This article has an unclear citation style .(July 2011) |

The Chester Mystery Plays is a cycle of mystery plays originating in the city of Chester, England and dating back to at least the early part of the 15th century. [1]

This article has an unclear citation style .(July 2011) |

The Chester Mystery Plays is a cycle of mystery plays originating in the city of Chester, England and dating back to at least the early part of the 15th century. [1]

Biblical dramas were being performed in Latin across continental Europe as early as the 10th century dramatizing the events surrounding the birth of Christ. Later, priests of Benediktbeuern Abbey in Bavaria combined costumes and content from the Old Testament with their Christmas plays. [2]

By the late 12th century, biblical plays were performed outside of churches and were written in vernacular languages. They still emphasized incidents of the Old and New Testaments but were more dramatic and less strict about following biblical accounts. The 1150 AD performance titled The Play of Adam from Norman France dramatized the fall of Adam in the garden of Eden. [2]

The inclusion of drama was extremely popular among the French population and found similar popularity in England. In the 14th century, vernacular Bible dramas were performed across England for three main reasons: the introduction of the Feast of Corpus Christi, the growing population of towns and municipal governments independent of feudal lords, and the development of trade guilds. [2]

Pope Urban IV created the Feast of Corpus Christi in 1264 to celebrate the literal presence of Christ within the bread and wine of the Catholic Eucharist. The feast occurred on Trinity Sunday between May and June, and priests processed through the streets displaying the “Host” of Jesus which was a consecrated wafer encased within a casket. [3]

The urbanization of townships resulted in populations becoming increasingly dependent on each other, enabling the specialization of labor. There were trade guilds for bakers, tailors, and goldsmiths who trained apprentices and regulated wages and working conditions. These skilled laborers working with their local communities helped build the stages and props for the performances. Subsequently, the staging of these dramatic performances became increasingly urban and informed from continental Europe by constant trade crossing the channel into England. [4]

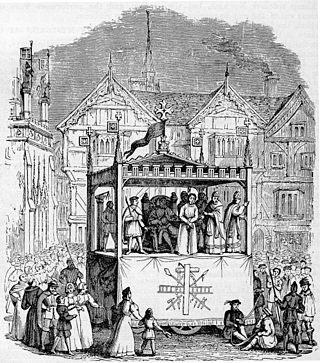

The “Host” would be accompanied by a tableau of biblical scenes which represented sacred Christian history which is the origin of the cycle plays. By 1394, biblical plays were being performed in York, England. The usage of pageant wagons enabled performances to travel across the country to various communities throughout England. The plays attracted people to the towns, and communities benefited from the commercial trade. [2]

The Mystery plays were banned nationally in the 16th century. Chester was the last to concede in 1578 and so became the longest-running cycle in medieval times. It was revived in 1951 for the Festival of Britain, and they have since been staged every five years. [5]

Prior to the performance, the Crier (officer) read out these banns: "The Aldermen and stewards of every society and company draw yourselves to your said several companies according to Ancient Custom and so to appear with your said several Companies every man as you are Called upon pain that shall fall thereon". Such early banns exhorted each company to perform well.

Under Queen Elizabeth I, the plays were seen as "Popery" and banned by the Church of England. Despite this, a play cycle was performed in 1568 and the cathedral paid for the stage and beer as in 1562. They were performed in 1572 despite a protest by a minister. [6]

One edition of the plays begins with "The Banes which are reade beefore the beginninge of the playes of Chester, 4 June 1600". Each play ends with "Finis. Deo gracias! per me Georgi Bellin. 1592". [7]

The plays were revived in Chester in 1951 as part of the Festival of Britain and are presented there every five years. [8]

The Players of St Peter have been performing the plays in London roughly every five years since 1946. [9]

Under the direction of Jeff Dailey, the American Theatre of Actors in New York City performed the penultimate play, The Coming of Antichrist, in August 2017. [10]

In the twentieth century, the Noah's Flood play was set operatically by both Benjamin Britten ( Noye's Fludde ) and Igor Stravinsky ( The Flood ). The play regarded the relationship between wife and husband (urban life) and spoke about the physical and spiritual world that provides a backdrop of the play. Britten also set the Abraham and Isaac play as Canticle II: Abraham and Isaac .

The Mysteries is an adaption by poet Tony Harrison, principally based upon the Wakefield Cycle, but incorporating scenes from the York, Chester, and N-Town canons. It was first performed in 1977 at the National Theatre and revived in 2000 as a celebration of the millennium.

Mystery plays and miracle plays are among the earliest formally developed plays in medieval Europe. Medieval mystery plays focused on the representation of Bible stories in churches as tableaux with accompanying antiphonal song. They told of subjects such as the Creation, Adam and Eve, the murder of Abel, and the Last Judgment. Often they were performed together in cycles which could last for days. The name derives from mystery used in its sense of miracle, but an occasionally quoted derivation is from ministerium, meaning craft, and so the 'mysteries' or plays performed by the craft guilds.

The Passion Play or Easter pageant is a dramatic presentation depicting the Passion of Jesus Christ: his trial, suffering and death. The viewing of and participation in Passion Plays is a traditional part of Lent in several Christian denominations, particularly in the Catholic and Evangelical traditions; as such Passion Plays are often ecumenical Christian productions.

The N-Town Plays are a cycle of 42 medieval Mystery plays from between 1450 and 1500.

A kontakion is a form of hymn in the Byzantine liturgical tradition.

Chester's Midsummer Watch Parade is a festival celebrated in Chester, England.

Noye's Fludde is a one-act opera by the British composer Benjamin Britten, intended primarily for amateur performers, particularly children. First performed on 18 June 1958 at that year's Aldeburgh Festival, it is based on the 15th-century Chester "mystery" or "miracle" play which recounts the Old Testament story of Noah's Ark. Britten specified that the opera should be staged in churches or large halls, not in a theatre.

Christian drama or Christian tragedy is based on Christian religious themes.

Medieval theatre encompasses theatrical in the period between the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century and the beginning of the Renaissance in approximately the 15th century. The category of "medieval theatre" is vast, covering dramatic performance in Europe over a thousand-year period. A broad spectrum of genres needs to be considered, including mystery plays, morality plays, farces and masques. The themes were almost always religious. The most famous examples are the English cycle dramas, the York Mystery Plays, the Chester Mystery Plays, the Wakefield Mystery Plays, and the N-Town Plays, as well as the morality play known as Everyman. One of the first surviving secular plays in English is The Interlude of the Student and the Girl.

The Wakefield or Towneley Mystery Plays are a series of thirty-two mystery plays based on the Bible most likely performed around the Feast of Corpus Christi probably in the town of Wakefield, England during the Late Middle Ages until 1576. It is one of only four surviving English mystery play cycles. Some scholars argue that the Wakefield cycle is not a cycle at all, but a mid-sixteenth-century compilation, formed by a scribe bringing together three separate groups of plays.

The York Mystery Plays, more properly the York Corpus Christi Plays, are a Middle English cycle of 48 mystery plays or pageants covering sacred history from the creation to the Last Judgment. They were traditionally presented on the feast day of Corpus Christi and were performed in the city of York, from the mid-fourteenth century until their suppression in 1569. The plays are one of four virtually complete surviving English mystery play cycles, along with the Chester Mystery Plays, the Towneley/Wakefield plays and the N-Town plays. Two long, composite, and late mystery pageants have survived from the Coventry cycle and there are records and fragments from other similar productions that took place elsewhere. A manuscript of the plays, probably dating from between 1463 and 1477, is still intact and stored at the British Library.

PLS, or Poculi Ludique Societas, the Medieval & Renaissance Players of Toronto, sponsors productions of early plays, from the beginnings of medieval drama to as late as the middle of the seventeenth century.

Robert Mayer Lumiansky (1913–1987) was an American scholar of Medieval English and president of the American Council of Learned Societies.

The Brome play of Abraham and Isaac is a fifteenth-century play of unknown authorship, written in an East Anglian dialect of Middle English, which dramatises the story of the Akedah, the binding of Isaac.

The Digby Conversion of Saint Paul is a Middle English miracle play of the late fifteenth century. Written in rhyme royal, it is about the conversion of Paul the Apostle. It is part of a collection of mystery plays that was bequeathed to the Bodleian Library by Sir Kenelm Digby in 1634.

A pageant wagon is a movable stage or wagon used to accommodate the mystery and miracle play cycles of the 10th through the 16th century. These religious plays were developed from biblical texts; at the height of their popularity, they were allowed to stay within the churches, and special stages were erected for them.

The Macro Manuscript is a collection of three 15th-century English morality plays, known as the "Macro plays" or "Macro moralities": Mankind, The Castle of Perseverance, and Wisdom. So named for its 18th-century owner Reverend Cox Macro (1683–1767), the manuscript contains the earliest complete examples of English morality plays. A stage plan attached to The Castle of Perseverance is also the earliest known staging diagram in England. The manuscript is the only source for The Castle of Perseverance and Mankind and the only complete source for Wisdom. The Macro Manuscript is a part of the collection at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C.. For centuries, scholars have studied the Macro Manuscript for insights into medieval drama. As Clifford Davidson writes in Visualizing the Moral Life, "in spite of the fact that the plays in the manuscript are neither written by a single scribe nor even attributed to a single date, they collectively provide our most important source for understanding the fifteenth century English morality play."

Peter Meredith was, prior to retirement, a lecturer in medieval and early modern English language and literature. He was editor of the journal Leeds Studies in English from around 1978 to 1981 and chaired its editorial board from 1985 until his retirement. He was also an editor of Medieval English Theatre. He is particularly noted for his contributions, through editing, research, and performance, to the study of medieval English theatre.

Passion Plays in the United Kingdom have had a long and complex history involving faith and devotion, civic pageantry, antisemitism, religious and political censorship, large-scale revival and historical re-enactments. The origin and history of Passion Play in the UK differs substantially from Passion Plays in Europe, South and North America, Australia and other parts of the world.

Canticle IV: The Journey of the Magi, Op. 86, is a composition for three male solo voices and piano by Benjamin Britten, part of his series of five Canticles. It sets the text of T. S. Eliot's poem "Journey of the Magi", retelling the story of the biblical Magi. The work was premiered in June 1971 at the Aldeburgh Festival by James Bowman, Peter Pears and John Shirley-Quirk, with Britten as the pianist. It was published the following year, dedicated to the three singers.

Canticle II: Abraham and Isaac, Op. 51, is a composition for tenor, alto and piano by Benjamin Britten, part of his series of five Canticles. Commissioned to be performed as a fundraiser for the English Opera Group, it sets the story of Abraham and Isaac from the Chester Mystery Plays. Britten assigned the tenor voice of Peter Pears to Abraham, the alto of Kathleen Ferrier to Isaac, and both singers singing in homophony to the voice of God. The work was premiered on 20 January 1952 by Pears and Ferrier, with Britten as the pianist. It was published by Boosey & Hawkes in 1952, dedicated to the singers.