The Church in Scotland was Reformed under the guidance of John Knox and other Reformers. The King took over the lands of abbeys and bishoprics, turning many into lordships for his supporters, or giving some of them to universities or town councils. The lands associated with supporting parish clergy – or ministers, as they were now called – were generally undisturbed. The king took over the role of default patron, in the absence of any specific patron. The First Book of Discipline (1560) and the Second Book of Discipline (1578) laid down the rules for the reformed Church of Scotland. Both stipulated that ministers should be chosen by congregations. The First Book never became civil law, and neither did the part of the Second Book relating to patronage, as the right of the heirs of original donors to nominate suitable clerics to a parish was called.

However, by an Act of the Parliament of Scotland (1567) presentation by laick (lay) patronages was expressly preserved, the patron being bound to present a qualified person within six months of vacancy occurring. By the same act, an appeal against the presented candidate by the congregation could only be on the basis of the qualifications of the presentee.

By the "Golden Act" of 1592, which established Presbyterianism as the only legal form of Church government in Scotland, Presbyteries were "bound and astricted to receive and admit whatsoever qualified minister is presented be (sic) his Majesty or laic patron". If a congregation refused to accept a suitable nominee, the Patron was entitled to enjoy the fruits of the original bequest - stipend, lands, house, etc. [3]

By the beginning of the 17th century, Patronage was well established in custom and law. A Patron could be the King, one of the Universities, a Town or Burgh Council or a landowner, such as the Duke of Argyle (who had nine patronages). [4]

Patronage Act 1711

Patronage was a much less disputed issue in the Anglican Church, and the dispossessed Scottish lay patrons were able to persuade the united, and mainly Anglican, Parliament of Great Britain that they had unjustly lost a purely civil right. Their case may have been strengthened by the fact that Article 20 of the Treaty of Union had preserved all heritable rights and jurisdictions of pre-Union Scotland. It also helped that the British Government distrusted popular participation in matters of importance, as the selection of parish ministers certainly was. Consequently, the Church Patronage (Scotland) Act 1711 was passed, restoring to their original owners the right to present suitably qualified candidates to Presbyteries in the event of a vacancy. Only those Patron's who had renounced their claim in writing in return for compensation were excluded from this, of which there were only three in 1711, Cadder, Old and New Monklands. [7] The effect was the restoration of the situation as it was in 1592. Patrons were required to swear allegiance to the Hanoverian kings, and abjure the claims of the Stuart Pretenders; a patron who refused was to appoint commissioners to exercise the patronage on his behalf. [8] Patrons did not need to be members of the Church of Scotland.

The Act came into force on 1 May 1712.

Disputes

Moderates acquiesce reluctantly

The Church of Scotland mainly acquiesced in this restoration, though it felt aggrieved and the General Assembly protested to Parliament almost every year that it was contrary to the Treaty of Union. [9] The congregation of a Parish could only legally object to a presentee on the grounds of his suitability, so the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland laid down increasingly stringent educational, moral and practical qualifications for candidates for the ministry. Moreover, few patrons dared to suggest scandalously unqualified candidates.

Appointments were, however, regularly contested through the church courts - Kirk Session, Presbytery and Synod finally to be decided at the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. As most objections were on the acceptability of the candidate, rather than his suitability, the Assembly usually decided in favour of the Patron, particularly as he could seek civil damages in the Court of Session otherwise.

The civil courts were involved because disputes related to the stipends and property of Parishes, to ownership of the property of the right to Patronage, who had the right to exercise it and whether time limits had been breached.

Eventually, as most ministers owed their appointment to a patron, they were unwilling to challenge the system. Many were also wary of more democratic involvement in Church governance. The status of the Church itself had been guaranteed by Act of Parliament, so it tended towards supporting legal procedures, though it protested against them. Many patrons were wary of provoking disputes, so tried to work with the heritors and elders of their parishes to present candidates who met with General Assembly criteria in terms of education, character and practical ability. This group of ministers, heritors, elders and patrons – called Moderates - formed the dominant group in the Church of Scotland during the 18th century.

Evangelicals oppose on principle

Other Ministers, Heritors and Elders objected to Patronage on principle, as compromising the independence of the Church and the right of congregations freely to call their own Ministers. They viewed the whole of the 17th century as a struggle to achieve this, most notably during the Covenanter disturbances, culminating in the victory of the Glorious Revolution. Later, this Party of principled opposition was called the Evangelicals. It became dominant in the 19th century. Moreover, the buying and selling of church offices - Simony - was against Church law. When a Patron tried to sell his right (or, more normally, when this was advertised as part of the sale of an estate), the cry of Simony was raised. As no money passed to Ministers or from Ministers to Patrons, this charge had moral force, but no legal effect, either in Church or civil courts. Discontented Parishioners had many options open to them at every level of Church and Civil courts to question the suitability of a candidate, on educational, moral, or practical grounds, but more normally on the firmness of his attachment to the Westminster Confession of Faith. They could also query the right of a particular Patron, or his Commissioner, or the timing, or formal wording of a particular presentation, or whether formal Church processes had been properly carried out.

In addition to formal, legal opposition, many disputed appointments were occasions for popular demonstrations of discontent, sometimes linked to political demands for more democracy. Presbyteries were empowered to call in the army to impose a disputed appointment.

Outcome

The Act was highly opposed by the Church of Scotland because of its intrusion into church elections and was considered lay investiture. The General Assembly of 1712, inserted a clause in the instructions to its Commissioners to protest to Parliament and this instruction was repeated annually until 1784. [10] However, due to the strength of the aristocracy, the Act remained in force for a considerable length of time. It was finally repealed by section 3 of the Church Patronage (Scotland) Act 1874 (c. 82).

Eighteenth-century legislation

An act of Parliament, 1719, required any presentee to declare his willingness to take up his patron's offer, to prevent a patron from presenting a candidate whom he knew would not take up a post, in order to profit himself from the stipend. Many optimistically thought this was the end of patronage, as no right-thinking Presbyterian would declare willingness to accept a patron's offer, but after an uncertain few years, patronage continued as the norm. [11]

1730 General Assembly

An Act by the General Assembly of 1730, by which objectors to decisions of Church courts could no longer have these objections officially recorded, was regarded by Evangelicals as a move to silence their opposition to Patronage.

1732 General Assembly

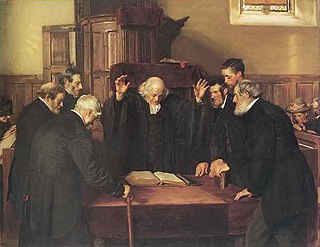

When a Patron failed to nominate a candidate for a vacancy within six months, his right of Patronage fell to the Presbytery. Each Presbytery proceeded as it saw fit, but the General Assembly of 1732 passed an Act which regulated this, by establishing the 1690 rules, granting the Patronage right to the Heritors and Elders, with procedures to be followed if a congregation objected to a candidate. Some members, including Ebenezer Erskine wanted to see the regulations of 1649 applied, by which all heads of families in a congregation called a Minister. The fact that they could no longer have their objections recorded led to the first schism in the Church of Scotland - the Original Secession.

Veto Act

The General Assembly of 1834 enacted the Veto Act, which prohibited the installation of a patron-presented minister in a congregation if the heads of a majority of member households objected to him and gave their reasons to the presbytery. [12] This event marked the end of the dominance of the Moderates and showed the strength of the Evangelicals.

Great Disruption 1843

A series of civil actions in the period 1838 - 1841 in the Court of Session, and confirmed in the House of Lords declared the above Veto Act ultra vires, so it was unenforceable by law. They also indicated that the Church of Scotland, having been set up by statute, was subject to the law of the land in all civil matters. Its Presbyteries were liable to severe financial penalties if they resisted Patron's nominees using the Veto Act. Court orders were made forbidding the ordination of Ministers who might harm the interests of a Patron's nominee. [13] This led to the Great Disruption of 1843 - a walk-out of about 40% of the Ministers, led by Thomas Chalmers - and the setting up of the Free Church of Scotland. This Church at the time had no doctrinal or theological difference with the majority of Ministers who remained in the Church of Scotland, but it contained the greater proportion of evangelical ministers. Those who remained within the Church of Scotland were determined to remain within the law, and in 1874 they secured abolition of the Patronage Act.

Abolition

By the Church Patronage (Scotland) Act 1874, 163 years after the 1711 Act, lay patronage was abolished for the Church of Scotland, thus enabling presbyteries to follow canon law in the choice of ministers. Initially, ministers were chosen by a meeting of all the heads of households and elders, but a sophisticated process of trials was then developed, which by the second half of the twentieth century, also allowed women a voice in the selection of ministers. The General Assembly introduced the innovation of deaconesses in 1898, created the concept of women elders in 1966, and the concept of women ministers in 1968.

Presbyterianpolity is a method of church governance typified by the rule of assemblies of presbyters, or elders. Each local church is governed by a body of elected elders usually called the session or consistory, though other terms, such as church board, may apply. Groups of local churches are governed by a higher assembly of elders known as the presbytery or classis; presbyteries can be grouped into a synod, and presbyteries and synods nationwide often join together in a general assembly. Responsibility for conduct of church services is reserved to an ordained minister or pastor known as a teaching elder, or a minister of the word and sacrament.

The Church of Scotland is the national church in Scotland, and one of the country's largest, with over 270,000 members. According to the government Scottish Household Survey in 2019, 20% of the Scottish population identified the Church of Scotland as their religious identity. The Church of Scotland's governing system is presbyterian in its approach, therefore, no one individual or group within the church has more or less influence over church matters. There is no one person who acts as the head of faith, as the church believes that role is the "Lord God's".

William Carstares was a minister of the Church of Scotland, active in Whig politics.

The Church of Scotland Act 1921 is an Act of the British Parliament. The purpose of the Act was to settle centuries of dispute between the British Parliament and the Church of Scotland over the Church's independence in spiritual matters. The passing of the Act saw the British Parliament recognise the Church's independence in spiritual matters, by giving legal recognition to the Articles Declaratory.

George Gillespie was a Scottish theologian.

The Disruption of 1843, also known as the Great Disruption, was a schism in 1843 in which 450 evangelical ministers broke away from the Church of Scotland to form the Free Church of Scotland. The main conflict was over whether the Church of Scotland or the British Government had the power to control clerical positions and benefits. The Disruption came at the end of a bitter conflict within the Church of Scotland, and had major effects in the church and upon Scottish civic life.

The General Assembly of the Church of Scotland is the sovereign and highest court of the Church of Scotland, and is thus the Church's governing body. It generally meets each year and is chaired by a Moderator elected at the start of the Assembly.

A Church of Scotland congregation is led by its minister and elders. Both of these terms are also used in other Christian denominations: see Minister (Christianity) and Elder (Christianity). This article discusses the specific understanding of their roles and functions in the Scottish Church.

James Meek FRSE (1742–1810) was Minister of Cambuslang from 1774 until his death. He was Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1795, but is most remembered as the model Enlightenment cleric who wrote the entry for Cambuslang in the First Statistical Account of Scotland.

William M'Culloch was Minister of Cambuslang during the extraordinary events of the Cambuslang Work (1742) when 30,000 people gathered in the hillsides near his church for preaching and communion. Many were there struck by their own depravity and horrified at the probable punishment after death. Trembling, wailing, great pain, nose-bleeding and other strange behaviour was followed in some cases by striking conversions when they suddenly felt accepted by Christ. This gave rise to great rejoicing and singing. It was later calculated that about 400 people had been converted, though many had backslided. The Reverend M’Culloch was a strange person to be at the centre of this phenomenon — one that was being repeated in the American Colonies at the time. He was a poor preacher and claimed never to have experienced the strong feelings of sin or conversion that so many others had reported.

The First Secession was an exodus of ministers and members from the Church of Scotland in 1733. Those who took part formed the Associate Presbytery and later the United Secession Church. They were often referred to as Seceders.

Robert Arnot (1744–1808) was a Scottish Presbyterian minister and professor of divinity in St Andrews University, who was Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1794.

Archibald Davidson was a Scottish minister who was moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1788 and was principal of Glasgow University.

Robert Liston was a Scottish minister who served as Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1787/88.

The Church Patronage (Scotland) Act 1874 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It repealed the Church Patronage (Scotland) Act 1711. It was passed on 7 August 1874 and its long title is An Act to alter and amend the laws relating to the Appointment of Ministers to Parishes in Scotland.

Neil Campbell was a Scottish Minister, Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland at the start of the Original Secession and Principal of Glasgow University during a flourishing period of the Scottish Enlightenment.

The Glorious Revolution in Scotland refers to the Scottish element of the 1688 Glorious Revolution, in which James VII was replaced by his daughter Mary II and her husband William II as joint monarchs of Scotland and England. Prior to 1707, the two kingdoms shared a common monarch but were separate legal entities, so decisions in one did not bind the other. In both countries, the Revolution confirmed the primacy of Parliament over the Crown, while the Church of Scotland was re-established as a Presbyterian rather than Episcopalian polity.

Scottish religion in the eighteenth century includes all forms of religious organisation and belief in Scotland in the eighteenth century. This period saw the beginnings of a fragmentation of the Church of Scotland that had been created in the Reformation and established on a fully Presbyterian basis after the Glorious Revolution. These fractures were prompted by issues of government and patronage, but reflected a wider division between the Evangelicals and the Moderate Party. The legal right of lay patrons to present clergymen of their choice to local ecclesiastical livings led to minor schisms from the church. The first in 1733, known as the First Secession and headed by figures including Ebenezer Erskine, led to the creation of a series of secessionist churches. The second in 1761 led to the foundation of the independent Relief Church.

In the Scottish church of the 18th and 19th centuries, a burgher was a person who upheld the lawfulness of the burgess oath.

William Wilson was born in Glasgow, on 9 November 1690. He was the son of Gilbert Wilson, proprietor of a small estate near East Kilbride.. William Wilson's mother was Isabella, daughter of Ramsay of Shielhill. William was named after William of Orange and was educated at University of Glasgow, graduating with an M.A. in 1707. He was licensed by the Presbytery of Dunfermline on 23 September 1713 and called unanimously on 21 August 1716. He was ordained on 1st November 1716. He had a call to Rhynd, but was continued by the Presbytery in Perth. Associating with the supporters of the Marrow of Modern Divinity, he with three others Ebenezer Erskine, Alexander Moncrieff, and James Fisher laid the foundation of the Secession Church, for which they were suspended by the Commission of Assembly 9 August, and declared no longer ministers of the Church 12 November 1733. He was deposed by the Assembly 15 May 1740. He and his people erected a meeting-house, and the Associate Presbytery appointed him their Professor of Divinity, 5 November 1736, but he sank under his contentions and labours and died 8 October 1741. He is said to have combined "the excellencies of both Erskines, with excellencies peculiar to himself."