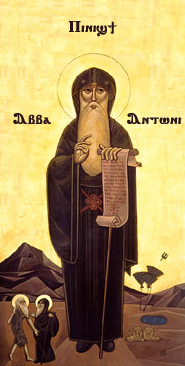

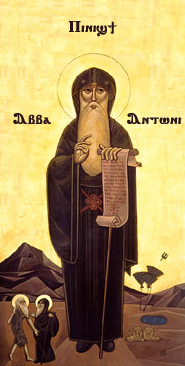

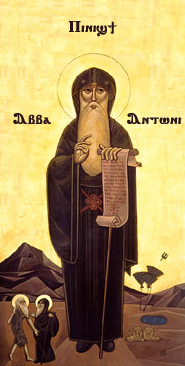

Anthony the Great was a Christian monk from Egypt, revered since his death as a saint. He is distinguished from other saints named Anthony, such as Anthony of Padua, by various epithets: Anthony of Egypt, Anthony the Abbot, Anthony of the Desert, Anthony the Anchorite, Anthony the Hermit, and Anthony of Thebes. For his importance among the Desert Fathers and to all later Christian monasticism, he is also known as the Father of All Monks. His feast day is celebrated on 17 January among the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic churches and on Tobi 22 in the Coptic calendar.

Monasticism, also called monachism or monkhood, is a religious way of life in which one renounces worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual work. Monastic life plays an important role in many Christian churches, especially in the Catholic, Orthodox and Anglican traditions as well as in other faiths such as Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism. In other religions, monasticism is criticized and not practiced, as in Islam and Zoroastrianism, or plays a marginal role, as in modern Judaism.

Pachomius, also known as Saint Pachomius the Great, is generally recognized as the founder of Christian cenobitic monasticism. Coptic churches celebrate his feast day on 9 May, and Eastern Orthodox and Catholic churches mark his feast on 15 May or 28 May. In Lutheranism, he is remembered as a renewer of the church, along with his contemporary, Anthony of Egypt on 17 January.

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which may be a chapel, church, or temple, and may also serve as an oratory, or in the case of communities anything from a single building housing only one senior and two or three junior monks or nuns, to vast complexes and estates housing tens or hundreds. A monastery complex typically comprises a number of buildings which include a church, dormitory, cloister, refectory, library, balneary and infirmary, and outlying granges. Depending on the location, the monastic order and the occupation of its inhabitants, the complex may also include a wide range of buildings that facilitate self-sufficiency and service to the community. These may include a hospice, a school, and a range of agricultural and manufacturing buildings such as a barn, a forge, or a brewery.

A hermit, also known as an eremite or solitary, is a person who lives in seclusion. Eremitism plays a role in a variety of religions.

Christian monasticism is the devotional practice of Christians who live ascetic and typically cloistered lives that are dedicated to Christian worship. It began to develop early in the history of the Christian Church, modeled upon scriptural examples and ideals, including those in the Old Testament. It has come to be regulated by religious rules and, in modern times, the Canon law of the respective Christian denominations that have forms of monastic living. Those living the monastic life are known by the generic terms monks (men) and nuns (women). The word monk originated from the Greek μοναχός, itself from μόνος meaning 'alone'.

The Therapeutae were a Jewish sect which existed in Alexandria and other parts of the ancient Greek world. The primary source concerning the Therapeutae is the De vita contemplativa, traditionally ascribed to the Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria. The author appears to have been personally acquainted with them. The author describes the Therapeutae as "philosophers" and mentions a group that lived on a low hill by the Lake Mareotis close to Alexandria in circumstances resembling lavrite life. They were "the best" of a kind given to "perfect goodness" that "exists in many places in the inhabited world". The author was unsure of the origin of the name and derives the name Therapeutae/Therapeutides from Greek θεραπεύω in the sense of "cure" or "worship".

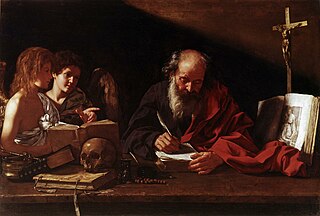

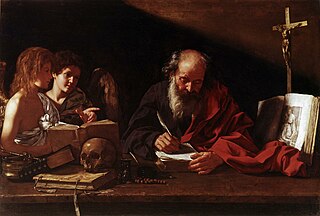

The Desert Fathers were early Christian hermits and ascetics, who lived primarily in the Scetes desert of the Roman province of Egypt, beginning around the third century AD. The Apophthegmata Patrum is a collection of the wisdom of some of the early desert monks and nuns, in print as Sayings of the Desert Fathers. The first Desert Father was Paul of Thebes, and the most well known was Anthony the Great, who moved to the desert in AD 270–271 and became known as both the father and founder of desert monasticism. By the time Anthony had died in AD 356, thousands of monks and nuns had been drawn to living in the desert following Anthony's example, leading his biographer, Athanasius of Alexandria, to write that "the desert had become a city." The Desert Fathers had a major influence on the development of Christianity.

Evagrius Ponticus, also called Evagrius the Solitary, was a Christian monk and ascetic from Heraclea, a city on the coast of Bithynia in Asia Minor. One of the most influential theologians in the late fourth-century church, he was well known as a thinker, polished speaker, and gifted writer. He left a promising ecclesiastical career in Constantinople and traveled to Jerusalem, where in 383 AD he became a monk at the monastery of Rufinus and Melania the Elder. He then went to Egypt and spent the remaining years of his life in Nitria and Kellia, marked by years of asceticism and writing. He was a disciple of several influential contemporary church leaders, including Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nazianzus, and Macarius of Egypt. He was a teacher of others, including John Cassian and Palladius of Galatia.

A skete is a monastic community in Eastern Christianity that allows relative isolation for monks, but also allows for communal services and the safety of shared resources and protection. It is one of four types of early monastic orders, along with the eremitic, lavritic and coenobitic, that became popular during the early formation of the Christian Church.

Tabenna is a Christian community founded in Upper Egypt around 320 by Saint Pachomius. It was the motherhouse of a network which, at his death in 346, already had nine establishments for men and two for women in the same region, with two or three thousand "Tabennesites". Considered the first major model of cenobitic monasticism in the Christian Church.

Eastern Christian monasticism is the life followed by monks and nuns of the Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Church of the East and Eastern Catholicism. Eastern monasticism is founded on the Rule of St Basil and is sometimes thus referred to as Basilian.

Saint Isidora, or Saint Isidore, was a Christian nun and saint of the 4th century AD. She is considered among the earliest fools for Christ. While very little is known of Isidora's life, she is remembered for her exemplification of the writing of St. Paul that “Whosoever of you believes that he is wise by the measure of this world, may he become a fool, so as to become truly wise.” The story of Isidora effectively highlights the Christian ideal that recognition or glory from man is second to one's actions being seen by God, even if that means one's actions or even one's self remains unknown or misunderstood. This ideal was extremely important to the early Desert Fathers and Mothers who recorded Isidora's story.

Coptic monasticism was a movement in the Coptic Orthodox Church to create a holy, separate class of person from layman Christians.

Theodorus of Tabennese, also known as Abba Theodorus and Theodore the Sanctified was the spiritual successor to Pachomius and played a crucial role in preventing the first Christian cenobitic monastic federation from collapsing after the death of its founder.

Monasticism is a way of life where a person lives outside of society, under religious vows.

Chariton the Confessor was an early Christian monk. He is venerated as a saint by both the Western and Eastern Churches. His remembrance day is September 28.

Desert Mothers is a neologism, coined in feminist theology as an analogy to Desert Fathers, for the ammas or female Christian ascetics living in the desert of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria in the 4th and 5th centuries AD. They typically lived in the monastic communities that began forming during that time, though sometimes they lived as hermits. Monastic communities acted collectively with limited outside relations with lay people. Some ascetics chose to venture into isolated locations to restrict relations with others, deepen spiritual connection, and other ascetic purposes. Other women from that era who influenced the early ascetic or monastic tradition while living outside the desert are also described as Desert Mothers.

Pbow was a cenobitic monastery established by St. Pachomius in 336-337 AD. Pbow is about 100 km (62 mi) north of Luxor in modern Upper Egypt.

Tbew was an Egyptian Coptic Orthodox monastery that was established in the mid fourth-century.