Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance. It also includes the right not to profess any religion or belief or "not to practise a religion".

A chapel is a Christian place of prayer and worship that is usually relatively small. The term has several meanings. First, smaller spaces inside a church that have their own altar are often called chapels; the Lady chapel is a common type of these. Second, a chapel is a place of worship, sometimes non-denominational, that is part of a building, complex, or vessel with some other main purpose, such as a school, college, hospital, palace or large aristocratic house, castle, barracks, prison, funeral home, cemetery, airport, or a military or commercial ship. Third, chapels are small places of worship, built as satellite sites by a church or monastery, for example in remote areas; these are often called a chapel of ease. A feature of all these types is that often no clergy were permanently resident or specifically attached to the chapel.

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". Historically, most incidents and writings pertaining to toleration involve the status of minority and dissenting viewpoints in relation to a dominant state religion. However, religion is also sociological, and the practice of toleration has always had a political aspect as well.

Toleration is when one allows, permits, or accepts an action, idea, object, or person that one dislikes or disagrees with.

The Stadttempel, also called the Seitenstettengasse Temple, is the main synagogue of Vienna, Austria. It is located in the Innere Stadt 1st district, at Seitenstettengasse 4.

The Patent of Toleration was an edict of toleration issued on 13 October 1781 by the Habsburg emperor Joseph II. Part of the Josephinist reforms, the Patent extended religious freedom to non-Catholic Christians living in the crown lands of the Habsburg monarchy, including Lutherans, Calvinists, and the Eastern Orthodox. Specifically, these members of minority faiths were now legally permitted to hold "private religious exercises" in clandestine churches.

The Reformed Church of France was the main Protestant denomination in France with a Calvinist orientation that could be traced back directly to John Calvin. In 2013, the Church merged with the Evangelical Lutheran Church in France to form the United Protestant Church of France.

The Italian Synagogue is one of five synagogues in the Venetian Ghetto of Venice.

The Spanish Synagogue is one of the two functioning synagogues in the Venetian Ghetto of Venice, northern Italy. It is open for services from Passover until the end of the High Holiday season.

Traenheim is a commune in the Bas-Rhin department in Grand Est in north-eastern France.

A shared church, simultaneum mixtum, a term first coined in 16th-century Germany, is a church in which public worship is conducted by adherents of two or more religious groups. Such churches became common in the German-speaking lands of Europe in the wake of the Protestant Reformation. The different Christian denominations, share the same church building, although they worship at different times and with different clergy. It is thus a form of religious toleration.

Atheism, as defined by the entry in Diderot and d'Alembert's Encyclopédie, is "the opinion of those who deny the existence of a God in the world. The simple ignorance of God doesn't constitute atheism. To be charged with the odious title of atheism one must have the notion of God and reject it." In the period of the Enlightenment, avowed and open atheism was made possible by the advance of religious toleration, but was also far from encouraged.

Benjamin Jacob Kaplan is a historian and professor of Dutch history at University College London and the University of Amsterdam.

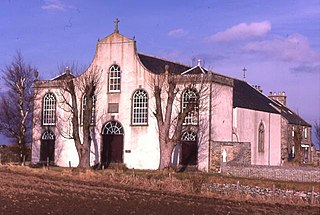

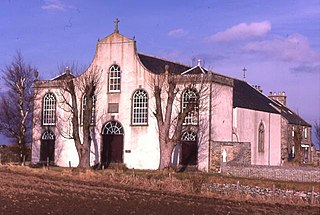

St Ninian's Church, Tynet is a historic Roman Catholic clandestine church located at Tynet about 4 miles to the west of Buckie, Scotland in the Enzie region. Erected in 1755, it is the oldest surviving Roman Catholic church built in Scotland after the Reformation.

St. Gregory's Church is a Roman Catholic church at Preshome near Buckie in north-east Scotland. It is protected as a category A listed building.

Vrijburg is an historic clandestine church concealed behind a row of houses fronting on the Keizersgracht, Amsterdam. It is situated in the center of the block, with houses on all four sides and no frontage on any public street.

Félix Le Pelletier de la Houssaye was a French statesman who became Controller-General of Finances.

The Sardinian Embassy Chapel was an important Catholic church and embassy chapel attached to the Embassy of the Kingdom of Sardinia in the Lincoln's Inn area of London. It was demolished in 1909.

An embassy chapel is a place of worship within a foreign mission. Historically they have sometimes acted as clandestine churches, tolerated by the authorities to operate discreetly. Since embassies are exempt from the host country's laws, a form of extraterritoriality, these chapels were able to provide services to prohibited and persecuted religious groups. For example, Catholic embassy chapels in Great Britain provided services while Catholicism was banned under the Penal Laws. A similar role was filled for Protestants by the Prussian embassy chapel in Rome, where Protestantism was unlawful until 1871. Upon laws granting freedom of religion, these embassy chapels have often become regularized churches and parishes, such as that of the Dutch embassy chapel to the Ottoman Empire, now The Union Church of Istanbul.