Viracocha is the great creator deity in the pre-Inca and Inca mythology in the Andes region of South America. According to the myth Viracocha had human appearance and was generally considered as bearded. According to the myth he ordered the construction of Tiwanaku. It is also said that he was accompanied by men also referred to as Viracochas.

Tiwanaku is a Pre-Columbian archaeological site in western Bolivia, near Lake Titicaca, about 70 kilometers from La Paz, and it is one of the largest sites in South America. Surface remains currently cover around 4 square kilometers and include decorated ceramics, monumental structures, and megalithic blocks. In AD 800 the site has been conservatively estimated to have been inhabited by 10,000 to 20,000 people.

In "Southern Andean Iconographic Series" the Staff God pose is a religious icon and a standardized pose reminiscent in its way of the standardized poses in Byzantine art. The pose shows a front-facing human or human-like figure with vertical attributes, one in each hand. There is no uniform representation of a "Staff God". Dozens of variations of "Staff Gods" exist. Some scholars think that some of these personages are possible depictions of Viracocha or Thunupa. However, there is little evidence to support the idea that these front-facing figures do represent deities. Some researchers point to their attributes and spatial organization which seem to indicate that they are ritual practitioners. Some attributes in their hands were identified as Qirus, Snuff trays and Spear-throwers. The "rays" radiating or sprouting out of the faces of Tiwanaku front-facing figures appear to have approximately the value of an aureole. They may represent flows and distribution of energy. At the Wari site of Conchopata a vessel was found which shows a Staff God in which the "rays" can be interpreted as a Anadenanthera colubrina tree sprouting from its head whereas the circular elements do represent its seed pods.

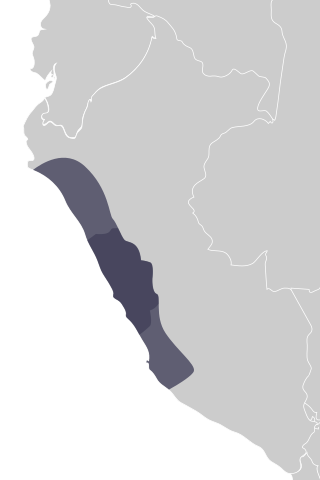

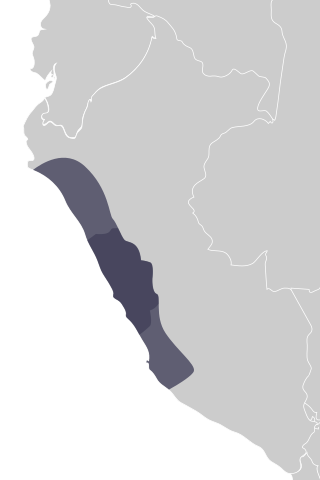

The Wari were a Middle Horizon civilization that flourished in the south-central Andes and coastal area of modern-day Peru, from about 500 to 1000 AD.

The Chavín culture is an extinct, pre-Columbian civilization, developed in the northern Andean highlands of Peru around 900 BCE, ending around 250 BCE. It extended its influence to other civilizations along the Peruvian coast. The Chavín people were located in the Mosna Valley where the Mosna and Huachecsa rivers merge. This area is 3,150 metres (10,330 ft) above sea level and encompasses the quechua, suni, and puna life zones. In the periodization of pre-Columbian Peru, the Chavín is the main culture of the Early Horizon period in highland Peru, characterized by the intensification of the religious cult, the appearance of ceramics closely related to the ceremonial centers, the improvement of agricultural techniques and the development of metallurgy and textiles.

Ollantaytambo is a town and an Inca archaeological site in southern Peru some 72 km (45 mi) by road northwest of the city of Cusco. It is located at an altitude of 2,792 m (9,160 ft) above sea level in the district of Ollantaytambo, province of Urubamba, Cusco region. During the Inca Empire, Ollantaytambo was the royal estate of Emperor Pachacuti, who conquered the region, and built the town and a ceremonial center. At the time of the Spanish conquest of Peru, it served as a stronghold for Manco Inca Yupanqui, leader of the Inca resistance. Located in the Sacred Valley of the Incas, it is now an important tourist attraction on account of its Inca ruins and its location en route to one of the most common starting points for the four-day, three-night hike known as the Inca Trail.

The Lanzón is a granite stela that is associated with the Chavín culture. It is located in the Old Temple of Chavin de Huantar which rests in the central highlands of Peru. The Chavín religion was the first major religious and cultural movement in the Andes mountains, flourishing between 900 and 200 BCE. The Lanzón itself was erected during the Early Horizon period of Andean art circa 500 BCE and takes its name from the Spanish word for "lance," an allusion to the shape of the sculpture. The name is deceiving, as its form more closely resembles a highland plow which would have been used for agricultural purposes at the time. It is suspected because of this that the deity depicted is linked to agrarian worship.

Pre-Columbian art refers to the visual arts of indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, North, Central, and South Americas from at least 13,000 BCE to the European conquests starting in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. The Pre-Columbian era continued for a time after these in many places, or had a transitional phase afterwards. Many types of perishable artifacts that were once very common, such as woven textiles, typically have not been preserved, but Precolumbian monumental sculpture, metalwork in gold, pottery, and painting on ceramics, walls, and rocks have survived more frequently.

Inca architecture is the most significant pre-Columbian architecture in South America. The Incas inherited an architectural legacy from Tiwanaku, founded in the 2nd century B.C.E. in present-day Bolivia. A core characteristic of the architectural style was to use the topography and existing materials of the land as part of the design. The capital of the Inca empire, Cuzco, still contains many fine examples of Inca architecture, although many walls of Inca masonry have been incorporated into Spanish Colonial structures. The famous royal estate of Machu Picchu is a surviving example of Inca architecture. Other significant sites include Sacsayhuamán and Ollantaytambo. The Incas also developed an extensive road system spanning most of the western length of the continent and placed their distinctive architecture along the way, thereby visually asserting their imperial rule along the frontier.

The Raimondi Stele is a sacred object and significant piece of art of the Chavín culture of the central Andes in present-day Peru. The Chavín were named after Chavín de Huantar, the main structure found in ruin at this archaeological site. The Chavín are believed to have occupied this space from 1500 BCE to 300 BCE, which places them in the Early Horizon period of Andean cultures. The Early Horizon came to rise after the spread and domination of Chavín art styles, namely the hanging pendant eye and anthropomorphism/zoomorphism of feline, serpent, and crocodilian creatures. The stele is seven feet high, made of highly polished granite, with a lightly incised design featuring these key artistic choices shown in the depiction of the Staff God. After not being found in situ, the stele now is housed in the courtyard of the Museo Nacional de Arqueología Antropología e Historia del Perú in Lima.

Julio César Tello Rojas was a Peruvian archaeologist. Tello is considered the "father of Peruvian archeology" and was the first indigenous archaeologist in South America.

The Gate of the Sun, also known as the Gateway of the Sun (in older literature simply called " monolithic Gateway of Ak-kapana", is a monolithic gateway at the site of Tiahuanaco by the Tiwanaku culture, an Andean civilization of Bolivia that thrived around Lake Titicaca in the Andes of western South America around 500-950 AD.

Pumapunku or Puma Punku is a 6th-century T-shaped and strategically aligned man-made terraced platform mound with a sunken court and monumental structure on top that is part of the Pumapunku complex, at the Tiwanaku Site near Tiwanacu, in western Bolivia. The Pumapunku complex is an alignment of plazas and ramps centered on the Pumapunku platform mound. Today the monumental complex on top of the platform mound lies in ruins.

The Andean civilizations were South American complex societies of many indigenous people. They stretched down the spine of the Andes for 4,000 km (2,500 mi) from southern Colombia, to Ecuador and Peru, including the deserts of coastal Peru, to north Chile and northwest Argentina. Archaeologists believe that Andean civilizations first developed on the narrow coastal plain of the Pacific Ocean. The Caral or Norte Chico civilization of coastal Peru is the oldest known civilization in the Americas, dating back to 3500 BCE. Andean civilization is one of the six "pristine" civilizations of the world, created independently and without influence by other civilizations.

The history of human habitation in the Andean region of South America stretches from circa 15,000 BCE to the present day. Stretching for 7,000 km (4,300 mi) long, the region encompasses mountainous, tropical and desert environments. This colonisation and habitation of the region has been affected by its unique geography and climate, leading to the development of unique cultural and socn.

The Kotosh Religious Tradition is a term used by archaeologists to refer to the ritual buildings that were constructed in the mountain drainages of the Andes between circa 3000 and c. 1800 BCE, during the Andean preceramic, or Late Archaic period of Andean history.

The Recuay culture was a pre-Columbian culture of highland Peru that flourished from 200 BCE to 600 CE and was related to the Moche culture of the north coast. It is named after the Recuay District, in the Recuay Province, in the Ancash Region of Peru.

The Tiwanaku Polity was a Pre-Columbian polity in western Bolivia based in the southern Lake Titicaca Basin. Tiwanaku was one of the most significant Andean civilizations. Its influence extended into present-day Peru and Chile and lasted from around 600 to 1000 AD. Its capital was the monumental city of Tiwanaku, located at the center of the polity's core area in the southern Lake Titicaca Basin. This area has clear evidence for large-scale agricultural production on raised fields that probably supported the urban population of the capital. Researchers debate whether these fields were administered by a bureaucratic state (top-down) or through a federation of communities with local autonomy. Tiwanaku was once thought to be an expansive military empire, based mostly on comparisons to the later Inca Empire. However, recent research suggests that labelling Tiwanaku as an empire or even a state may be misleading. Tiwanaku is missing a number of features traditionally used to define archaic states and empires: there is no defensive architecture at any Tiwanaku site or changes in weapon technology, there are no princely burials or other evidence of a ruling dynasty or a formal social hierarchy, no evidence of state-maintained roads or outposts, and no markets.

Richard Lewis Burger, Ph.D., is an archaeologist and anthropologist from the United States. He is currently a professor at Yale University and holds the positions of Charles J. MacCurdy Professor in the Anthropology Department, Chair of the Council on Archaeological Studies, and Curator in the Division of Anthropology at the Peabody Museum of Natural History. He has carried out archaeological excavations in the Peruvian Andes since 1975, publishing several books and many articles on Chavin culture, a pre-Hispanic civilization that developed in the northern Andean highlands of Peru from 1000 BC to 400 BC. Burger is married to Lucy Salazar, a Peruvian archaeologist and long time collaborator on many research projects. His former doctoral student Sabine Hyland has become well-known as an Andean anthropologist.

A snuff tray, also known as a snuff tablet, is a hand-carved tablet or tray that was made for the purpose of inhaling a psychoactive drug (also referred to as being hallucinogenic, entheogenic, or psychedelic, in the form similar to tobacco snuff prepared as a powder using a snuff tube. Snuff trays are best-known from the Tiwanaku culture of the Andes in South America. The principal substance thought to have been inhaled was known as willka, also referred to as cebil, and known as yopó in northern South America and cohoba in the Greater Antilles, where it was also prepared from other species of the genus Anadenanthera.