CESNUR, is a non-profit organization based in Turin, Italy that studies new religious movements and opposes the anti-cult movement. It was established in 1988 by Massimo Introvigne, Jean-François Mayer and Ernesto Zucchini. Its first president was Giuseppe Casale. Later, Luigi Berzano became CESNUR's president.

Massimo Introvigne is an Italian Roman Catholic sociologist of religion and intellectual property attorney. He is a founder and the managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), a Turin-based organization which has been described as "the highest profile lobbying and information group for controversial religions".

Alleanza Cattolica, at the beginning Foedus Catholicum, is an Italian Catholic association. Among its members are Massimo Introvigne, president of CESNUR.

Martino Martini, born and raised in Trento, was a Jesuit missionary. As cartographer and historian, he mainly worked on ancient Imperial China.

Mario Perniola was an Italian philosopher, professor of aesthetics and author. Many of his works have been published in English.

Donatella della Porta is an Italian sociologist and political scientist, who is Professor of political science and political sociology at the Scuola Normale Superiore. She is known for her research in the areas of social movements, corruption, political violence, police and policies of public order. In 2022, she was named a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Alberto Melloni is an Italian church historian and a Unesco Chairholder of the Chair on Religious Pluralism & Peace, primarily known for his work on the Councils and the Second Vatican Council. Since 2020, he is one of the European Commission's Chief Scientific Advisors.

The UCOII is one of the main Italian Islamic association.

Wenzhou people or Wenzhounese people is a subgroup of Oujiang Wu Chinese speaking peoples, who live primarily in Wenzhou, Zhejiang province. Wenzhou people are known for their business and money-making skills. The area also has a large diaspora population in Europe and the United States, with a reputation for being enterprising natives who start restaurants, retail and wholesale businesses in their adopted countries. About two-thirds of the overseas community is in Europe. Wenzhounese people have also made notable contributions to mathematics and technology.

Alberto Ronchey was an Italian journalist, essayist and politician.

In 2000 Paolo Brescia and Tommaso Principi established the collective OBR to investigate new ways of contemporary living, creating a design network among Milan, London and New York. After working with Renzo Piano, Paolo and Tommaso have oriented the research of OBR towards the integration artifice-nature, to create sensitive architecture in perpetual change, stimulating the interaction between man and environment. The team of OBR develops its design activity through public-private social programs, promoting – through architecture – the sense of community and the individual identities. Today OBR is group open to different multidisciplinary contributors, cooperating with different universities, such as Accademia di Architettura di Mendrisio, Aalto University, Academy of Architecture of Mumbai and Mimar Sinan Fine Art University. Among the best known works by OBR are the Pythagoras Museum, the New Galleria Sabauda in Turin, the Milanofiori Residential Complex, the Children Hospital in Parma, the Galliera Hospital in Genoa, the Lido of Genoa, the Ex Cinema Roma, the Triennale di Milano Terrace. The under construction projects by OBR include the Lehariya Cluster in Jaipur, the Jafza Traders Market in Dubai and the Multiuse Complex Ahmad Qasir in Teheran. OBR's projects have been featured in Venice Biennale of Architecture, Royal Institute of British Architects in London, Bienal de Arquitetura of Brasilia, MAXXI in Rome and Triennale di Milano. OBR has been awarded with the AR Award for Emerging Architecture at RIBA, the Plusform under 40, the Urbanpromo at the 11° Biennale di Venezia, the honourable mention for the Medaglia d'Oro all'Architettura Italiana, the Europe 40 Under 40 in Madrid, the Leaf Award overall winner in London, the WAN Residential Award, the Building Healthcare Award, the Inarch Award for Italian Architecture and the American Architecture Prize in New York. Since 2004 OBR has been evolving its design parameters according to the environmental and energy certification LEED and since 2009 OBR is partner of the GBC.

Pietro Trifone, is an Italian linguist.

Luigi Berzano is an Italian sociologist and Catholic priest.

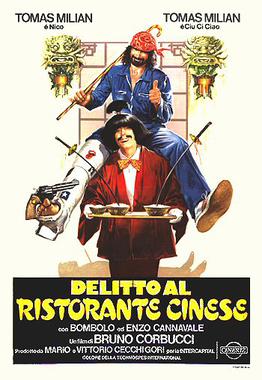

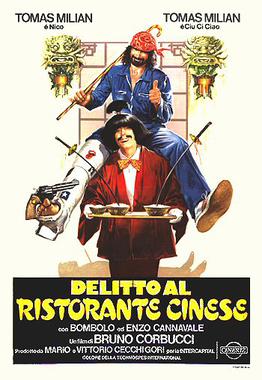

Crime at the Chinese Restaurant is a 1981 Italian "poliziottesco"-comedy film directed by Bruno Corbucci. It is the eighth chapter in the Nico Giraldi film series; in this chapter Tomas Milian plays a double role, the inspector Nico Giraldi and the Chinese Ciu Ci Ciao, a character reprised, with slight changes, from the role of Sakura that the same Milian played in the 1975 spaghetti western The White, the Yellow, and the Black.

Paolo Brescia is an Italian architect and founder of OBR Open Building Research. He graduated with a degree in architecture from the Politecnico di Milano in 1996 and had his academic fellowship at Architectural Association in London. After working with Renzo Piano, he founded in 2000 OBR with Tommaso Principi to investigate new ways of contemporary living, creating a design network among Milan, London, Mumbai and New York. He combines his professional experience with the academic world as guest lecturer in several athenaeums, such as Accademia di Architettura di Mendrisio, Kent State University, Aalto University, University of Oulu, Academy of Architecture of Mumbai, College of Architecture of Pune, Mimar Sinan Fine Art University, Hacettepe University, Florida International University in Miami. He was university professor in charge at Politecnico di Milano (2004-2005) and University of Genoa (2013-2015). With OBR his projects have been featured in international exhibitions, including at X Biennale di Architettura in Venice 2006; RIBA Royal Institute of British Architects in London 2007; V Bienal de Arquitetura in Brasilia 2007; XI Bienal Internacional de Arquitectura in Buenos Aires 2007; AR Award Exhibition in Berlin 2008; China International Architectural Expo in Beijing 2009; International Expo in Shangai 2010; UIA 24th World Congress of Architecture in Tokyo 2011; Energy at MAXXI in Rome 2013; Italy Now in Bogotá 2014; Small Utopias in Johannesburg 2014; XIV Biennale di Architettura in Venice 2014; Triennale di Milano in Milan 2015 and Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in New York 2016.

Furio Jesi was an Italian historian, writer, archaeologist, and philosopher.

The Taoist Church of Italy is a religious body of Taoism established in 2013 by Vincenzo di Ieso, a fourteenth-generation Taoist master of the Xuanwu school of the Wudang Mountains, into which he was initiated in 1993 with the ecclesiastical name of Li Xuanzong. Despite the founder's particular affiliation, the church intends to incorporate all forms of Taoism in Italy. The establishment of the church has been defined by a scholar of religious rights as a "crucial event for both Taoism and religious freedom in Italy".

Natalino Fossati is a former Italian professional footballer and manager who played as a full-back.

Massimo Mila was an Italian musicologist, music critic, intellectual and anti-fascist.

Joseph Hager was an Austrian linguist, lexicographer, orientalist, writer and academic naturalized Italian.