Balance of trade can be measured in terms of commercial balance, or net exports. Balance of trade is the difference between the monetary value of a nation's exports and imports over a certain time period. Sometimes a distinction is made between a balance of trade for goods versus one for services. The balance of trade measures a flow variable of exports and imports over a given period of time. The notion of the balance of trade does not mean that exports and imports are "in balance" with each other.

Mercantilism is a nationalist economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports for an economy. In other words, it seeks to maximize the accumulation of resources within the country and use those resources for one-sided trade.

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and policy that taxes foreign products to encourage or safeguard domestic industry. Protective tariffs are among the most widely used instruments of protectionism, along with import quotas and export quotas and other non-tariff barriers to trade.

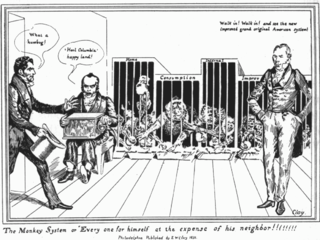

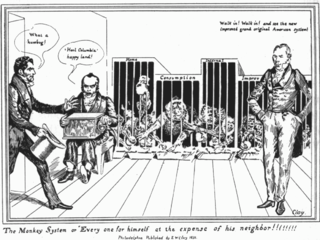

The Tariff Act of 1890, commonly called the McKinley Tariff, was an act of the United States Congress, framed by then Representative William McKinley, that became law on October 1, 1890. The tariff raised the average duty on imports to almost 50%, an increase designed to protect domestic industries and workers from foreign competition, as promised in the Republican platform. It represented protectionism, a policy supported by Republicans and denounced by Democrats. It was a major topic of fierce debate in the 1890 Congressional elections, which gave a Democratic landslide.

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold economically liberal positions, while economic nationalist and left-wing political parties generally support protectionism, the opposite of free trade.

Jean-Baptiste Colbert was a French statesman who served as First Minister of State from 1661 until his death in 1683 under the rule of King Louis XIV. His lasting impact on the organization of the country's politics and markets, known as Colbertism, a doctrine often characterized as a variant of mercantilism, earned him the nickname le Grand Colbert.

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. Proponents argue that protectionist policies shield the producers, businesses, and workers of the import-competing sector in the country from foreign competitors and raise government revenue. Opponents argue that protectionist policies reduce trade, and adversely affect consumers in general as well as the producers and workers in export sectors, both in the country implementing protectionist policies and in the countries against which the protections are implemented.

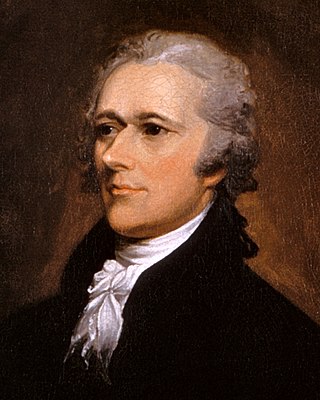

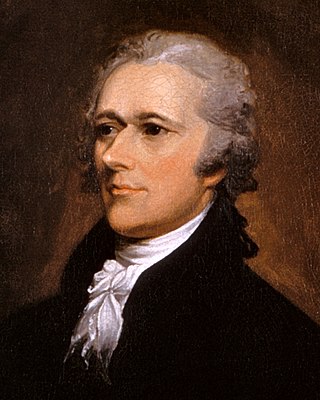

The American School, also known as the National System, represents three different yet related constructs in politics, policy and philosophy. The policy existed from the 1790s to the 1970s, waxing and waning in actual degrees and details of implementation. Historian Michael Lind describes it as a coherent applied economic philosophy with logical and conceptual relationships with other economic ideas.

Dirigisme or dirigism is an economic doctrine in which the state plays a strong directive (policies) role, contrary to a merely regulatory interventionist role, over a market economy. As an economic doctrine, dirigisme is the opposite of laissez-faire, stressing a positive role for state intervention in curbing productive inefficiencies and market failures. Dirigiste policies often include indicative planning, state-directed investment, and the use of market instruments to incentivize market entities to fulfill state economic objectives.

Economic nationalism is an ideology that prioritizes state intervention in the economy, including policies like domestic control and the use of tariffs and restrictions on labor, goods, and capital movement. The core belief of economic nationalism is that the economy should serve nationalist goals. As a prominent modern ideology, economic nationalism stands in contrast to economic liberalism and economic socialism.

The economic history of France involves major events and trends, including the elaboration and extension of the seigneurial economic system in the medieval Kingdom of France, the development of the French colonial empire in the early modern period, the wide-ranging reforms of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Era, the competition with the United Kingdom and other neighboring states during industrialization and the extension of imperialism, the total wars of the late-19th and early 20th centuries, and the introduction of the welfare state and integration with the European Union since World War II.

The infant industry argument is an economic rationale for trade protectionism. The core of the argument is that nascent industries often do not have the economies of scale that their older competitors from other countries may have, and thus need to be protected until they can attain similar economies of scale. The logic underpinning the argument is that trade protectionism is costly in the short run but leads to long-term benefits.

Imperial Preference was a system of mutual tariff reduction enacted throughout the British Empire as well as the then British Commonwealth following the Ottawa Conference of 1932. As Commonwealth Preference, the proposal was later revived in regard to the members of the Commonwealth of Nations. Joseph Chamberlain, the powerful colonial secretary from 1895 until 1903, argued vigorously that Britain could compete with its growing industrial rivals and thus maintain Great Power status. The best way to do so would be to enhance internal trade inside the worldwide British Empire, with emphasis on the more developed areas — Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa — that had attracted large numbers of British settlers.

The Bourbon Reforms consisted of political and economic changes promulgated by the Spanish Crown under various kings of the House of Bourbon, since 1700, mainly in the 18th century. The beginning of the new Crown's power with clear lines of authority to officials contrasted to the complex system of government that evolved under the Habsburg monarchs. For example, the crown pursued state predominance over the Catholic Church, pushed economic reforms, and placed power solely into the hands of civil officials.

Tariffs have historically served a key role in the trade policy of the United States. Their purpose was to generate revenue for the federal government and to allow for import substitution industrialization by acting as a protective barrier around infant industries. They also aimed to reduce the trade deficit and the pressure of foreign competition. Tariffs were one of the pillars of the American System that allowed the rapid development and industrialization of the United States. The United States pursued a protectionist policy from the beginning of the 19th century until the middle of the 20th century. Between 1861 and 1933, they had one of the highest average tariff rates on manufactured imports in the world. However American agricultural and industrial goods were cheaper than rival products and the tariff had an impact primarily on wool products. After 1942 the U.S. began to promote worldwide free trade, but after the 2016 presidential election has gone back to protectionism.

The Eden Treaty was a treaty signed between Great Britain and France in 1786, named after the British negotiator William Eden, 1st Baron Auckland (1744–1814). The French side was represented by Joseph Matthias Gérard de Rayneval. It effectively ended, for a brief time, the economic war between France and Great Britain and set up a system to reduce tariffs on goods from either country. It was spurred on in Britain by the secession of the thirteen American colonies, and the publication of Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations. British Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger was heavily influenced by the ideas of Smith, and was one of the key motivators of the treaty.

The American System was an economic plan that played an important role in American policy during the first half of the 19th century, rooted in the "American School" ideas of Alexander Hamilton.

Economic liberalism is a political and economic ideology that supports a market economy based on individualism and private property in the means of production. Adam Smith is considered one of the primary initial writers on economic liberalism, and his writing is generally regarded as representing the economic expression of 19th-century liberalism up until the Great Depression and rise of Keynesianism in the 20th century. Historically, economic liberalism arose in response to feudalism and mercantilism.

Protectionism in the United States is protectionist economic policy that erects tariffs and other barriers on imported goods. In the US this policy was most prevalent in the 19th century. At that time it was mainly used to protect Northern industries and was opposed by Southern states that wanted free trade to expand cotton and other agricultural exports. Protectionist measures included tariffs and quotas on imported goods, along with subsidies and other means, to restrain the free movement of imported goods, thus encouraging local industry.

Protective tariffs are tariffs that are enacted with the aim of protecting a domestic industry. They aim to make imported goods cost more than equivalent goods produced domestically, thereby causing sales of domestically produced goods to rise, supporting local industry. Tariffs are also imposed in order to raise government revenue, or to reduce an undesirable activity. Although a tariff can simultaneously protect domestic industry and earn government revenue, the goals of protection and revenue maximization suggest different tariff rates, entailing a tradeoff between the two aims.