The Maritimes, also called the Maritime provinces, is a region of Eastern Canada consisting of three provinces: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. The Maritimes had a population of 1,899,324 in 2021, which makes up 5.1% of Canada's population. Together with Canada's easternmost province, Newfoundland and Labrador, the Maritime provinces make up the region of Atlantic Canada.

Nova Scotia is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland."

Citadel Hill is a hill that is a National Historic Site in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. Four fortifications have been constructed on Citadel Hill since the city was founded by the English in 1749, and were referred to as Fort George—but only the third fort was officially named Fort George. According to General Orders of October 20, 1798, it was named after King George III. The first two and the fourth and current fort, were officially called the Halifax Citadel. The last is a concrete star fort.

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestown, Virginia, and more substantially with the founding of the Thirteen Colonies along the Atlantic coast of North America.

The Canadian–American Reciprocity Treaty of 1854, also known as the Elgin–Marcy Treaty, was a treaty between the United Kingdom and the United States that applied to British North America, including the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland Colony. The treaty covered raw materials; in effect from 1854 to 1866, it represented a move toward free trade and was opposed by protectionist elements in the United States.

The Intercolonial Railway of Canada, also referred to as the Intercolonial Railway (ICR), was a historic Canadian railway that operated from 1872 to 1918, when it became part of Canadian National Railways. As the railway was also completely owned and controlled by the Government of Canada, the Intercolonial was also one of Canada's first Crown corporations.

At the time of the American Civil War (1861–1865), Canada did not yet exist as a federated nation. Instead, British North America consisted of the Province of Canada and the separate colonies of Newfoundland, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, British Columbia and Vancouver Island, as well as a crown territory administered by the Hudson's Bay Company called Rupert's Land. Britain and its colonies were officially neutral for the duration of the war. Despite this, tensions between Britain and the United States were high due to incidents such as the Trent Affair, blockade runners loaded with British arms supplies bound for the Confederacy, and the Confederate Navy commissioning of the CSS Alabama from Britain.

Maritime Union is a proposed political union of the three Maritime provinces of Canada – New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island – to form a single new province. This vision has sometimes been expanded to a proposed Atlantic Union, which would also include the province of Newfoundland and Labrador.

William Johnston Almon was a Nova Scotian physician and Canadian parliamentarian. He was the son of William Bruce Almon.

Sir Charles Hastings Doyle was a British military officer who was the second Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia post Confederation and the first Lieutenant Governor of New Brunswick.

The community of Halifax, Nova Scotia was created on 1 April 1996, when the City of Dartmouth, the City of Halifax, the Town of Bedford, and the County of Halifax amalgamated and formed the Halifax Regional Municipality. The former City of Halifax was dissolved, and transformed into the Community of Halifax within the municipality.

Starting with the 1763 Treaty of Paris, New France, of which the colony of Canada was a part, formally became a part of the British Empire. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 enlarged the colony of Canada under the name of the Province of Quebec, which with the Constitutional Act 1791 became known as the Canadas. With the Act of Union 1840, Upper and Lower Canada were joined to become the United Province of Canada.

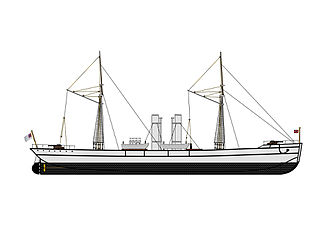

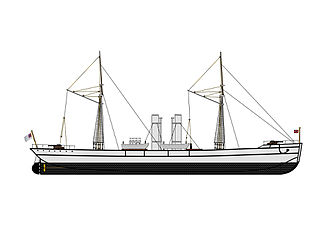

The CSS Tallahassee was a twin-screw steamer and cruiser in the Confederate States Navy, purchased in 1864, and used for commerce raiding off the Atlantic coast. She later operated under the names CSS Olustee and CSS Chameleon.

Sambro is a rural fishing community on the Chebucto Peninsula in the Halifax Regional Municipality, in Nova Scotia, Canada.

The history of Nova Scotia covers a period from thousands of years ago to the present day. Prior to European colonization, the lands encompassing present-day Nova Scotia were inhabited by the Mi'kmaq people. During the first 150 years of European settlement, the region was claimed by France and a colony formed, primarily made up of Catholic Acadians and Mi'kmaq. This time period involved six wars in which the Mi'kmaq along with the French and some Acadians resisted the British invasion of the region: the French and First Nation Wars, Father Rale's War and Father Le Loutre's War. During Father Le Loutre's War, the capital was moved from Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, to the newly established Halifax, Nova Scotia (1749). The warfare ended with the Burying the Hatchet ceremony (1761). After the colonial wars, New England Planters and Foreign Protestants immigrated to Nova Scotia. After the American Revolution, Loyalists immigrated to the colony. During the nineteenth century, Nova Scotia became self-governing in 1848 and joined the Canadian Confederation in 1867.

The Naval Museum of Halifax is a Canadian Forces museum located at CFB Halifax in the former official residence of the Commander-in-Chief of the North America Station (1819–1905). Also known as the "Admiralty House", the residence is a National Historic Site of Canada located in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. The museum collects, preserves and displays the artifacts and history of the Royal Canadian Navy.

Nova Scotia is a Canadian province located in Canada's Maritimes. The region was initially occupied by Mi'kmaq. The colonial history of Nova Scotia includes the present-day Maritime Provinces and the northern part of Maine, all of which were at one time part of Nova Scotia. In 1763, Cape Breton Island and St. John's Island became part of Nova Scotia. In 1769, St. John's Island became a separate colony. Nova Scotia included present-day New Brunswick until that province was established in 1784. During the first 150 years of European settlement, the colony was primarily made up of Catholic Acadians, Maliseet, and Mi'kmaq. During the last 75 years of this time period, there were six colonial wars that took place in Nova Scotia. After agreeing to several peace treaties, the long period of warfare ended with the Halifax Treaties (1761) and two years later, when the British defeated the French in North America (1763). During those wars, the Acadians, Mi'kmaq and Maliseet from the region fought to protect the border of Acadia from New England. They fought the war on two fronts: the southern border of Acadia, which New France defined as the Kennebec River in southern Maine, and in Nova Scotia, which involved preventing New Englanders from taking the capital of Acadia, Port Royal and establishing themselves at Canso.

The Royal Navy Burying Ground is part of the Naval Museum of Halifax and was the Naval Hospital cemetery for the North America and West Indies Station at Halifax, Nova Scotia. It is the oldest military burial ground in Canada. The cemetery has grave markers to those who died while serving at Halifax and were treated at the Naval medical facility or died at sea. Often shipmates and officers had the grave markers erected to mark the deaths of the crew members who died while in the port of Halifax.

Lieutenant Charles Carroll Wood was the first Canadian Officer to die in the Second Boer War. As a member of a family that had distinguished itself in America, his great grandfather being Zachary Taylor, 12th President of the United States, he was buried with full military honours.

Section 145 of the Constitution Act, 1867 is a repealed provision of the Constitution of Canada which required the federal government to build a railway connecting the River St. Lawrence with Halifax, Nova Scotia.