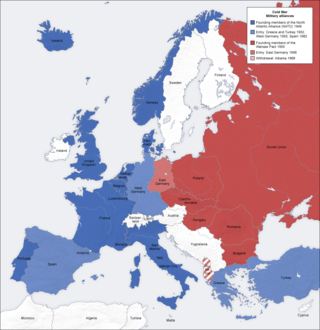

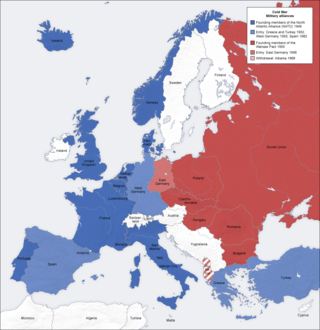

The Korean conflict is an ongoing conflict based on the division of Korea between North Korea and South Korea, both of which claim to be the sole legitimate government of all of Korea. During the Cold War, North Korea was backed by the Soviet Union, China, and other allies, while South Korea was backed by the United States, United Kingdom, and other Western allies.

The division of Korea began on August 15, 1945 when the official announcement of the surrender of Japan was released, thus ending the Pacific Theater of World War II. During the war, the Allied leaders had already been considering the question of Korea's future following Japan's eventual surrender in the war. The leaders reached an understanding that Korea would be liberated from Japan but would be placed under an international trusteeship until the Koreans would be deemed ready for self-rule. In the last days of the war, the United States proposed dividing the Korean peninsula into two occupation zones with the 38th parallel as the dividing line. The Soviets accepted their proposal and agreed to divide Korea.

Area studies, also known as regional studies, are interdisciplinary fields of research and scholarship pertaining to particular geographical, national/federal, or cultural regions. The term exists primarily as a general description for what are, in the practice of scholarship, many heterogeneous fields of research, encompassing both the social sciences and the humanities. Typical area study programs involve international relations, strategic studies, history, political science, political economy, cultural studies, languages, geography, literature, and other related disciplines. In contrast to cultural studies, area studies often include diaspora and emigration from the area.

Minjung is a Korean word that combines the two hanja characters min (民) and jung (衆). Min is from inmin, which may be translated as "the people", and jung is from daejung, which may be translated as "the public". Thus, minjung can be translated to mean "the masses" or "the people."

The United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK) was the official ruling body of the Southern half of the Korean Peninsula from 8 September 1945 to 15 August 1948.

Constitutional Assembly elections were held in South Korea on 10 May 1948. They were held under the U.S. military occupation, with supervision from the United Nations, and resulted in a victory for the National Association for the Rapid Realisation of Korean Independence, which won 55 of the 200 seats, although 85 were held by independents. Voter turnout was 95%.

Jon Halliday is an Irish historian specialising in modern Asia. He was formerly a Senior Visiting Research Fellow at King's College London. He was educated at University of Oxford and has been married to Jung Chang since 1991. Halliday is the older brother of the late Irish International relations academic and writer Fred Halliday.

For over 15 centuries, the relationship between Japan and Korea was characterized by cultural exchanges, economic trade, political contact and military confrontations, all of which underlie their relations even today. During the ancient era, exchanges of cultures and ideas between Japan and mainland Asia were common through migration via the Korean Peninsula, and diplomatic contact and trade between the two.

Meredith Jung-En Woo is an American academic and author. She is a Senior Fellow at the University Design Institute and a Professor of Practice at the School of Politics and Global Studies, both at Arizona State University. She served as President of Sweet Briar College and as the Dean of the College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Virginia. She is the former director of the International Higher Education Support Program at the Open Society Foundations in London.

This is an English language bibliography of scholarly books and articles on the Cold War. Because of the extent of the Cold War, the conflict is well documented.

Donald Kirk is a veteran correspondent and author on conflict and crisis from Southeast Asia to the Middle East to Northeast Asia. Kirk has covered wars from Vietnam to Iraq, focusing on political, diplomatic, economic and social as well as military issues. He is also known for his reporting on North Korea, including the nuclear crisis, human rights and payoffs from South to North Korea preceding the June 2000 inter-Korean summit.[1]

Charles King Armstrong is an American historian of North Korea. From 2005 to 2020, he worked as the Korea Foundation Professor of Korean Studies at Columbia University, spending his last year on sabbatical after the university's determination that he had committed extensive plagiarism. Armstrong's works dealt with revolutions, cultures of socialism, architectural history, and diplomatic history in the contexts of East Asia and modern Korea, with a focus on North Korea.

Korean nationalist historiography is a way of writing Korean history that centers on the Korean minjok, an ethnically defined Korean nation. This kind of nationalist historiography emerged in the early twentieth century among Korean intellectuals who wanted to foster national consciousness to achieve Korean independence from Japanese domination. Its first proponent was journalist and independence activist Shin Chaeho (1880–1936). In his polemical New Reading of History, which was published in 1908 three years after Korea became a Japanese protectorate, Shin proclaimed that Korean history was the history of the Korean minjok, a distinct race descended from the god Dangun that had once controlled not only the Korean peninsula but also large parts of Manchuria. Nationalist historians made expansive claims to the territory of these ancient Korean kingdoms, by which the present state of the minjok was to be judged.

This is a list of works important to the study of North Korea.