The Eleventh Amendment is an amendment to the United States Constitution which was passed by Congress on March 4, 1794, and ratified by the states on February 7, 1795. The Eleventh Amendment restricts the ability of individuals to bring suit against states of which they are not citizens in federal court.

Hollingsworth v. Virginia, 3 U.S. 378 (1798), was a case in which the United States Supreme Court ruled early in America's history that the President of the United States has no formal role in the process of amending the United States Constitution and that the Eleventh Amendment was binding on cases already pending prior to its ratification.

The Judiciary Act of 1789 was a United States federal statute enacted on September 24, 1789, during the first session of the First United States Congress. It established the federal judiciary of the United States. Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution prescribed that the "judicial power of the United States, shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and such inferior Courts" as Congress saw fit to establish. It made no provision for the composition or procedures of any of the courts, leaving this to Congress to decide.

Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908), is a United States Supreme Court case that allows suits in federal courts for injunctions against officials acting on behalf of states of the union to proceed despite the State's sovereign immunity, when the State acted contrary to any federal law or contrary to the Constitution.

Hans v. Louisiana, 134 U.S. 1 (1890), was a decision of the United States Supreme Court determining that the Eleventh Amendment prohibits a citizen of a U.S. state to sue that state in a federal court. Citizens cannot bring suits against their own state for cases related to the federal constitution and federal laws. The court left open the question of whether a citizen may sue his or her state in state courts. That ambiguity was resolved in Alden v. Maine (1999), in which the Court held that a state's sovereign immunity forecloses suits against a state government in state court.

Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974), was a United States Supreme Court case that held that the sovereign immunity recognized in the Eleventh Amendment prevented a federal court from ordering a state from paying back funds that had been unconstitutionally withheld from parties to whom they had been due.

Seminole Tribe of Florida v. Florida, 517 U.S. 44 (1996), was a United States Supreme Court case which held that Article One of the U.S. Constitution did not give the United States Congress the power to abrogate the sovereign immunity of the states that is further protected under the Eleventh Amendment. Such abrogation is permitted where it is necessary to enforce the rights of citizens guaranteed under the Fourteenth Amendment as per Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer. The case also held that the doctrine of Ex parte Young, which allows state officials to be sued in their official capacity for prospective injunctive relief, was inapplicable under these circumstances, because any remedy was limited to the one that Congress had provided.

Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376 U.S. 398 (1964), was a United States Supreme Court case that determined that the policy of United States federal courts would be to honor the Act of State Doctrine, which dictates that the propriety of decisions of other countries relating to their internal affairs would not be questioned in the courts of the United States.

Northern Insurance Company of New York v. Chatham County, 547 U.S. 189 (2006), is a United States Supreme Court case addressing whether state counties enjoyed sovereign immunity from private lawsuits authorized by federal law. The case involved an admiralty claim by an insurer against Chatham County, Georgia for its negligent operation of a drawbridge. The Court ruled unanimously that the county had no basis for claiming immunity because it was not acting as an "arm of the state."

Kimel v. Florida Board of Regents, 528 U.S. 62 (2000), was a US Supreme Court case that determined that the US Congress's enforcement powers under the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution did not extend to the abrogation of state sovereign immunity under the Eleventh Amendment over complaints of discrimination that is rationally based on age.

Nevada Department of Human Resources v. Hibbs, 538 U.S. 721 (2003), was a United States Supreme Court case which held that the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 was "narrowly targeted" at "sex-based overgeneralization" and was thus a "valid exercise of [congressional] power under Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment."

This is a list of cases reported in volume 2 U.S. of United States Reports, decided by the Supreme Court of the United States from 1791 to 1793. Case reports from other federal and state tribunals also appear in 2 U.S..

The Jay Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1789 to 1795, when John Jay served as the first Chief Justice of the United States. Jay served as Chief Justice until his resignation, at which point John Rutledge took office as a recess appointment. The Supreme Court was established in Article III of the United States Constitution, but the workings of the federal court system were largely laid out by the Judiciary Act of 1789, which established a six-member Supreme Court, composed of one Chief Justice and five Associate Justices. As the first President, George Washington was responsible for appointing the entire Supreme Court. The act also created thirteen judicial districts, along with district courts and circuit courts for each district.

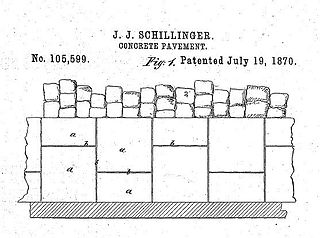

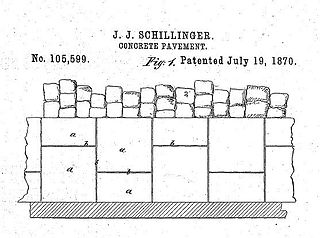

Schillinger v. United States, 155 U.S. 163 (1894), is a decision of the United States Supreme Court, holding that a suit for patent infringement cannot be entertained against the United States, because patent infringement is a tort and the United States has not waived sovereign immunity for intentional torts.

James Iredell was one of the first Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was appointed by President George Washington and served from 1790 until his death in 1799. His son, James Iredell Jr., was a Governor of North Carolina.

In United States law, the federal government as well as state and tribal governments generally enjoy sovereign immunity, also known as governmental immunity, from lawsuits. Local governments in most jurisdictions enjoy immunity from some forms of suit, particularly in tort. The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act provides foreign governments, including state-owned companies, with a related form of immunity—state immunity—that shields them from lawsuits except in relation to certain actions relating to commercial activity in the United States. The principle of sovereign immunity in US law was inherited from the English common law legal maxim rex non potest peccare, meaning "the king can do no wrong." In some situations, sovereign immunity may be waived by law.

Bank of the United States v. Deveaux, 9 US 61 (1809) is an early US corporate law case decided by the US Supreme Court. It held that corporations have the capacity to sue in federal court on grounds of diversity under article three, section two of the United States Constitution. It was the first Supreme Court case to examine corporate rights and, while it is rarely featured prominently in US legal history, it set an important precedent for the legal rights of corporations, particularly with regard to corporate personhood.

The Copyright Remedy Clarification Act (CRCA) is a United States copyright law that attempted to abrogate sovereign immunity of states for copyright infringement. The CRCA amended 17 USC 511(a):

In general. Any State, any instrumentality of a State, and any officer or employee of a State or instrumentality of a State acting in his or her official capacity, shall not be immune, under the Eleventh Amendment of the Constitution of the United States or under any other doctrine of sovereign immunity, from suit in Federal Court by any person, including any governmental or nongovernmental entity, for a violation of any of the exclusive rights of a copyright owner provided by sections 106 through 122, for importing copies of phonorecords in violation of section 602, or for any other violation under this title.

OBB Personenverkehr AG v. Sachs, 577 U.S. ___ (2015), is a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States, holding that the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act barred a California resident from bringing suit against an Austrian railroad in federal district court. The case arose after a California resident suffered traumatic personal injuries while attempting to board a train in Innsbruck, Austria. She then filed a lawsuit against the railroad in the United States District Court for the Northern District of California in which she alleged the railroad was responsible for causing her injuries. Because the railroad was owned by the Austrian government, the railroad claimed that the lawsuit should be barred by the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, which provides immunity to foreign sovereigns in tort suits filed in the United States. In response, the plaintiff argued that her suit should be permitted under the Foreign Sovereign Immunity Act's commercial activity exception because she purchased her rail ticket in the United States.

Franchise Tax Board of California v. Hyatt, 587 U.S. ___ (2019), was a United States Supreme Court case that determined that unless they consent, states have sovereign immunity from private suits filed against them in the courts of another state. The 5–4 decision overturned precedent set in a 1979 Supreme Court case, Nevada v. Hall. This was the third time that the litigants had presented their case to the Court, as the Court had already ruled on the issue in 2003 and 2016.