Arachnida is a class of joint-legged invertebrate animals (arthropods), in the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, harvestmen, camel spiders, whip spiders and vinegaroons.

Ricinulei is a small order of arachnids. Like most arachnids, they are predatory, eating small arthropods. They occur today in west-central Africa (Ricinoides) and the Americas as far north as Texas. As of 2021, 91 extant species of ricinuleids have been described worldwide, all in the single family Ricinoididae. In older works they are sometimes referred to as Podogona. Due to their obscurity they do not have a proper common name, though in academic literature they are occasionally referred to as hooded tickspiders.

The family Dipluridae, known as curtain-web spiders are a group of spiders in the infraorder Mygalomorphae, that have two pairs of booklungs, and chelicerae (fangs) that move up and down in a stabbing motion. A number of genera, including that of the Sydney funnel-web spider (Atrax), used to be classified in this family but have now been moved to Atracidae.

The Mesothelae are a suborder of spiders that includes a single extant family, Liphistiidae, and a number of extinct families. This suborder is thought to form the sister group to all other living spiders, and to retain ancestral characters, such as a segmented abdomen with spinnerets in the middle and two pairs of book lungs. Members of Liphistiidae are medium to large spiders with eight eyes grouped on a tubercle. They are found only in China, Japan, and southeast Asia. The oldest known Mesothelae spiders are known from the Carboniferous, over 300 million years ago.

The spider family Liphistiidae, recognized by Tamerlan Thorell in 1869, comprises 8 genera and about 100 species of medium-sized spiders from Southeast Asia, China, and Japan. They are among the most basal living spiders, belonging to the suborder Mesothelae. In Japan, the Kimura spider is well known.

Araneida is a subgroup of Tetrapulmonata. It was originally defined by Jörg Wunderlich in 2015 as a subgroup of Araneae, including all true spiders, with Wunderlich also including Uraraneida within Araneae. Araneida was redefined by Wunderlich in 2019 to include all modern spiders (Araneae), as well as Chimerarachnida, but excluding Uraraneida. Chimerarachnida and Araneae both possess spinnerets, which are absent in Uraraneida. Uraraneida and Araneida are grouped together in the clade Serikodiastida.

The evolution of spiders has been ongoing for at least 380 million years. The group's origins lie within an arachnid sub-group defined by the presence of book lungs ; the arachnids as a whole evolved from aquatic chelicerate ancestors. More than 45,000 extant species have been described, organised taxonomically in 3,958 genera and 114 families. There may be more than 120,000 species. Fossil diversity rates make up a larger proportion than extant diversity would suggest with 1,593 arachnid species described out of 1,952 recognized chelicerates. Both extant and fossil species are described annually by researchers in the field. Major developments in spider evolution include the development of spinnerets and silk secretion.

The anatomy of spiders includes many characteristics shared with other arachnids. These characteristics include bodies divided into two tagmata, eight jointed legs, no wings or antennae, the presence of chelicerae and pedipalps, simple eyes, and an exoskeleton, which is periodically shed.

This glossary describes the terms used in formal descriptions of spiders; where applicable these terms are used in describing other arachnids.

Garcorops jadis is a possibly extinct species of Wall crab spider, family Selenopidae, and at present, it is one of four known species in the genus Garcorops. The species is solely known from copal found on the beach near Sambava, on the northeast coast of Madagascar.

Mongolarachne is an extinct genus of spiders placed in the monogeneric family Mongolarachnidae. The genus contains only one species, Mongolarachne jurassica, described in 2013, which is presently the largest fossilized spider on record. The type species was originally described as Nephila jurassica and placed in the living genus Nephila which contains the golden silk orb-weavers.

Uraraneida is an extinct order of Paleozoic arachnids related to modern spiders. Two genera of fossils have been definitively placed in this order: Attercopus from the Devonian of United States and Permarachne from the Permian of Russia. Like spiders, they are known to have produced silk, but lack the characteristic spinnerets of modern spiders, and retain elongate telsons.

Brasilionata is a genus of Brazilian spiders first described by Wunderlich in 1995. It is represented by a single species, B. arborense. The defining characteristics of this genus include a homogeneous color pattern on the back of the abdomen, setae on the cymbial fold the same size as other setae, a space between the anterior median eyes, and a pointed switch on the end of the palpal bulb similar to that of Microdipoena. Only two specimens have been identified, one in 1995 and another in 2015.

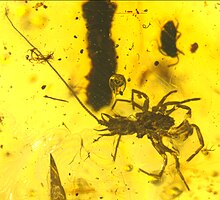

Burmesarchaea is a diverse extinct genus of spiders, placed in the family Archaeidae. The type species Burmesarchaea grimaldii was first described in 2003 and least 13 more species have been assigned to the genus. The genus has been exclusively found in Cretaceous Burmese amber, which is dated to 99 million years ago.

Avicularioidea is a clade of mygalomorph spiders, one of the two main clades into which mygalomorphs are divided. It has been treated at the rank of superfamily.

Priscaleclercera is a genus of araneomorph spiders in the family Psilodercidae, containing seven species. The genus was first described by Jorge Wunderlich in 2017, and its fossils have been found in Burmese amber, while live specimens have been found in Indonesia (Sulawesi).

Burmese amber is fossil resin dating to the early Late Cretaceous Cenomanian age recovered from deposits in the Hukawng Valley of northern Myanmar. It is known for being one of the most diverse Cretaceous age amber paleobiotas, containing rich arthropod fossils, along with uncommon vertebrate fossils and even rare marine inclusions. A mostly complete list of all taxa described up until 2018 can be found in Ross 2018; its supplement Ross 2019b covers most of 2019.

Fossilcalcaridae is an extinct Mygalomorphae spider family in the clade Avicularioidea containing the single species Fossilcalcar praeteritus. The family genus and species were described in 2015 from a male fossil entombed in Cretaceous age Burmese amber.

Lagonomegopidae is an extinct family of spiders known from the Cretaceous period. Members of the family are distinguished by a large pair of eyes, positioned on the anterolateral flanks of the carapace, with the rest of the eyes being small. They have generally been considered members of Palpimanoidea, but this has recently been questioned. Members of the family are known from the late Early Cretaceous (Albian) to near the end of the Late Cretaceous (Campanian) of Eurasia, North America and the Middle East, which was then attached to Africa as part of Gondwana. They are generally assumed to have been free living hunters as opposed to web builders.

Jörg Wunderlich is a German arachnologist and palaeontologist. He is best known for his study of spiders in amber, describing over 1000 species, 300 genera, 50 tribes/subfamilies and 18 families in over 180 publications. Unlike most other arachnologists Jörg has never held any academic position and has worked as a private individual with no financial support for travel or equipment.